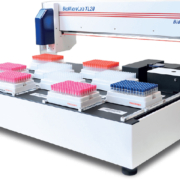

Beckman Coulter assists expansion of national network of HIV testing in Uganda

Despite significant progress in its prevention and treatment, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) remains a serious public health threat across the globe. The United Nations programme UNAIDS has led the global effort to address the HIV/ AIDS crisis and has set out its 90-90-90 target: 90 percent of all people living with HIV (PLHIV) will know […]