Causes of congenital neutropenia and challenges of diagnosis

The congenital neutropenia syndromes are rare conditions caused by mutations in genes associated with various cell processes. While their clinical presentations may overlap, their natural histories vary. Accurate diagnosis of the genetic etiology of specific conditions is crucial for providing individually tailored management, as the different syndromes have different risk profiles for progression to bone marrow failure and leukemia. However, before molecular diagnostic studies are pursued, the diagnosis of a congenital neutropenia must generally be considered. CLI chatted to Dr Xenia Parisi (Hematopathology Fellow, Department of Hematopathology, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, Texas, USA) to find out more about how the diagnosis of these conditions requires clinical suspicion.

Could start by giving us some basic definitions, please?

Neutrophils, or polymorphonuclear cells (PMNs), are granular leukocytes with tissue-homing capacity that serve as a critical effector cell of the innate immune system. Neutrophils degranulate to entrap and destroy invading microbes. They phagocytose and digest pathogens, along with remnant debris of infection. They furthermore play a central role in mediating chemokine/cytokine responses to microorganisms.

Neutropenia describes the lower-than-normal absolute neutrophil counts (ANC) in the peripheral blood, typically below 1500 cells/µL. Because of the neutrophil’s central role in mediating infection responses, a patient’s risk for infection correlates inversely with their ANC. Profound neutropenia (ANC below 500 cells/µL) carries a high associated risk for mortality despite optimal clinical management.

Neutropenia in general is a clinical sign and can be classed as primary or secondary/acquired. Secondary neutropenia can occur in completely healthy people as the result of a variety of reasons: certain types of infections, medications, a poor nutritional status, the physiological changes of pregnancy, immune-related disorders or hematological malignancy. These neutropenias are quite common clinically, and it is important to identify and manage, but they are usually transient, resolving with treatment of the underlying condition.

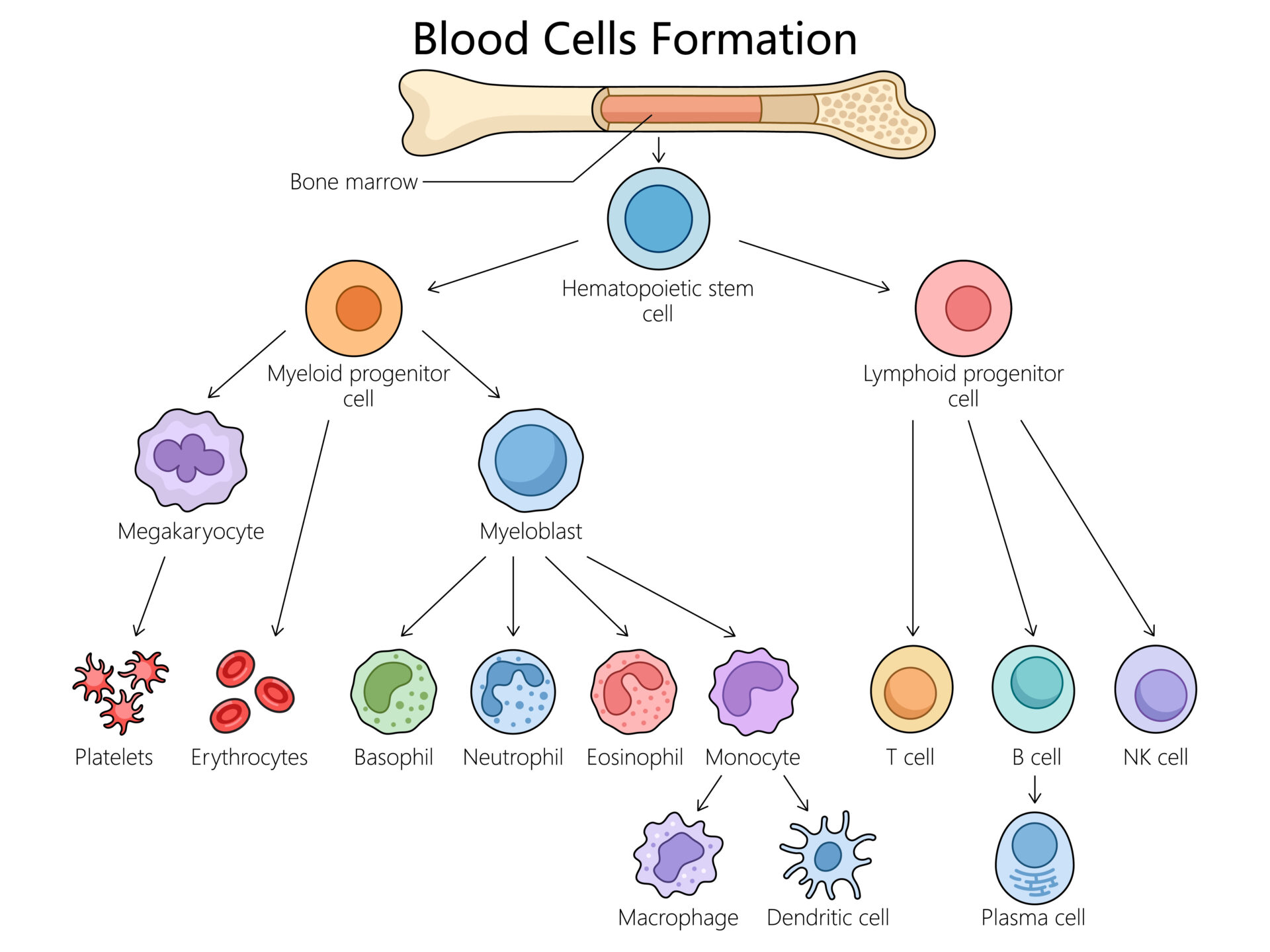

Primary neutropenias, also known as congenital neutropenias arise from mutations in a heterogeneous set of genes, both directly and indirectly, required for normal myelopoiesis. Depending on the culprit gene, there may be pathological changes reflected in the degree of susceptibility to infection, timing of susceptibility to infection, the patient’s physical exam, laboratory values indicating non-hematological organ dysfunction, peripheral blood and bone marrow morphology and immunophenotypes. The specific syndrome is important to identify as these entities are heterogeneous and carry different consequences for patients. Notably, there are certain groups of people (individuals of African, Jewish, Mediterranean, or Middle Eastern descent), who can have what’s known as constitutional or benign ethnic neutropenia. This is important to be aware of, as it does not increase the risk of severe infection or myeloid malignancies as to those due to pathogenic defects in genes essential to normal cell function.

What are congenital neutropenia syndromes?

As mentioned above, these are caused by a heterogeneous set of genetic defects. Congenital neutropenia is an overarching term that groups these conditions together based on what we see clinically:

a patient with a genetic cause driving the failure of their neutrophil responses resulting in predisposed to infection. We detail the genes responsible for the different congenital neutropenic syndromes

in our paper by the stage of myelopoietic maturation they affect and subcellular localization of the defect gen [See Figure 1 (https://jcp.bmj.com/content/jclinpath/77/9/586/F1.large.jpg) and Figure 2 (https://jcp.bmj.com/content/jclinpath/77/9/586/F2.large.jpg)] We provided references to the OMIM database (https://www.omim.org/), which also provides a catalogue of the named conditions. For example, some of the conditions that have been described include cyclic neutropenia, severe congenital neutropenia

(a number of types, including Kostmann disease), GATA2 deficiency, WHIM syndrome, Shwachman–Diamond syndrome, Hermansky–Pudlak syndrome, Cohen syndrome and Barth syndrome.

Molecular studies are critical to the diagnosis of these entities, many of which overlap in their clinical presentation, but general bone marrow studies can hint to specific conditions. In our paper we provide a review of the conditions described to date with a focus on their morphologic presentation in the peripheral blood and bone marrow, as well as cytogenetic and molecular characteristics.

It is important to identify the genetic cause of the neutropenia as the management and risks associated with them vary. For example, some can be treated with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, whereas others do not respond. Others are associated with a predisposition to developing myelodysplastic syndrome or acute leukemia. Some are syndromic and their diagnosis can precede the dysfunction of other body systems. Each neutropenia has its own natural history and, so the patients need individually tailored management.

How are they normally diagnosed?

Clinical presentation varies with the severity of the underlying defect. Some patients present in the first days, weeks, or months of life with recurring infections, even severe ones, like meningitis. A lot of them can be at those sites that are very immediately susceptible, for example, the oral mucosa and gums, tonsils, pharynx. Pulmonary/respiratory infections are common. When a patient with no apparent reason to be immunocompromised is seen clinically, that might start to trigger the question of: What types of infections has the patient had (e.g. respiratory, skin or gastrointestinal), and how frequently do they occur? Is there any family history of similar immune issues? Overall, it requires a focused clinical team to concurrently diagnose a patient’s infection and underlying susceptibility of the patient to that infection.

Hematopoiesis (Adobe Stock.com)

What happens with these rare diseases is that patients bounce around between hospitals who treat the infection. For example, they’ll get admitted for infection at one hospital, be treated and sent home, then they’ll go somewhere else they’ll have these multiple bouts and then hopefully they end up at a hematology, infectious disease, or genetics clinic, who will work up their underlying immunodeficiency.

Combining the clinical, laboratory, and histopathology findings of the bone marrow can indicate a congenital neutropenia, even a differential diagnosis in syndromic cases, but ultimately next generation sequencing panels are required.

What are the challenges of diagnosis?

A large part of the challenge of diagnosing these conditions is that these things are very rare, so it’s not where your mind goes first as a clinician and especially in the non-pediatric world – almost every other secondary cause of neutropenia is going to be the answer before congenital neutropenia. They are also very diverse, they don’t have a common cluster of symptoms beyond susceptibility for infection, and many are not well characterized.

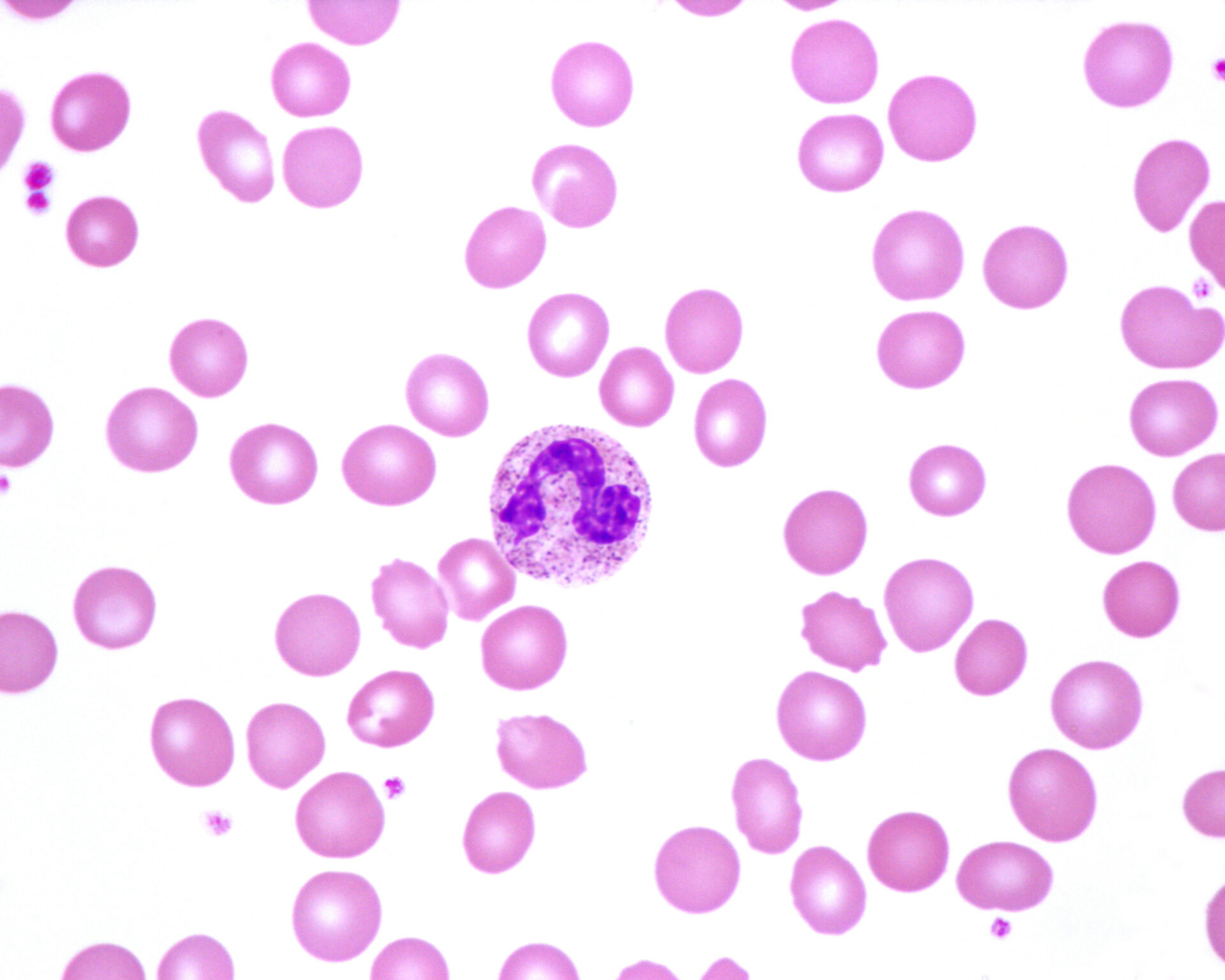

Standard laboratory testing can help identify trends in cycling neutropenia or bone marrow and peripheral blood morphology can be a clue but it’s still pretty non-specific. For example, more than ten different genetic etiologies may underlie myelopoietic arrest at the promyelocyte stage. Other bone marrow findings, for example, myofibrosis or dyspoietic megakaryocytes cytoplasmic vacuolization in bone marrow cells can be seen in any bone marrow specimen from a hundred reactive conditions. Identifying these diagnoses really demands clinical suspicion on top of a good patient history.

Can you envisage anything on the horizon that might improve diagnosis or make diagnosis easier?

In an increasingly digital world, communication between hospitals is getting easier. The availability of regional medical records has become integrated into some medical records systems. A physician’s concern for a congenital neutropenic syndrome may more quickly form on review of the patient’s history. The advances being made in molecular pathology are also making testing more accessible. With time, the costs of testing will fall. As researchers investigate variants of unknown significance arising in patient molecular reports, a better understanding of pathogenesis and hopefully treatment will evolve.

If you had to pass on one take-home message from your knowledge of diagnosing congenital neutropenia syndromes, what would it be?

Patient history is king. If the clinician does not take a full, proper patient history or the pathologist does not carefully review the patient’s medical record, they may never consider that this patient was seen at three other hospitals in last year for infections, or their whole family seems to have issues with like non-healing ulcers. It’s challenging in the context of an increasingly fast-paced clinic and specimen turnover time.

If you do not consider the congenital neutropenia syndromes in your differential, you cannot give their diagnosis. Basic approaches like reviewing the patients complete blood counts over time may show fluctuating counts in a a predictable pattern, for patients with the cyclic neutropenia. In the context of non-hematopoietic organ dysfunction, consideration of syndromic etiologies is important. Concurrent failure to thrive, facial, neurological, osseous, pulmonary, cardiac, gastrointestinal, and genitourinary system abnormalities should prompt a consult with medical genetics. The dyspoietic and dysplastic bone marrow morphology should be considered. While many conditions demonstrate normal findings, many have recurrent findings. These are summarized in the supplementary table of our recent paper (https://shorturl.at/W9Okg).

Normal neutrophil in human blood smear (Adobe Stock.com)

The interviewee

Dr Xenia Parisi MD,

Hematopathology Fellow

Department of Hematopathology,

University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, Texas, USA

Email: xparisi@mdanderson.org

Parisi X, Bledsoe JR. Discerning clinicopathological features of congenital neutropenia syndromes: an approach to diagnostically challenging differential diagnoses. J Clin Pathol 2024;77(9):586–604 (https://shorturl.at/4vTWE).