Scientists create lab-grown blood cells from self-organising human embryo models

Scientists at the University of Cambridge have created three-dimensional embryo-like structures from human stem cells that spontaneously produce blood cells, offering a new window into early human development and a potential source of cells for transplantation. The structures, called ‘hematoids’, develop beating heart cells and blood stem cells without requiring the complex cocktails of growth factors typically needed in laboratory settings.

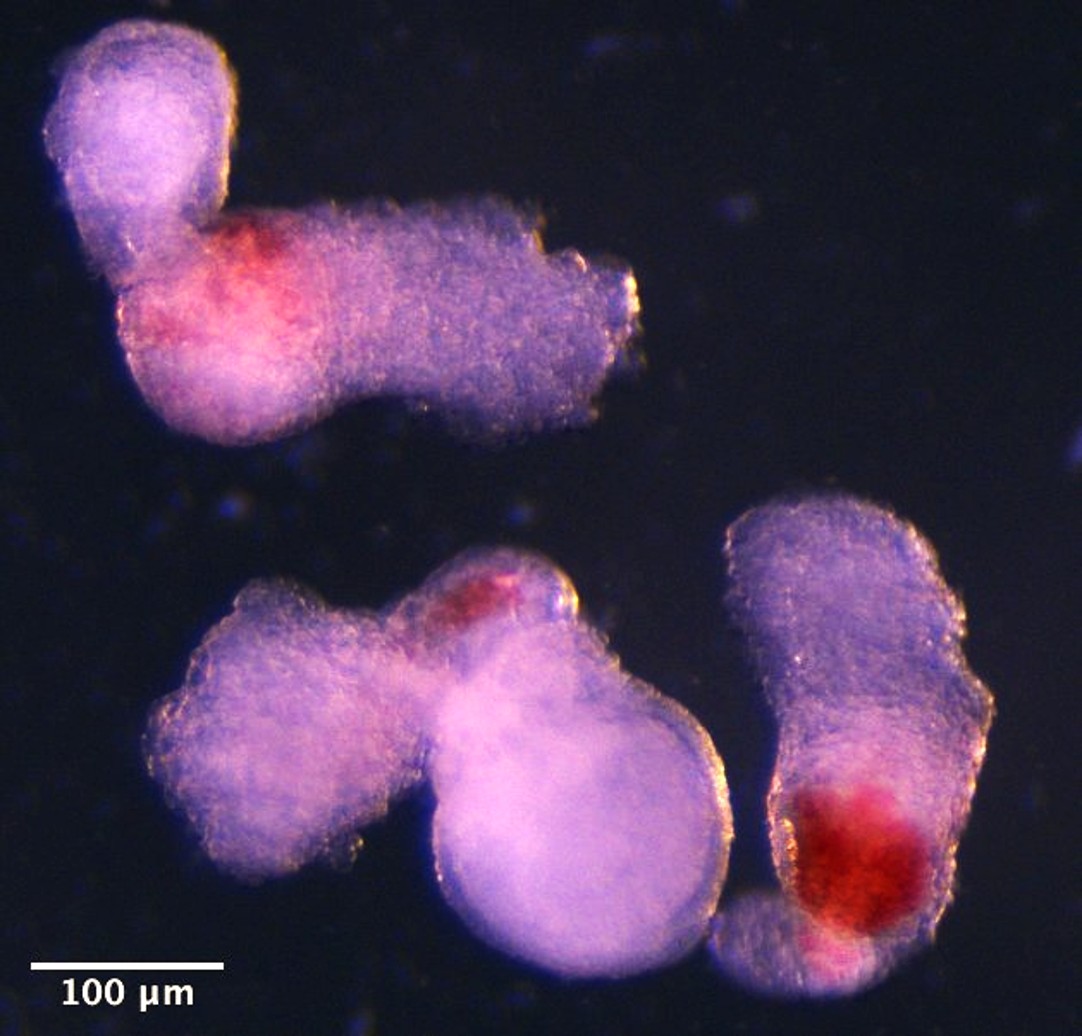

The research team used human pluripotent stem cells to generate structures that replicate aspects of human development between four and six weeks post-conception. By day eight, beating heart cells had formed. By day thirteen, red patches of blood appeared in the hematoids.

Dr Jitesh Neupane, a researcher at the University of Cambridge’s Gurdon Institute and first author of the study, said: “It was an exciting moment when the blood red colour appeared in the dish – it was visible even to the naked eye.”

Self-organising developmental model

The team observed the development of the three-dimensional embryo-like structures under a microscope in the lab. These started producing blood after around two weeks of development, mimicking the development process in human embryos. The structures differ from real human embryos in many ways, and cannot develop into them because they lack several embryonic tissues, as well as the supporting yolk sac and placenta needed for further development.

The researchers employed a kinetic maturation approach, initially culturing cells in static conditions before transferring them to a rotating culture system. This method, combined with inhibition of the TGF-β1 signalling pathway, proved crucial for the development of multiple tissue types.

The resulting structures include cardiomyocytes, hepatocytes, endothelial cells and hematopoietic cells, but they lack a yolk sac. Notably, the researchers observed SOX17+ RUNX1+ hemogenic buds, where they detected the maturation of hematopoietic stem cells. These hemogenic niches, where endothelial-to-haematopoietic transition occurs, contain instructive factors (DLL4, SCF) and restrictive factors (FGF23) for the maturation of HSCs.

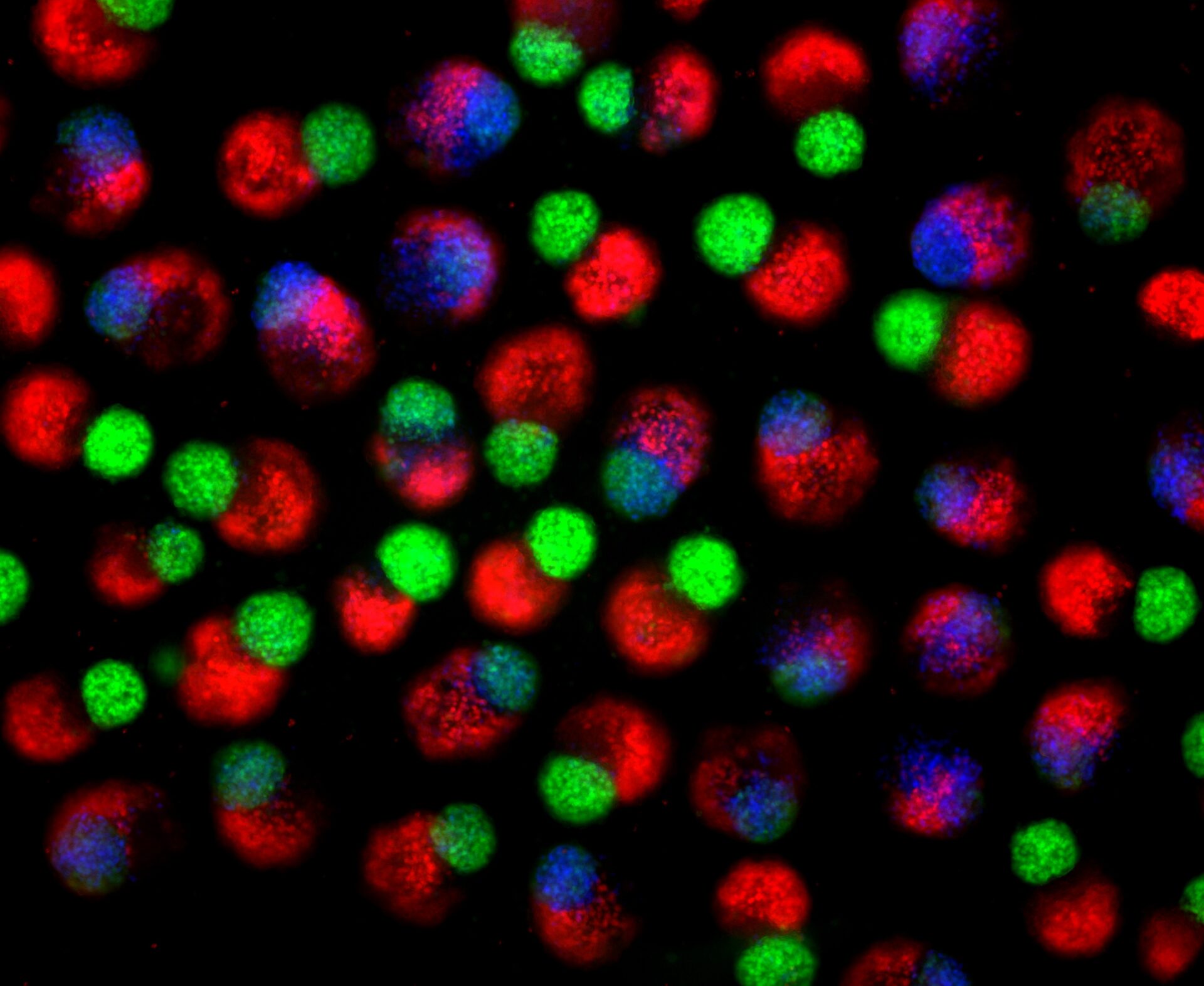

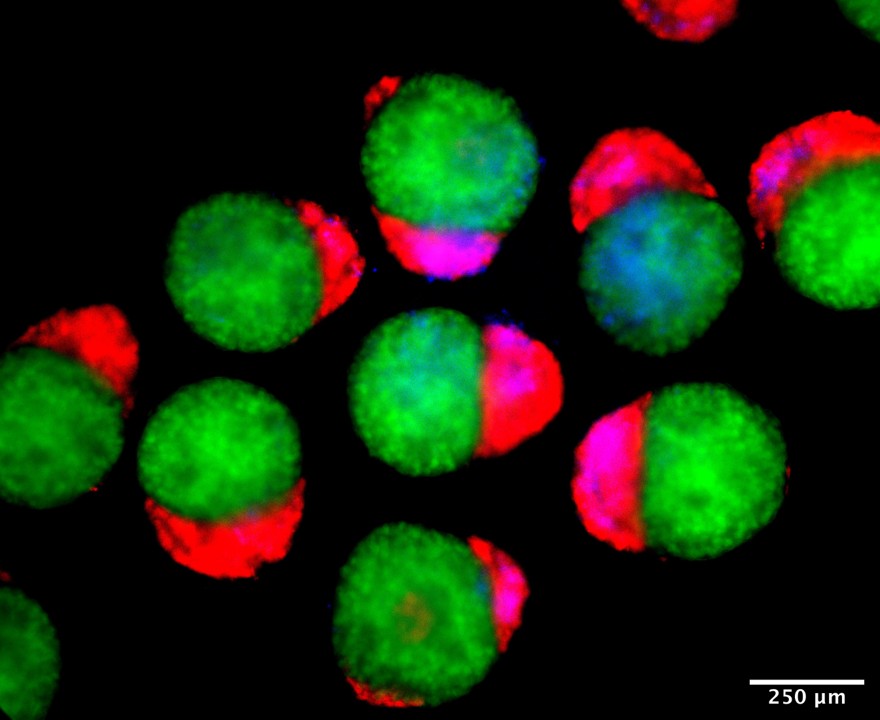

Day 2 hematoids: Human stem cells start to self-organize into three-dimensional clumps establishing primary germ layers, including endoderm (red), ectoderm (green) and mesoderm (blue) derivatives. Primary germ layers give rise to all the tissues and organs of the body.

Definitive blood cell production

The team demonstrated that the blood stem cells produced in hematoids have the potential to differentiate into both myeloid and lymphoid lineages, indicating they represent definitive rather than primitive haematopoiesis. This distinction is crucial, as definitive blood stem cells can generate the full range of mature blood cells needed for therapeutic applications.

Dr Geraldine Jowett at the University of Cambridge’s Gurdon Institute, a co-first author of the study, said: “Hematoids capture the second wave of blood development that can give rise to specialised immune cells or adaptive lymphoid cells, like T cells opening up exciting avenues for their use in modelling healthy and cancerous blood development.”

The team developed a method which demonstrated that blood stem cells in hematoids can differentiate into various blood cell types, including specialised immune cells, such as T-cells. The blood cells in hematoids develop to a stage that roughly corresponds to week four to five of human embryonic development. Professor Azim Surani at the University of Cambridge’s Gurdon Institute, senior author of the paper, said: “This model offers a powerful new way to study blood development in the early human embryo. Although it is still in the early stages, the ability to produce human blood cells in the lab marks a significant step towards future regenerative therapies – which use a patient’s own cells to repair and regenerate damaged tissues.”

Day 4 hematoids displaying derivatives of the three germ layers – ectoderm (green), mesoderm (blue), and endoderm (red) – that establish the foundation of the human body.

Endogenous niche factors

A particularly significant finding was that the hemogenic niche in hematoids produces its own supportive factors, eliminating the need for exogenous cytokine supplementation typically required in embryoid body-based approaches. The researchers identified distinct SOX17+ RUNX1+ hemogenic buds within the structures that closely resembled regions found in the aorta-gonad-mesonephros of human embryos.

The timing of TGF-β1 inhibition proved critical. When inhibition occurred too early in development, the structures failed to produce blood cells despite containing endothelial cells, demonstrating the importance of precise temporal control in directing cell fate decisions.

The structures lack many tissues and should not be assigned a Carnegie stage themselves, but day 14 clusters mapped to the transcriptome and cell-type composition of Carnegie stage 12–16 human embryos. This finding demonstrates that rotary cultures under TGF-β1 inhibition substantially progressed the model beyond gastrulation.

The scientists have patented this work through Cambridge Enterprise, the innovation arm of the University of Cambridge. The research was supported by funding from the Human Development Biology Initiative, with the Gurdon Institute receiving core support from Wellcome Trust and Cancer Research UK.

The study was published in Cell Reports on 13 October 2025.

Reference:

Neupane, J., Jowett, G. M., Wu, B., et. al. (2025). A post-implantation model of human embryo development includes a definitive hematopoietic niche. Cell Reports, 116373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2025.116373

Day 14 hematoids developing visible red patches where blood is forming.