Measuring infliximab and adalimumab drug and antibodies in Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis

The anti-TNF therapies infliximab and adalimumab have revolutionized the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease, being very effective in many patients. Some patients experience problems such as loss of response, which is associated with production of antibodies to the therapy. Measuring trough drug and antibody concentrations may direct patient management in future.

by Dr Mandy Perry, Dr Tim McDonald, Adrian Cudmore, Dr Tariq Ahmad

Ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD) are relapsing and remitting inflammatory disorders of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Recently published data suggests that as many as 620 000 people in the UK could have these inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs). Both conditions can produce symptoms of urgent and frequent diarrhea, rectal bleeding, pain, profound fatigue and malaise. In some patients, there is an associated inflammation of the joints, skin, liver or eyes. Malnutrition and weight loss are common, particularly in CD. These conditions can cause considerable disruption to education, working, social and family life. There is currently no cure. Drugs to suppress the immune system are the mainstay of medical management, and first line treatment typically includes corticosteroids, with immunmodulators such as azathioprine, mercaptopurine or methotrexate used for patients with steroid-dependent disease. However, 30% of patients either fail to respond, or are intolerant, to these drugs and will then be considered for biological therapies or surgery. More than half of patients with CD and about 20–30% of patients with UC will require surgery at some point. The anti-TNF agents infliximab and adalimumab have revolutionized treatment of IBD, and are an effective alternative to surgery, leading to complete remission in many patients [1].

NICE has published guidelines for the use of anti-TNF agents for CD [2] and UC [3]. These drugs include the monoclonal anti-TNF drugs infliximab (includes the original product – Remicade, and biosimilar infliximab Remsima and Inflectra) and adalimumab (Humira). TNF is a cytokine involved in systemic inflammation and the anti-TNF drugs bind to and inactivate TNF, thereby halting the immune cascade and reducing inflammation. Infliximab is a mouse–human chimeric anti-human TNF antibody which is administered by intravenous infusion with a typical induction course of therapy at weeks 0, 2, 6 and then 8-weekly maintenance dose. Adalimumab is a fully human anti-human TNF antibody, and is administered by subcutaneous injection every 2 weeks. For some patients this is a more convenient option, as the subcutaneous rather than intravenous administration means that frequent hospital appointments are not required. Both infliximab and adalimumab are expensive treatments, typically costing in excess of £10,000 per annum. The 2015 introduction of biosimilar infliximab preparations has significantly reduced the price of therapy.

Some patients have an excellent response to anti-TNF treatment, managing to obtain complete remission of CD and mucosal healing. However, a proportion of patients do not respond well to anti-TNF therapy [4], and there are three principal problems:

- Primary non-response (PNR): no response in the first instance of starting the drug

- Loss of response (LOR): following an initial good response to the drug, this is lost and CD returns

- Adverse drug reactions (ADR).

The etiology of these problems is unknown, although the following causes have been indicated [1]:

- Primary non-response – has sufficient drug concentration been achieved?

- Loss of response – commonly caused by development of antibodies to the drug, which increases clearance and decreases in vivo half-life.

- Adverse drug reactions – infusion reactions are associated with formation of antibodies to the drug [5].

Approximately 25% of patients will develop antibodies to infliximab and adalimumab drugs within 12 months of treatment initiation. The clinical importance of such antibodies is not completely understood. It is hypothesized that anti-drug antibodies may alter the action of the drug (i.e. neutralizing) and/or increase the drug clearance (i.e. non-neutralizing). Antibodies may be transient (and may be ‘overcome’ by increasing the concentration of drug), or persistent (and intolerant of drug escalation) [6, 7].

Measuring drug and anti-drug antibodies may enable problems such as ADR, PNR and LOR to be further understood, and may assist clinicians in the management of these problems. Possible interventions include escalating the dose of anti-TNF therapy, adding in an additional drug (e.g. immunomodulator or steroid), switching to an alternative anti-TNF therapy or switching to a non-TNF biologic.

For infliximab, several algorithms for patient management have been developed using drug and antibody levels [8, 9]. Several different assays, using different therapeutic ranges have been employed as part of these algorithms, making comparison difficult. The widely quoted TAXIT (Trough level Adapted infliXImab Treatment) trial uses a therapeutic range for infliximab of 3–7 mg/L [8], whereas work by Steenholdt uses 5–10 mg/L [9]. The different technologies used to measure drug and anti-drug antibodies, include ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay), HMSA (homogeneous mobility shift assay) [10], radioimmunoassay, and a functional cell-based reporter gene assay [11]. There is poor agreement between the drug assays, as there is neither gold standard material, nor a reference method available.

Clinicians and laboratories should also be aware that there is considerable variation in what is being measured for the antibody assays. For example, the ELISA antibody assays either measure free (i.e. only those antibodies which are not bound to drug in the patient serum) or total antibodies (i.e. bound and unbound to drug). The functional cell-based assay is different again, as it is designed to detect only those antibodies which prevent infliximab from binding to TNF and therefore may not detect antibodies that are postulated to alter the drug clearance only. Although anti-TNF drug and antibody testing shows promise, there is not yet sufficient cost-effective data, nor diagnostic algorithms, for widespread adoption across the NHS. It seems likely that use in the setting of loss of response will enter clinical practice first and may allow cost savings by avoiding dose escalation in patients with high levels of antibodies.

The Personalized Anti-TNF Therapy in Crohn’s disease (PANTS) study is a prospective, observational study for which anti-TNF naïve patients aged 6 and over are eligible. The study aims to investigation the clinical, serological and genetic factors that determine PNR, LOR and ADR to anti-TNF drugs in patients with active luminal Crohn’s disease. The study is recruiting from over 110 UK hospitals currently participating in the UK Inflammatory Bowel Disease Genetics Consortium pharmacogenetic programme. While attending routine clinical appointments, additional information and samples are collected for the PANTS project. This includes the Harvey Bradshaw index (HBI, a scoring system which classifies recent disease in terms of symptoms), blood for DNA, RNA, CRP (C-reactive protein), anti-TNF drug and antibody levels and stool samples for calprotectin. Analysis of CRP, calprotectin and anti-TNF alpha drug and antibody levels is undertaken at the Central Laboratory at Exeter Blood Sciences Laboratory, where a biobank of additional serum aliquots is being constructed. Infliximab and adalimumab drug levels, total anti-infliximab antibody and total anti-adalimumab antibody are measured by ELISA technology (Immundiagnostik), using a liquid handling robot (DS2, DYNEX Technologies) [12]. Biochemical data is uploaded onto a bespoke web-based database that is also used to store the clinical information.

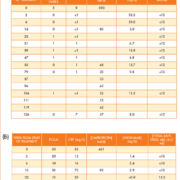

Examples of data for two patients from the PANTS study are shown in Table 1. Table 1A is data from a patient who is prescribed infliximab. Week 0 shows baseline data before treatment with infliximab. The calprotectin is raised, indicating active inflammation, and this is mirrored with the CRP and Harvey Bradshaw Index (HBI score of <5 indicates remission; 5–7 mild disease, 8–16 moderate disease and >16 severe disease). By week 14, the calprotectin has decreased substantially, and the CRP and HBI have decreased to normal values at week 2. Until the end of the timeframe (week 126), the patient continues to have a normal calprotectin, CRP and HBI. The drug level concentration in the maintenance phase is between 3–14 mg/L and the patient remains negative for anti-drug antibodies (i.e. <10 AU/mL). Table 1B shows data from a pediatric patient who is prescribed infliximab. The PCDAI (Pediatric Crohn’s Disease Activity Index) is used in place of the HBI. When infliximab naïve (week 0), the patient had a raised CRP, calprotectin and PCDAI (<10 remission; 10–29 mild disease; 30–39 moderate disease; >40 severe disease). Upon treatment with infliximab there was initially a good response, shown by the decrease in CRP and PCDAI. At week 22, the patient became positive for anti-drug antibodies and the trough drug concentration became undetectable. At week 26, the patient had clinical loss of response and underwent surgery. Knowledge of the patient’s drug and antibody levels helps with clinical management in the setting of loss of response, such as in this case. Dose escalation is likely to be futile and costly in patients with high antibody titres. Switching to an alternative anti-TNF might provide transient benefit, although patients who form antibodies to one anti-TNF are likely to form antibodies to the second and subsequent agents in this class.

The anti-TNF drugs infliximab and adalimumab are effective treatment for CD in many patients. However, LOR, PNR and ADR are significant problems, and it is so far unclear as to how these patients should be best managed. Measuring drug and antibody concentrations may allow for diagnostic algorithms to be produced. The clinical and cost effectiveness of therapeutic monitoring of TNF inhibitors using ELISA technology is currently being evaluated by NICE [13]. It is anticipated that data from the PANTS study will directly inform such algorithms and guidelines, and contribute to an evidence based medicine approach for management of CD patients who are prescribed anti-TNF therapy.

References

1. Vande Casteele N, Feagan BG, Gils A, et al. Therapeutic drug monitoring in inflammatory bowel disease: current state and future perspectives. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2014; 16: 378.

2. NICE technology appraisal guidance [TA187]. Infliximab (review) and adalimumab for the treatment of Crohn’s disease. NICE 2010. (https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta187/chapter/1-guidance).

3. NICE technology appraisal guidance [TA329]. Infliximab, adalimumab and golimumab for treating moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis after the failure of conventional therapy (including a review of TA140 and TA262). NICE 2015. (https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta329)

4. Nielsen OH, Seidelin JB, Munck LK, Rogler G. Use of biological molecules in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. J Int Med. 2011; 270: 15–28.

5. Vande Casteele N, Ballet V, Van Assche G, et al. Early serial trough and antidrug antibody level measurements predict clinical outcome of infliximab and adalimumab treatment. Gut 2012; 61: 321.

6. Hanauer S, Feagan B, Lichtenstein G, et al. Maintenance infliximab for Crohn’s disease: the ACCENT I randomised trial. Lancet 2002; 359: 1541–1549.

7. Cornillie F, Hanauer B, Diamond R, et al. Postinduction serum infliximab trough level and decrease of C-reactive protein level are associated with durable sustained response to infliximab: a retrospective analysis of the ACCENT I trial. Gut 2014; 63; 1721–1727.

8. Vande Casteele N, Ferrante M, Van Assche G, et al. Trough concentrations of infliximab guide dosing for patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 2015; 148: 1320-1329.

9. Steenholdt C, Brynskov J, Thomsen OØ, et al. Individualised therapy is more cost-effective than dose intensification in patients with Crohn’s disease who lose response to anti-TNF treatment: a randomised, controlled trial. Gut 2014; 63: 919–927.

10. Wang SL, Ohrmund L, Hauenstein S, et al. Development and validation of a homogeneous mobility shift assay for the measurement of infliximab and antibodies-to-infliximab levels in patient serum. J Immunol Methods 2012; 382: 177–188.

11. Lallemand C, Kavrochorianou N, Steenholdt C, et al. Reporter gene assay for the quantification of the activity and neutralizing antibody response to TNFα antagonists. J Immunol Methods 2011; 373: 229–239.

12. Perry M, Bewshea C, Brown R, et al. Infliximab and adalimumab are stable in whole blood clotted samples for seven days at room temperature. Ann Clin Biochem. 2015; doi: 10.1177/0004563215580001.

13. NICE. Crohn’s disease – Tests for therapeutic monitoring of TNF inhibitors (LISA-TRACKER ELISA kits, TNFa-Blocker ELISA kits, and Promonitor ELISA kits). Anticipated publication date: December 2015. (https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/indevelopment/gid-dt24/consultation/crohns-disease-tests-for-therapeutic-monitoring-of-tnf-inhibitors-lisatracker-elisa-kits-tnfablocker-elisa-kits-and-promonitor-elisa-kits-consultation)

The authors

Mandy Perry*1 PhD, Tim McDonald1 FRCPath. PhD, Adrian Cudmore1, Tariq Ahmad2 MB ChB, DPhil, MRCP(UK)

1Department of Blood Sciences, Royal Devon and Exeter NHS Foundation Trust, Exeter, UK

2IBD Pharmacogenetics Research, University of Exeter, Exeter, UK

*Corresponding author

E-mail: mandy.perry@nhs.net