Infectious diseases, in particular lower respiratory infections and diarrhoea are among the top ten causes of death worldwide [1]. Many infectious diseases can be considered ‘syndromes’, i.e. a collection of symptoms that do not point to a specific causative agent. A ‘syndromic approach’ in diagnostics means to achieve, by a single test, a diagnosis without taking into account the symptoms themselves. In molecular diagnostics (MDx) of infectious diseases, this means the use of multiplex PCR panel assays to simultaneously detect genetic material from pathogens of different species and even different taxonomic levels, such as bacteria, viruses, parasites and fungi.

by Dr. Antoinette A. T. P. Brink and Dr. Guus F. M. Simons

Clinical syndromes and their causal pathogens

Respiratory infections

Respiratory infections are highly prevalent and the possible causative agents include several typical and atypical bacteria, as well as many viruses. Among the latter, the influenza virus particularly is associated with morbidity and mortality. As influenza A viruses can infect multiple hosts, including not only humans but also birds and swine, these viruses can undergo antigenic shifts that may result in pandemics such as the 2009 ‘Mexican flu’. Nowadays, many molecular diagnostics (MDx) tests are able to distinguish influenza A virus subtypes associated with non-human hosts, such as H5N7 avian flu. The presence of such a subtype in a patient with respiratory illness may be indicative for zoonosis, which increases the risk of a new pandemic. Besides influenza A virus, syndromic MDx panels generally detect influenza B virus, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) A and B, adenovirus (AdV), human metapneumovirus (hMPV), parainfluenza virus (PIV) types 1–4 and human coronavirus (hCoV) types 229E, OC43, NL63 and HKU1, rhinovirus (RV) and enterovirus (EV). Bocavirus is not always included, although it is considered an important pathogen especially in children [2].

The merit of testing a broad respiratory panel is illustrated by a study conducted by the Dutch National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM) among community-dwelling elderly receiving annual influenza vaccination. Vaccine effectiveness was studied by determining the relative contribution of influenza and other respiratory pathogens to influenza-like illness (ILI), using an assay that detects 22 respiratory pathogens simultaneously (RespiFinder®) As expected, vaccination reduced the incidence of influenza, but the number of ILI episodes was similar between vaccinated and non-vaccinated individuals; non-Influenza viruses replaced influenza as a cause of ILI in vaccinated individuals [3].

This finding is in line with the recommendation of the American Society for Microbiology working group for respiratory virus testing not to restrict testing for specific respiratory viruses during certain seasons because with global travel, many ‘seasonal’ viruses can cause disease throughout the year [4]. Moreover, testing should not be restricted to certain patient populations, e.g. testing for RSV/hMPV only in children, because these viruses may cause severe disease in adults as well.

For fastidious bacteria causing atypical pneumonia, such as Legionella pneumophila, Chlamydophila pneumoniae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Bordetella pertussis and B. parapertussis, MDx has largely replaced conventional culture.

For Streptococcus pneumoniae and other bacteria associated with typical pneumonia, PCR is not ready to replace conventional culture because these bacteria belong to the normal oral flora. Quantitative detection is necessary to distinguish colonization from infection, but sample quality criteria for this are lacking. Moreover, conventional culture remains necessary for antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

Gastroenteritis

Most gastroenteritis (GE) panels detect an extensive list of viruses, bacteria and parasites. It is self-evident that GE viruses such as norovirus, adenovirus types 40 and 41, and rotavirus are included. Although the clinical course of sapovirus and human astrovirus (HAstV) infections is generally milder than that of, for example, norovirus, they should be included in routine testing to identify outbreaks and to ensure proper care of patients at risk for severe complications, such as infants, elderly and immuno-compromised patients.

The parasites Cryptosporidium spp., Entamoeba histolytica and Giardia lamblia are included in all GE panels because their pathogenicity is well established. For Dientamoeba fragilis this is still a matter of debate, but it should be considered the causal factor of GE symptoms – and treated appropriately – after other causes have been excluded [5].

Regarding GE-causing bacteria, most commercially available tests detect the most common pathogenic Escherichia coli types (EHEC, ETEC, STEC, EPEC, and IEIC), Salmonella spp. and Yersinia enterocolitica. For Campylobacter it is important to detect all pathogenic species, i.e. C. jejuni, C. coli, C. upsaliensis and C. lari [6], the latter two of which are not included in some commercially available assays.

In contrast, for Vibrio cholerae it is important to distinguish the only two serotypes that can cause outbreaks and infections should be treated actively, to avoid overtreatment.

Additional pathogens may be included, but test results may be difficult to interpret owing to (i) frequent contamination from the environment or reagents (e.g. Aeromonas spp.) or (ii) conflicting data regarding pathogenicity (e.g. Plesiomonas shigelloides).

Infections of the central nervous system

The differential diagnosis for patients with suspected meningitis/encephalitis (ME) includes infectious as well as non-infectious causes that cannot be distinguished on the basis of symptoms. A recent study showed that in the majority of patients suspected of a central nervous system (CNS) infection, the etiology could not be found even with the most comprehensive commercially available MDx tests [7]. In line with this, the use of a diagnostic stewardship approach is advocated, including cerebrospinal fluid white blood cell count to prevent unnecessary use of expensive tests [8]. Having said that, true CNS infections are medical emergencies that require rapid pathogen identification to allow timely and appropriate clinical intervention.

Causative agents of CNS infections include enteroviruses, parechoviruses and all eight members of the human herpes virus family, the most prevalent of which are herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2. The other herpes viruses, such as cytomegalovirus, varicella-zoster virus, human herpes virus 6, and Epstein-Barr virus, are mostly seen in immunocompromised patients such as transplant recipients [9].

Measles and mumps viruses may also cause CNS infections, especially in regions where vaccine coverage is sub-optimal due to, for example, a weak healthcare system or vaccine refusal. Of note, when this paper was drafted, four countries in the European Union (Albania, Czechia, Greece and the United Kingdom) had recently lost their measles elimination status previously assigned by the World Health Organization.

Meningitis-causing bacteria usually belong to the normal oropharyngeal flora, and may enter the CNS by anatomic defects in the natural barriers, or defects in the immune system. Streptococcus pneumoniae is the most common cause of community-acquired meningitis in non-neonates worldwide, followed by Neisseria meningitidis. Other bacterial pathogens in meningitis are Listeria monocytogenes, Haemophilus influenzae, Staphylococcus aureus and Borrelia burgdorferi.

Vaccination campaigns against various serogroups of these bacteria are ongoing. As serogroup replacement occurs as a consequence of vaccination, it is important that in vitro diagnostic kits detect all serogroups, and that assay designs are checked periodically for this.

Sexually transmitted infections

Various bacteria, parasites and viruses can cause sexually transmitted infections (STI).

STIs can be non-symptomatic, but if left untreated they can have severe sequelae including permanent infertility or ectopic pregnancy.

STI test panels should at least include Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Mycoplasma genitalium and Trichomonas vaginalis. For a syndromic approach, herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 and Treponema pallidum should be included.

The editorial board of the European STI Guidelines recommends not to test routinely for Mycoplasma hominis and Ureaplasma parvum. In addition, in men with symptomatic urethritis, Ureaplasma urealyticum should only be treated after C. trachomatis, N. gonorrhoeae and M. genitalium have been excluded [10].

Several subtypes of STI require non-standard therapy. For example, the ‘L’ serovars of C. trachomatis can cause lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV) and proctitis, which should be treated differently from other C. trachomatis infections [11].

Furthermore, N. gonorrhoeae strains have emerged that are resistant to all antimicrobials used for treatment, owing to point mutations and/or genetic recombination with commensal Neisseria species [12]. In addition, the change from doxycycline to azithromycin as the first-line treatment for C. trachomatis and non-gonococcal urethritis has resulted in selection of macrolide-resistant M. genitalium strains [13]. Fortunately, such pathogen properties can be distinguished by molecular methods and, in fact, several commercially available multiplex MDx assays can do this already.

MDx methods for syndromic approach

Laboratory-developed tests

Laboratory-developed PCR assays for infectious diseases have been in use since the early 1990s [14].

Generally, laboratory-developed tests (LDTs) run on conventional 96-well realtime PCR systems, allowing the testing of large batches of samples. Most LDTs are TaqMan-based, generally limiting multiplexing to four targets per reaction. A syndromic approach is, therefore, only possible by running several reactions (up to eight to cover a full respiratory panel) per sample, which limits throughput.

Although the cost-of-goods for LDTs is low, testing can be laborious and time-consuming and requires highly skilled laboratory personnel.

Commercial: medium to high throughput

Clinical laboratories needing a syndromic approach and medium to high throughput may use commercial assays instead of LDT. To exceed the multiplexing capacity of LDTs, manufacturers have developed proprietary methods. For example, Luminex’s platform uses fluorescently labelled bead array technology with dedicated instruments. Korean Seegene’s assays include melting curve analysis or differential detection temperatures to allow distinction of multiple targets per fluorescent channel.

Commercial: random access/low throughput

Examples of commercial random access systems are the FilmArray by bioMérieux, the QIAstat-Dx by QIAGEN and the ePlex by GenMark. The high price for the dedicated instruments and high price-per-test can be an argument against implementation in routine use if large amounts of samples are processed. Hence, these systems are particularly suitable for point-of-care purposes or when laboratory skills of personnel are limited. However, the ease-of-use may conceal to inexperienced users that these tests are actually very sensitive, and careful reaction set-up and cleanliness of the environment are needed to avoid false positives. It is self-evident that (unexpected) positive results should be interpreted in the context of clinical symptoms. Moreover, the ISO 15189 standard for medical laboratories recommends users to run additional control materials from independent third parties.

Summary

A syndrome-based approach using broad panel MDx assays may assist in timely diagnosis of respiratory infections, GE, CNS infections and STI.

Syndrome-based MDx results in a decrease in the number of chest radiographs, reduced admission rates, fewer barrier nursing days [15], shorter duration of hospitalization, more appropriate prescription of antivirals, better antibiotic stewardship and decreased duration of antimicrobial use [16–18], which is likely to result in less antibiotic resistance in the long term.

In addition, broad panel tests provide useful information about epidemiology, seasonality and possibly clinically relevant co-infections

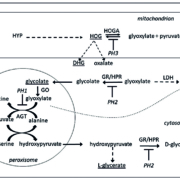

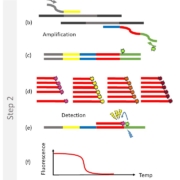

Figure 1: Example of high multiplexing (the 2SMARTFinder® principle of Dutch firm PathoFinder)

Schematic representation of the PathoFinder 2SMARTFinder® test principle: (a) Step 1 (pre-amplification): specific multiplex target enrichment. (b) Step 2 (2SMART reaction): signal amplification by means of 2SMART primers each consisting of a targetspecific sequence (yellow/blue) and a universal sequence (grey/green). Each reverse 2SMART primer contains a stuffer/barcode sequence (red) for detection. The combined action of the 2SMART primers and the universal primers, of which the reverse is labelled with fluorescein amidites (FAM), results in the generation of (c) a FAM-labelled PCR product. (d) The reaction mixture contains labelled SMART probes complementary to each stuffer. (e) When a probe hybridizes to its corresponding stuffer in the reaction product, the FAM label acts as a Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) donor and the label in the SMART probe as an acceptor, resulting in the emission of light that can be measured in real-time. Finally, the temperature is increased, resulting in dissociation of the probe-stuffer hybrid and a sharp decline in fluorescence (f). The negative derivative of this graph shows the actual melting peaks (g). The stuffer/probe sequence determines the position of the melting peak and reveals which pathogen was present in the sample. −Δ(F)/dT, negative derivative of the change in fluorescence (F) as a function of temperature (T).

Figure 2: Typical result read-out on LightCycler 480

Example of the read-out of the RespiFinder® 2SMART assay mix 1 in the carboxyrhodamine (ROX™) channel of a LightCycler 480 II real-time PCR instrument. AdV, adenovirus; hMPV, human metapneumovirus; Inf A, influenza A virus; Inf B, influenza B virus; RSVA, respiratory syncytial virus A; RSVA, respiratory syncytial virus B

References

1. Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V, Abraham J, Adair T, Aggarwal R, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. The Lancet 2012; 380: 2095–2128.

2. Ma X, Conrad T, Alchikh M, Reiche J, Schweiger B, Rath B. Can we distinguish respiratory viral infections based on clinical features? A prospective pediatric cohort compared to systematic literature review. Rev Med Virol 2018; 28: e1997.

3. van Beek J, Veenhoven RH, Bruin JP, van Boxtel RAJ, de Lange MMA, Meijer A, Sanders EAM, Rots NY, Luytjes W. Influenza-like illness incidence is not reduced by influenza vaccination in a cohort of older adults, despite effectively reducing laboratory-confirmed influenza virus infections. J Infect Dis 2017; 216: 415–424.

4. Ginocchio CC, McAdam AJ. Current best practices for respiratory virus testing. J Clin Microbiol 2011; 49: S44–S48.

5. Van Gestel RSFE, Kusters JG, Monkelbaan JF. A clinical guideline on Dientamoeba fragilis infections. Parasitology 2018; 1–9.

6. Klena JD, Parker CT, Knibb K, Ibbitt JC, Devane PML, Horn ST, Miller WG, Konkel ME. Differentiation of Campylobacter coli, Campylobacter jejuni, Campylobacter lari, and Campylobacter upsaliensis by a multiplex PCR developed from the nucleotide sequence of the lipid A gene lpxA. J Clin Microbiol 2004; 42: 5549–5557.

7. Sall O, Thulin Hedberg S, Neander M, Tiwari S, Dornon L, Bom R, Lagerqvist N, Sundqvist M, Molling P. Etiology of central nervous system infections in a rural area of Nepal using molecular approaches. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2019; 101(1): 253–259.

8. Messacar K, Robinson CC, Dominguez SR. Letter to the editor: economic analysis lacks external validity to support universal syndromic testing for suspected meningitis/encephalitis. Future Microbiol 2018; 13: 1553–1554.

9. Chadwick DR. Viral meningitis. Br Med Bull 2005; 75–76: 1–14.

10. Horner P, Donders G, Cusini M, Gomberg M, Jensen JS, Unemo M. Should we be testing for urogenital Mycoplasma hominis, Ureaplasma parvum and Ureaplasma urealyticum in men and women? – a position statement from the European STI Guidelines Editorial Board. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2018; 32: 1845–1851.

11. Ceovic R, Gulin SJ. Lymphogranuloma venereum: diagnostic and treatment challenges. Infect Drug Resist 2015; 8: 39–47.

12. Ameyama S, Onodera S, Takahata M, Minami S, Maki N, Endo K, Goto H, Suzuki H, Oishi Y. Mosaic-like structure of penicillin-binding protein 2 gene (penA) in clinical isolates of Neisseria gonorrhoeae with reduced susceptibility to cefixime. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2002; 46: 3744–3749.

13. Jensen JS. Mycoplasma genitalium: yet another challenging STI. Lancet Infect Dis 2017; 17: 795–796.

14. Claas HC, Wagenvoort JH, Niesters HG, Tio TT, Van Rijsoort-Vos JH, Quint WG. Diagnostic value of the polymerase chain reaction for Chlamydia detection as determined in a follow-up study. J Clin Microbiol 1991; 29: 42–45.

15. Goldenberg SD, Bacelar M, Brazier P, Bisnauthsing K, Edgeworth JD. A cost benefit analysis of the Luminex xTAG Gastrointestinal Pathogen Panel for detection of infectious gastroenteritis in hospitalised patients. J Infect 2015; 70: 504–511.

16. Rappo U, Schuetz AN, Jenkins SG, Calfee DP, Walsh TJ, Wells MT, Hollenberg JP, Glesby MJ. Impact of early detection of respiratory viruses by multiplex PCR assay on clinical outcomes in adult patients. J Clin Microbiol 2016; 54: 2096–2103.

17. Andrews D, Chetty Y, Cooper BS, Virk M, Glass SK, Letters A, Kelly PA, Sudhanva M, Jeyaratnam D. Multiplex PCR point of care testing versus routine, laboratory-based testing in the treatment of adults with respiratory tract infections: a quasi-randomised study assessing impact on length of stay and antimicrobial use. BMC Infect Dis 2017; 17: 671–671.

18. Echavarria M, Marcone DN, Querci M, Seoane A, Ypas M, Videla C, O’Farrell C, Vidaurreta S, Ekstrom J, Carballal G. Clinical impact of rapid molecular detection of respiratory pathogens in patients with acute respiratory infection. J Clin Virol 2018; 108: 90–95.

The authors

Antoinette A.T.P. Brink* PhD, Guus F.M.

Simons PhD PathoFinder B.V., 6229 EG Maastricht,

The Netherlands

*Corresponding author

E-mail: antoinette.brink@pathofinder.com