Digital pathology – late starter, becoming indispensable

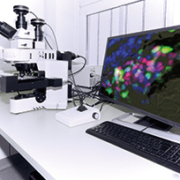

Digital pathology is a computer-based imaging environment which enables the analysis and storage/retrieval of information from a digital slide. It is considered to be one of the most promising recent developments in diagnostic medicine, with the potential to provide better, quicker and more cost-effective diagnosis and prognosis, especially for managing diseases like cancers.

Digital pathology is closely associated with the term ‘virtual’ microscopy, since images are viewed remotely, without a microscope or slides, after being transferred over a hospital network or the Internet.

Whole slide imaging

A key technology driver of digital pathology is whole slide imaging (WSI), sometimes also described as whole slide digital imaging. WSI scans and converts specimen glass slides into digital images, which are made accessible by software for display on a computer monitor. Digitized slides allow analysis via computer algorithms, which automate the counting of structures and quantitatively classify tissue condition. This task is otherwise performed, painstakingly, by pathologists using a microscope to view, analyse and stain tissue slides.

The pace of development in virtual microscopy has accelerated. Recent advances in scanning technology allow for achieving over 100,000 dpi resolutions, in other words approaching the level of optical microscopes.

Cancer staging versus grading: the role of pathology

Digital pathology offers particular promise in the grading of tumours. Tumour ‘grade’ is different from the ‘stage’ of a cancer.

Cancer stage refers to the size of a tumour and whether or not cancer cells have spread in the body.

Pathologists play a role in providing staging information, alongside physical examination, imaging and lab tests. Physicians select different combinations of each of these modalities for staging.

By contrast, grading is principally a pathologist’s area of expertise.

Grading scales

The grade describes a tumour and the likelihood of its growth and spread, based on the abnormality of tumour cells as seen under a microscope.

Tumours are typically graded on a 1-4 scale. A lower grade indicates better prognosis, while higher grades tend to grow and spread more quickly, thus requiring more aggressive treatment. Grade 1 tumours are usually described as “well-differentiated” with tumour cells and tissue appearing close to normal. Grade 3 and 4 tumours look least like normal cells and tissue. They are often described as “poorly differentiated” or “undifferentiated,” and tend to grow and spread faster than tumours with a lower grade.

The pathologist and visual perspectives

One of the strongest arguments in favour of digital pathology is that microscopes require pathologists to always possess keen eyesight to determine the ‘differentiation’ required for assigning a grade to a tumour. Like many other healthcare professionals, pathologists are also burdened by heavy workloads. This, in turn, can impact on visual acuity and interpretation.

Digitized images, in contrast, can quantify the differentiation (and grading) process via algorithms, reduce the risk of human error and improve accuracy.

Glass slides and inconsistent interpretation

The challenge of consistency in pathology has been a vexing issue for some time. In March 2015, the ‘Journal of the American Medical Association’ (JAMA) published the results of a study to “quantify the magnitude of diagnostic disagreement among pathologists.” The study focused on pathologists interpreting breast biopsies from glass slides in eight US states and noted that although a breast pathology diagnosis provided “the basis for clinical treatment and management decisions,” its accuracy was “inadequately understood.” Among its findings – one in four cases did not show consonance of individual pathologists’ interpretations with expert consensus.

Disagreement with the reference diagnosis was statistically significant among pathologists who interpreted lower weekly case volumes or worked in smaller practices – confirming the observation about the inverse correlation between workload on the one side, and quality of eyesight on the other.

Digital pathology and second opinions

To address such variations in diagnoses, second opinions have become commonplace. However, for glass slides, a second opinion entails long lead times and complexities in a pathologist’s workflow (from glass packaging and transport, and at the other end, unpacking materials, verifying sample/reference case, registering the case in a laboratory information system etc.). Many pathologists are forced to cope quietly with a difficult decision – weighing up the value of a second opinion against the extra waiting time for a patient.

Digital pathology streamlines access to second opinions, enabling quicker and more accurate delivery of diagnoses. Both these correlate strongly to successful treatment outcomes. Telemedicine has taken explicit note about this potential. In 2014, the American Telemedicine Association published draft guidelines on the use of digital pathology in telemedicine.

Radiology and pathology: collaborative cousins

Pathology is involved in almost all cancer diagnoses.

Digital pathology is being seen as both a catalyst and enabler for more collaboration across specialties, beginning with radiology – one of the first fields to be digitized.

A September 2012 ‘BMC Medicine’ article titled ‘Integrating Pathology and Radiology Disciplines: An Emerging Opportunity?’ argues for an end to traditional pathology-radiology workflows where the two specialties “form the core of cancer diagnosis” but remain “ad hoc and occur in separate ‘silos’, even though “the opportunity for pathology-radiology integration to improve patient care is great, and more importantly, the tools to achieve this exist.”

DICOM and HIPAA

Until recently, digital pathology was hampered by a lack of standards for storing and transferring images, among other things, to be more in line with modern PACS systems storing radiology images. However, this was successfully addressed by DICOM (Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine) supplement for digital pathology (No. 145), which was released in July 2010.

According to a May 2011 report in the ‘Journal of Pathology Informatics’, the DICOM supplement standard was hailed by “everyone involved in the field of digital pathology” since it made it easier for hospitals “to integrate digital pathology into their already established systems without adding too much overhead costs.”

Besides, it was seen to enable different vendors developing scanners “to upgrade their products to storage systems that are common across all systems.”

There is already sufficient integration between digital pathology systems (DPS) and anatomic pathology laboratory information systems (APLIS) to provide pathologists with access to images and image analysis data from either, and input it to a Patient Report. On the regulatory front, DPS vendors are also well placed to support HIPAA compliance by encrypting protected health information (PHI) metadata such as slide labels, hospital, patient and specimen information, etc.

A March 2007 issue of ‘Neuroimage’ points to another major attribute of digital pathology, namely the capacity for data mining.”

Digital pathology in medical education

So far, the key application of digital pathology has been in teaching. As the University of Minnesota observes, “virtual microscopes can transform traditional teaching methods by removing the reliance on physical space, equipment, and specimens to a model that is solely dependent upon computer-internet access. This rich database is enhanced with patient clinical presentations, laboratory data, comprehensive slide interpretations, and diagnoses.”

Also in the US, a partnership between Oklahoma University Medical Center (OUMC), the Children’s Hospital, and the University of Oklahoma College of Medicine, observes that digital pathology promotes efficiency and cost-effectiveness as a teaching tool as well as in using digital slides for consultation with patients referred to OUMC from other hospitals.

Barriers to digital pathology

Barriers to the more widespread implementation of digital pathology have also been recently assessed. These concern economics (mainly return on investment) and consistency and methodological robustness in WSI.

ROI

Unlike digital radiology which has a longer legacy and a stronger case for ROI (return on investment) – principally in terms of replacing film, the arguments for digital pathology are less obvious.

A study by a Swedish hospital found the following justifications for digital pathology: savings of time in administrative tasks (13%), slide review (6%) and supervision (3.1%), alongside an increase in efficiency of administrative tasks (100%), supervision (33%) and slide review (16%).

In terms of productivity per pathologist, the gain attained by digital pathology was 10%, while overall time savings were 24%.

Consistency in digital pathology interpretations

The second challenge facing digital pathology has been to determine the difference of interpretation of whole-slide images from glass-slide interpretation in difficult surgical cases, and the impact of such differences. This issue has been the subject of a study, with an article on the findings published in the December 2009 issue of the ‘Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine’.

Overall concordance between digital whole-slide and standard glass-slide interpretations was 91%, with agreement among digital, glass, and reference diagnoses in 85% of cases. 9% of digital cases were discordant with both reference and glass diagnoses. This was due to incorrect digital whole-slide interpretation, mainly because of issues such as fine resolution and navigating ability at high magnification.

FDA approval

One of the biggest obstructions to the growth of digital pathology has been the absence of approval by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for primary diagnosis. Several EU countries allow pathologists to use WSI for primary diagnosis, with some flexibility. For instance, in Sweden, slides are digitally scanned but also physically delivered to a consulting pathologist who has the choice to review the slides on screen, in the microscope, or both.

However, much of the technology development in digital pathology – as well as vendor interest – has originated in the US, and it is evident that freeing up digital pathology for primary diagnosis in that country would galvanize use worldwide.

US manufacturers have so far been able to market digital pathology technology for Research Use Only (RUO). Several vendors have also received one or more FDA 510 (k) clearances, with a key justification being manual and/or quantitative analysis of immunohistochemistry and/or in situ hybridization.

More developments are in the pipeline.

In February 2015, the FDA issued draft guidance for the technical performance assessment of digital pathology WSI devices. This followed an FDA Hematology and Pathology Devices Panel meeting six years previously to obtain industry feedback on replacing glass slides and conventional microscopy with whole slide images (WSI) for the purpose of rendering surgical pathology diagnosis.

On its part, the Digital Pathology Association (DPA) expects the draft guidance to lead to follow-on guidance and clarify the FDA’s expectations for WSI regulatory submissions, enabling increased access and adoption of digital pathology for clinical use.