Novel approach to proficiency testing allows insight into areas for improvement in non-small cell lung cancer biomarker analysis

Although great developments have been made in treating lung cancer, it remains the most common cause of cancer deaths, largely because patients present late with advanced disease. Timely and accurate reporting of biomarker analysis is crucial for directing physicians to the most appropriate therapy for the patient. CLI chatted to Dr Brandon Sheffield (molecular pathologist and Medical Director of the Division of Advanced Diagnostics at the William Osler Health System in Canada) to discover more about their findings from their recent proficiency testing exercise.

Why is biomarker testing important in the diagnosis of non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC)?

So, whether you’re in Canada or the UK, lung cancer is our number one cause of cancer-related death – we have a serious epidemic in in the Western world and globally. It’s the biggest killer of Canadian women; lung cancer takes more lives than breast cancer, colon cancer and pancreas cancer combined.

We’ve made tremendous strides in the treatment of lung cancer, particularly with new therapies that are available, as well as other improvements to surgery and screening. With all of the new treatments, whether they be immunotherapy, targeted therapy or even a new class of drugs – antibody-drug conjugates – every single one of these requires a laboratory-based biomarker test in order to prescribe. Additionally, these are now being used not just for the advanced patients that have metastatic disease, but also in early stage cancer to boost our chances of cure after surgical resection or radiotherapy. So biomarker testing is critical for this disease and the results have to be available to doctors and their patients. They have to be accurate but one thing that our study really focused on is that they have to be timely. The majority of lung cancer patients still present with advanced or metastatic disease – over half of them in both Canada and the UK. Unfortunately, the death rate for those patients is approximately 4% per week, if not more. In Canada, on average, patients might have to wait over a month, sometimes two months, in order to get those results, and so there’s a significant chance of death or deterioration while they’re waiting on those results. Then, because of the delay, there’s also a chance that an oncologist will just go ahead with treatment because either they are frustrated or the patient’s frustrated and don’t want to wait or they can’t wait. We know that if a patient begins treatment without biomarker results, their outcome is going to be much worse than if they had biomarker-informed therapy. So, that in a nutshell is why biomarker testing is important for lung cancer patients. Actually, it’s important for all cancer patients but lung cancer treatment has really led the way in terms of precision medicine, but management of every single tumour type is now moving in this direction where precision treatment is more the norm rather than the exception.

What are the biomarkers that are analysed and how do they impact disease management?

Yeah, that’s a great question. It’s over 20 years ago we first discovered that lung cancer that carries a particular mutation in the EGFR (epidermal growth factor receptor) gene would be amenable to EGFR-inhibitor therapies. So, starting in around the early 2000s, we would test lung cancers for mutations in this particular gene. After that we discovered that there were additional subtypes of lung cancer with ALK (a transmembrane tyrosine kinase receptor) fusions (formed from gene rearrangements) and these were amendable to ALK inhibitors. Over the next two decades we saw numerous changes come with additional EGFR inhibitors, additional ALK inhibitors, but then also a real explosion in the number of different genetic driver alterations that we see within a lung cancer. So now fast-forward to today, we’ll be using a comprehensive genomic profiling not to do single gene testing but to run a panel of usually around 50 genes or more to ask the open-ended question: What is driving this lung cancer? And almost every single tumour will have some identifiable aberration within the DNA. Then we’ll also be checking for protein expression with additional targets such as PD-L1 (programmed death-ligand 1) which is a marker for immunotherapy, looking at protein expression for receptors like the MET receptor tyrosine kinase, as well as KRAS, BRAF, ROS1, NTRK, ERBB2 (HER2), among others. Really, now, for every single patient we will try to identify some underlying genetic aberration and many of those are associated with targeted therapies or targeted approaches. Some of those have well-established treatments, like EGFR inhibition, and some of those have more emerging adjacent treatments that are either under development or so new that need to see if we can get those to our patients in a way that is affordable.

So the impact on disease management is really that physicians can be absolutely specific about the therapy that’s needed for each individual patient. Additionally, it’s not just that we find a mutation and prescribe a particular therapy for that mutation, but that sometimes the absence of mutations is important. For example, immunotherapy is very effective and there’s no particular indication for immunotherapy – anybody with lung cancer is eligible, but we know that patients who have mutations in genes like EGFR or ALK, they really should not receive immunotherapy, they’re not going to do well with those treatments. Hence, some sometimes there’s a negative predictive effect as well. Testing is not just about which treatment a patient should have, but also which shouldn’t have. Also, the appropriate therapy for a patient can change over the course of the disease as well. A patient might start off with an EGFR mutation and then go on to therapy but over the course of their disease we’ll need to recheck as they might have acquired new mutations or become resistant to that the initial therapy. So the impact of biomarker analysis is not only at the beginning of treatment but also over the ensuing months or years as we’ll use that to change and alter the therapy that a patient’s being given as the disease changes.

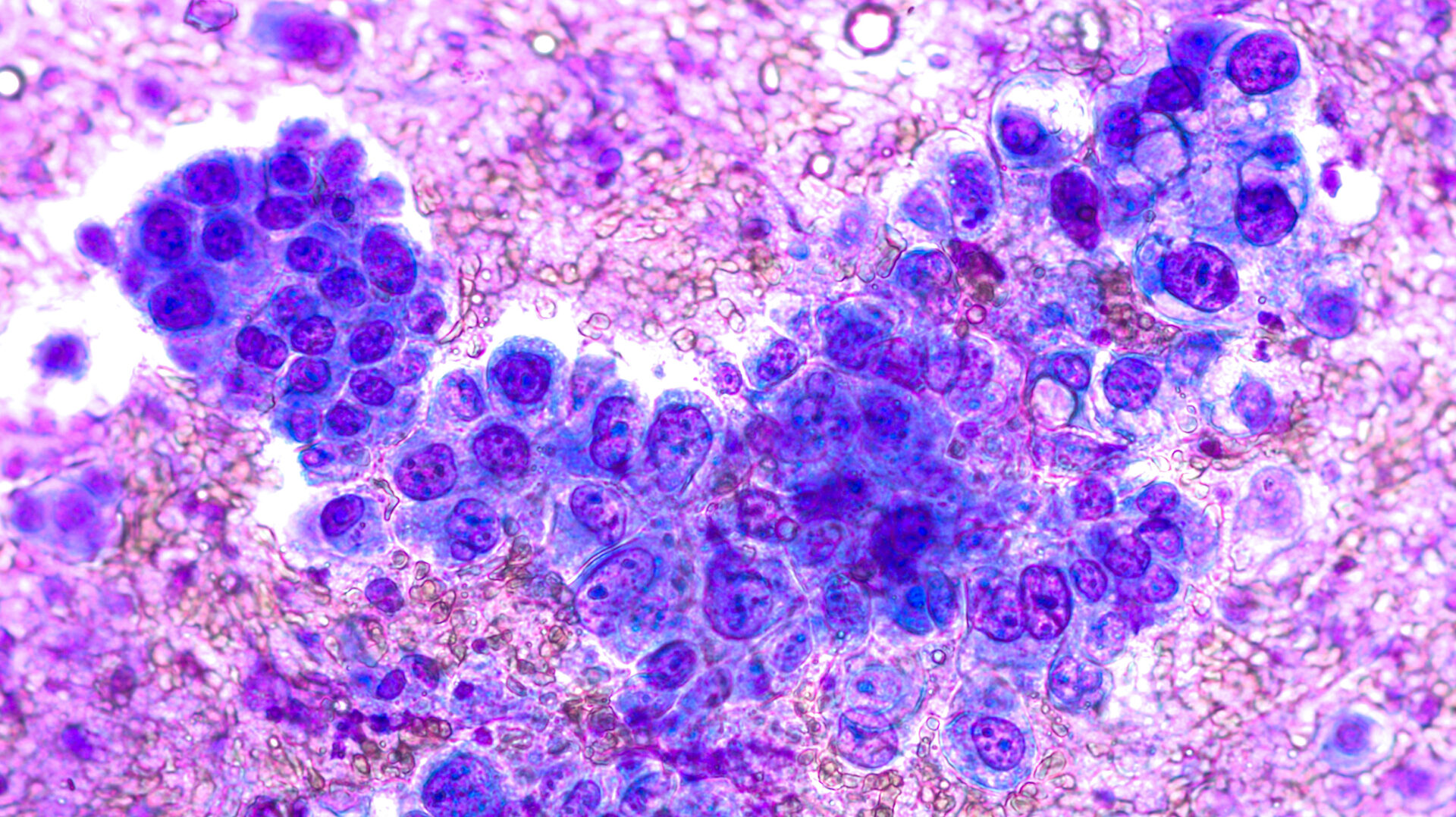

Photomicrograph of fine needle aspiration (FNA) cytology of a pulmonary (lung) nodule showing adenocarcinoma, a type of non small cell carcinoma (David A. Litman, Adobe Stock)

What is external quality control and why is it necessary for the laboratory-based care of NSCLC patients?

So everybody reading this is involved in laboratory medicine in some way and we live in a world where quality is paramount. We need to ensure the results we’re providing are accurate and we do that internally with our own processes. But it’s very important to use external quality services because they see what we don’t see. They expose what we’re blind to and that exact same thing is true for biomarker testing. Historically, when labs or jurisdictions or even whole countries don’t participate in quality assurance or external quality assurance (EQA), we’ve seen disastrous effects when it comes to biomarker testing where entire cohorts and generations of patients might have been given the wrong treatment. For EQA, what we want is an outside agency to deliver samples that are tested in a very similar fashion to patient samples and that will review our results compared to some sort of reference standard and then provide feedback to the lab. So that if they’re drifting away from the results that their peers or that the reference standard is providing they would know about it and be able to perform some sort of corrective action in order to improve that quality. EQA organizations are present around the world – many countries have their own and then many labs will participate in their national service as well as in international services. So, in our lab here at the William Osler Health System we use EQA from Canada, from the US and from Europe. The study that we’re discussing today was performed by the Canadian Pathology Quality Assurance (CPQA) and this organization has been providing biomarker EQA in Canada for over two decades. For those past two decades we’ve really done a lot of biomarker testing for immunohistochemistry (IHC), where antibodies are used to detect proteins in tissue samples, and the results are viewed using a microscope. IHC biomarkers have really led the way in disease sites like breast cancer. However, for lung cancer, a lot of these tests are done by gene sequencing or more molecular methods.

Are EQA schemes sufficient, or is there a better approach?

We have EQA schemes that look purely at the analytics (Is your instrument working properly?) and then there are some that look at other upstream processes like DNA extraction (Are you getting a sufficient amount of DNA out of this sample?) but then not looking really at what we’re doing afterwards. Then there are some that look at reporting as well (Was your report legible and understandable to an oncologist? Does it have all the necessary information?). However, for lung cancer, where there has not really been much of a question about result accuracy, what we have seen in Canada and heard from our colleagues around the world is that when a patient or an oncologist meet each other for the first time that they don’t have those lab reports available to discuss and they have to wait over a month sometimes two months to get those results, knowing that every day they wait there’s a chance of death or deterioration.

So, the CPQA came out with a very novel way of monitoring quality for the samples and for the labs that participated in this study. We designed our EQA to look specifically at the turnaround time. Most existing EQA schemes from the USA and Europe tend to send samples in Eppendorf tubes in the mail and labs will test them to make sure their gene sequencers are finding the KRAS and EGFR mutations and that they’re getting the correct results. We opted instead to send formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) block samples, which is the state in which patient samples exist within hospital laboratories and their archives, and this is usually the state in which a sample would be mailed or shipped to a testing facility. Then there are a couple of steps that a lab would need to go through including sectioning, histology, DNA extraction and others before that sample’s ready to go onto a gene sequencer. Then, once that sample comes off a gene sequencer, there are a number of other steps like interpreting the results, drafting a report and signing it out. So with our CPQA study, we provided an FFPE block which is a very upstream starting material, similar to what a lab would receive in a real scenario, and instead of accepting raw results we asked labs to upload their full report. So they had to take the specimen truly from start to finish and that enabled us to measure the full turnaround time. So, in addition to checking whether the results were correct or not, we measured how long it took labs to do this.

In your recent exercise of proficiency testing for NSCLC biomarker analysis, what were the main findings?

The results were very interesting because in many instances a lab would get the correct result but it might take two months instead of the guideline time of two weeks or less which we observed in some other labs that were a little bit more efficient with their time and with their specimen management. In terms of evaluation, we had a team of oncologists look at the reports – including the turnaround time – and prescribe a therapy based on those. What we found was that it if a lab got the correct results but they took too long that would cause the oncologist to prescribe an incorrect therapy similar to if they had been given the wrong results in the first place. That was a fairly novel finding that we’ve never really seen in lung cancer literature or in quality assurance literature. We’ve heard so often from colleagues all around the world that this is taking so long and but this is this is the first time that we’ve ever had data to back up those claims and testimonials from our end users – our patients and oncologists. We had also sent out a questionnaire associated with the assessment which asked the laboratories to report what they perceived their turnaround time to be and when we compared that to what the measured turnaround time the results had no correlation whatsoever. Nobody – not the fastest lab or the slowest lab – was able to accurately gauge their own turnaround time, which is interesting because actually in most jurisdictions that self-reported metric is what we’re using to monitor lab performance right now, and essentially it’s just a number that’s totally made up. So primarily, we found that labs across Canada would provide different results at different turnaround times and that had a profound impact on treatment selection by medical oncologists. So really the differences in lab performance would lead to big differences in the therapies that patients are receiving and by extension would lead to a big difference in patient outcome. So, key message for the participants, for the audience and for the lung cancer community is that we really do need to pay closer attention to turnaround time. We do need to find a way to help the labs that are working too slowly. We have international and Canadian guidelines saying that samples should be processed and reported on within 14 days but only two of our 14 participating labs were able to meet that. So we know it’s possible but we do need to put some resources and effort in to help make sure that all labs are achieving that. Additionally, we have to make sure that all labs are participating in EQA on a regular basis as over the past three years of doing these exercises we have seen that simply participating makes labs faster – every lab that has participated for more than two sessions in a row has got faster over time.

Another aim was to assess the report to see how understandable it was to the oncologist. In a lot of cases, the result would be correct but the oncologist couldn’t really understand what was written there. And, just as with a turnaround time that is too long, if a report can’t be understood by the person who needs to read it, it was equally as ineffective.

We finished the study by giving each lab a rank and three out of the 14 labs received a grading of ‘very excellent’. Although only two labs met the guideline turnaround time of 14 days, we included a third as their turnaround time was 15 days and additionally all of these labs had very beautiful reports that were succinct and easily understood by oncologists and each of these three labs was able to guide every oncologist to the correct therapy for their patient every single time. We decided, therefore, to take a deeper dive and look at what these three labs doing that the other 11 were not. Interestingly they all use different gene sequencers, different DNA extraction methods – there was nothing in their apparatus or equipment that was common to these labs. However, the one thing that they did have in common was that they were all molecular pathologists (a medical professional who specializes in clinical pathology). This was apparent because there was one single person that signed off on the report and that report had their gene sequencing findings as well as their IHC results. So that one person was looking down the microscope at the IHC samples and at the gene sequencing data and summarized everything into a single report. The labs that went a lot slower did not have that approach. They were using an anatomic pathologist to look at the IHC specimens and they were using that anatomic pathologist to assess the sample when it first came in. Then the specimen was transferred to a different lab that did the more molecular testing, such as the DNA extraction and sequencing. Then there was a separate report signed by usually a PhD scientist. This system caused two things: firstly, the amalgamation of the different results created a report that became very confusing for the end readers but also, secondly, using two different services was much slower and contributed to the increased turnaround time.

The really interesting takeaway for me is that the one of ‘equipment’ that really helps labs go faster is having that molecular pathologist. Molecular pathology is an emerging specialty in Canada – it’s not a very common specialist to find and we don’t train a lot of individuals to be able to do this task within the laboratory. However, certainly from a lung cancer perspective, the study really highlighted how having a molecular pathologist can help tie the whole process together.

Going forward, how do you hope the proficiency testing exercise will improve laboratory practice?

This assessment gives us the opportunity to provide feedback to the labs about what good practice looks like. It gives labs evidence-based data for them to see how they are doing; if they are lapsing below a certain level it gives them the data to go to their administrators to discuss how to improve performance – whether it’s buying new instruments or hiring new staff.

Another thing that was really cool about this study was that we brought our clinicians into it as well. EQA is usually a ‘for the lab by the lab’ endeavour, but in this study the assessors were all medical oncologists and it gave them a chance to see how things work in the lab, which they found fascinating. It was also a really useful experience for them to have seen the different reporting styles, turnaround times and the publications that have come out of the study.

It would be great to be able to transport this all-encompassing, end-to-end EQA scheme to a larger region and the challenges we are working with now are how to make the project easier to deliver on a regular basis and on a wider scope, as it took a lot of time to prepare the samples to make sure that each lab got an identical looking sample without introducing any heterogeneity so that we could ensure that any differences we measured were truly an effect of lab performance. Also, it was a big commitment for the volunteer oncologists to be part of our assessing committee and to review three reports from each of the 14 participating labs when they are busy physicians taking time out of their clinics to do this. It may be that in future we will be able to use artificially engineered samples or an AI tool to help with the report evaluation. This is what we are working on at the CPQA to take this style of proficiency testing to the next level.

The interviewee

Brandon S. Sheffield, MD;

Medical Director

Division of Advanced Diagnostics, William Osler Health System,

Brampton, ON L6R 3J7, Canada

Email: brandon.sheffield@williamoslerhs.ca

For further information see:

Bisson KR, Beharry A, Blais N, Carter MD, Cheema PK, Desmeules P, Garratt JG, Melosky B, Lo B, Snow S, Tessier-Cloutier B, Tio E, Yip S, Won JR, Sheffield BS. novel approach to proficiency testing reveals significant variations in biomarker practice leading to critical differences in lung cancer management. JTO Clin Res Rep 2025;6(7):100837 (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtocrr.2025.100837).