Diagnosis of acute periprosthetic joint infections in reduced incubation time

With an increasingly elderly population, joint replacement surgery is being performed more and more often. Infection around the prosthesis is becoming a more common reason for revision surgery and appropriate antibiotic treatment benefits from accurate diagnosis of the pathogen(s) involved. Current protocols use a standard 10- to 14-day incubation period but a recent publication has shown that the diagnosis of acute periprosthetic joint infections can be done in a shorter time scale. CLI chatted to Dr van Loo and Dr Morreel (Maastricht University Medical Centre, Maastricht, the Netherlands) to discover more about their findings.

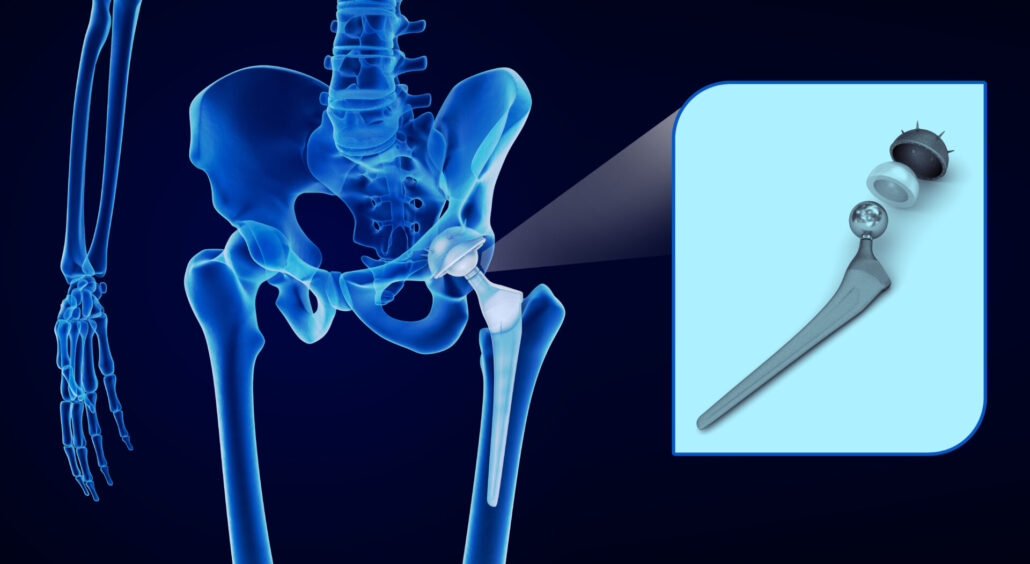

With an increasingly elderly population, joint replacement surgery is becoming more common. When these surgeries go well the patient’s life can be trans-formed. However, what are some of the typical complications that can arise? First of all you can have mechanical problems, for example when the prosthesis isn’t well aligned, but what we see as a trend in the past few years is that infection is becoming the predominant complication and the predominant reason for revision surgery. Revision surgery can involve debriding the implant (removal of dead or infected tissue) or removing it altogether to replace it.

One of the major risks for joint replacement revision surgery is infection

(AdobeStock)

As clinical microbiologists we are only involved when there is infection or suspicion of infection – we don’t see all the other complications that can occur. However, there is a Dutch register of all the implants and reports are provided each year on how many implants were placed, how many revision surgeries were needed and what the reason for revision was. This register shows a trend that infection is increasingly common as the main reason for revision surgery.

As mentioned, when there is infection around the prosthesis, further invasive surgery is required to try to control the infection, either to debride the area or to replace the implant; however, in all cases at least 3 months of antibiotic treatment is required. First, we start off with intravenous (IV) antibiotics. In many cases patients are still in hospital to receive those IV antibiotics or when they go home they have to get a central line so that in itself also has risks. After that, we then switch to oral antibiotics and there are many side effects from the antibiotics so it’s not always easy for the patients, particularly if they’re trying to start their rehabilitation.

If a periprosthetic joint infection is suspected, how is diagnosis usually done?

Multiple samples are always taken during the surgery (i.e. multiple intraoperative samples) that we culture, as culture is still the gold standard method for identification of the pathogen. Along with multiple samples, we use multiple types of culture media such as solid agar plates as well as enriched liquid media such as blood culture bottles and broths which are added to increase sensitivity so that you can also detect pathogens that are slow growing microorganisms, or microbes that just need more nutritious conditions, or for the detection of low-load pathogens. We incubate all cultures for 2 weeks, which also helps us to identify any slow growing microorganisms.

Additionally, in some patients attempts are made to try to diagnose potential infection before the surgery. Here, a sample of synovial joint fluid is taken and sent to the laboratory for culture to try to diagnose before the surgery which pathogen is present so that treatment can begin immediately for that pathogen. Otherwise we have to wait to see what the result of the cultures is. Pre-surgical testing is not always possible to do, though, as there is also the risk of inserting another pathogen.

When the bacterial colonies start to grow and we identify the species, we also perform antimicrobial susceptibility testing at the same time. Depending on how fast the pathogen grows, we can then advise a change from the empiric antibiotic treatment that may have already been initiated to a specific therapy that should be more effective.

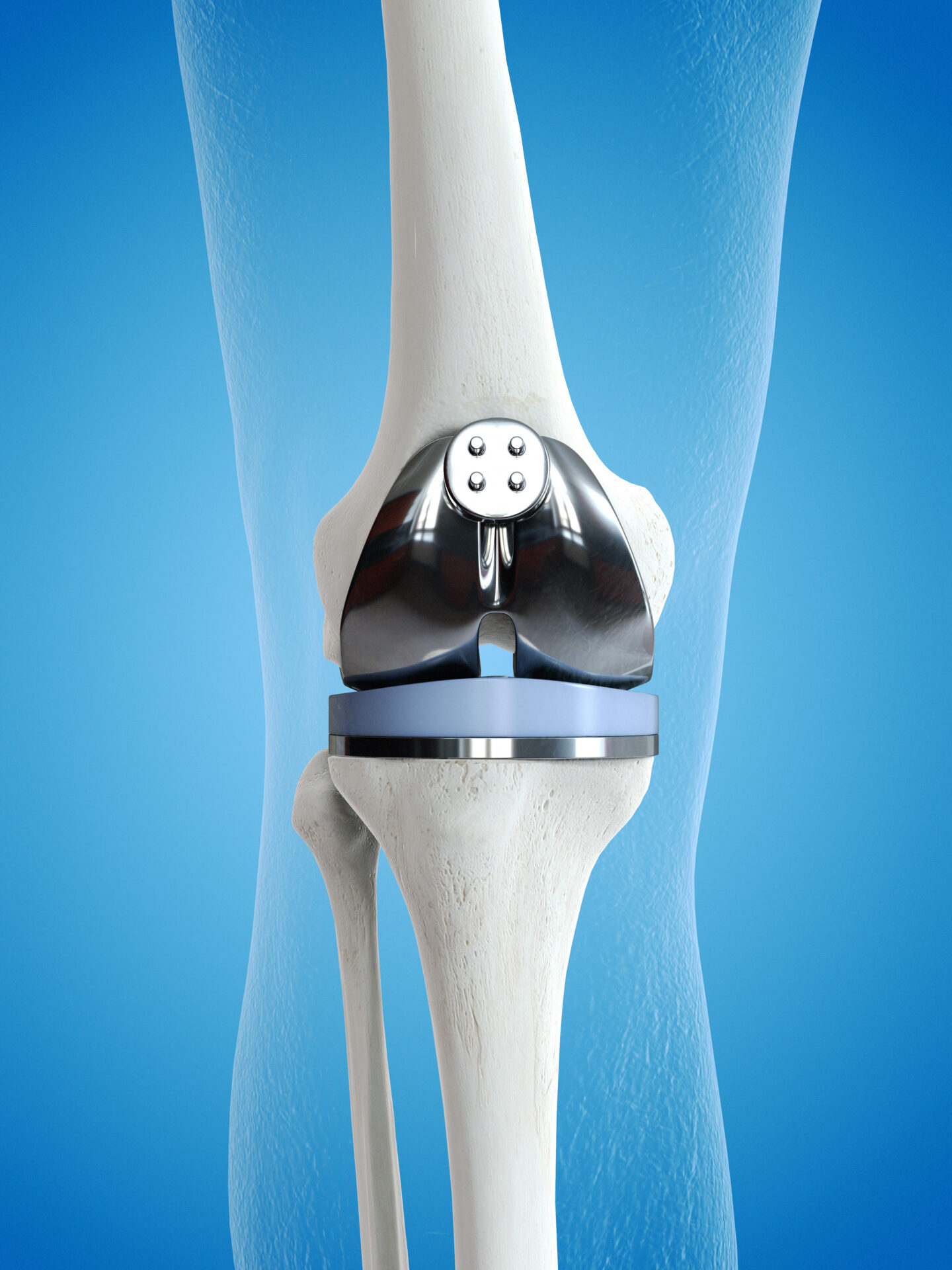

(AdobeStock)

What are the challenges/limitations of these methods?

As you can imagine it’s a lot of work, it’s very laborious for the laboratory personnel because there are multiple samples per patient each grown with multiple media types. Also I would say the most important limitation is that the culture time can be prolonged. Most pathogens can be cultured within a few days but if there is a strong suspicion of an infection the culture time has to be extended to up to 2 weeks to be able to rule it out. For the most part, the sensitivity of the culture methods is already at its maximum, so that is not something that can really be improved. However, culture methods are less sensitive for fastidious organisms, such as anaerobic bacteria. Also, of course, culture is influenced by antibiotic use, for example if the patient has already received antibiotics it can influence the culture process and that also makes the results difficult to interpret.

Another challenge that we struggle with daily is that of course a lot of pathogens for prosthetic joint infections are skin commensal bacteria so it’s always difficult to differentiate between commensal bacteria and true pathogens. This is the reason why we try to quantify the presence of the bacteria but this is not always that easy when you have one sample with a possible pathogen. Our findings are always followed by a discussion in our multi-disciplinary team meeting with the surgeon and our results are always placed into context with patient’s presentation and how high the clinical suspicion of infection is.

One of the drawbacks of the 2-week incubation time is that patients are treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics during that period and if eventually the culture is negative then there has been 2 weeks of unnecessary antibiotic use – one might even say misuse – which is important to bear in mind and to minimize when there is the very real problem of emerging antibiotic resistance.

What tips, techniques and advice do you have for overcoming these limitations?

Duration of culture

We first of all looked at the different categories of prosthetic joint infections, as these can be classified as early acute, late acute and late chronic infections, and we saw that in the event of acute infections – both early and late – those were really the fast growing microorganisms and almost all of these periprosthetic joint infections can be identified within 1 week. This is helpful for the clinician, as if the patient has an acute presentation and a microorganism hasn’t grown or been identified after a week we can safely say that another one won’t grow in the second week so the antibiotics can be stopped. In most cases, of course, the pathogen will have already been identified in the first week and then there are no concerns that further pathogens will appear. For the more chronic infection mentioned above, these are caused by fastidious, slow-growing microorganisms, in which case the prolonged incubation time is necessary.

Media

Regarding the media, we employ blood culture bottles and broths, but actually we found that the broths did not add that much value to the cultures; hence, we would advise the use of blood culture bottles.

Sample

Additionally, when bacteria attach to the surface of the prosthesis they form a biofilm which is actually an extracellular matrix in which the bacteria are encapsulated. This makes it difficult for antibiotics to reach them and also makes it very hard to remove them from the implant, which is one of the most common reasons for removal and replacement of the implant. For culturing the bacteria, we therefore use sonication to release the bacteria from the biofilm on the surface of the removed prosthesis into the sterile fluid which greatly improves the recovery of bacteria. We have found that sonication to generate a sonication fluid sample in combination with anaerobic blood culture bottle really increased our culture sensitivity.

Are there any future/further developments on the horizon that will improve diagnosis of periprosthetic joint infections?

We think there’s a place for molecular diagnostics in the field of bone and joint infection diagnosis and in recent years there have been some developments. However, this is not employed regularly as the first step. Culture will still be relevant, especially for susceptibility testing, but in terms of speed for ruling out infection molecular diagnostics will have a more prominent role. We are looking at different techniques to determine which will be most appropriate. Of course, the method needs to be sensitive and specific, but it also needs to be practical for the lab, such as how we actually use these techniques, and in what situation they are most cost-effective. We are retrospectively testing sonication fluid samples and comparing two different molecular diagnostics techniques to the usual culture method to see if we can expedite turnaround times. I think it will be particularly useful for patients where there is a suspicion of an infection but it’s not really that clear, perhaps there is a slow growing microorganism and we can rule out infection more quickly, stop antibiotic treatment and discharge the patients from hospital. When we finish that we are going to perform this in a prospective study as well and then we can really see what the benefit is of this kind of molecular screening.

There are a number of questions to investigate around molecular screening. For example, it’s still more expensive than traditional culture methods and we so need to ascertain how best to use it – do we need one sample or do you still need to have multiple samples? Also, because some methods are very sensitive, it can still be difficult to differentiate contaminating skin commensal bacteria present in low concentrations from pathogens, so there’s a lot of discussion about which thresholds for distinguishing infection from contamination.

The authors

Inge H.M. van Loo MD, PhD

Consultant Microbiologist

Department of Medical Microbiology, Infectious Diseases and Infection Prevention, Maastricht University Medical Centre, Maastricht, the Netherlands

Care and Public Health Research Institute (CAPHRI), Maastricht University, Maastricht, the Netherlands

Email address: ihm.van.loo@mumc.nl

Elizabeth Morreel MD

Consultant Microbiologist

Department of Medical Microbiology, Infectious Diseases and Infection Prevention, Maastricht University Medical Centre, Maastricht, the Netherlands

Care and Public Health Research Institute (CAPHRI), Maastricht University, Maastricht, the Netherlands

Email address: elizabeth.morreel@mumc.nl

For further information see:

Morreel ERL, van Dessel HA, Geurts J, Savelkoul PHM, van Loo IHM. Prolonged incubation time unwarranted for acute periprosthetic joint infections. J Clin Microbiol 2025;63(2):e0114324

(https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.01143-24).