There are promising results regarding the use of antibodies for the diagnosis of cervical cancer (CC). This article reviews the antibody response against HPV proteins during the development of the disease as well as their possible use as biomarkers for the progression of cervical lesions and of CC.

by Dr D. A. Salazar-Piña, Berta A. Carrillo-Quiroz and Dr L. Gutierrez-Xicotencatl

Introduction

Cervical cancer (CC) has been a major public health problem among adult women, especially in developing countries. According to the WHO (Word Health Organization) GLOBOCAN project, in 2012 alone, there were more than 440 000 incident cases of CC and over 230 000 deaths due to the disease. Several studies have shown that high-risk (HR) human papillomavirus (HPV) types are important risk factors for the development of CC, and the most common types associated with this disease are HPV-16 and -18 [1].

Initial infection with HPV involves access of viral particles to the basal cell layer of the transform zone of the uterine cervix, which allows viral proliferation through differentiation of the stratified epithelium. During HPV infection, the virus uses cellular mechanisms of the host cell to express essential proteins (E1, E2, E4, E5, E6, E7) for the regulation of the cell cycle and replication of the viral DNA that is then encapsulated in viral particles formed by L1 and L2 capsid proteins [2]. For many years, several groups have studied the different viral proteins to understand the disease, which is caused by persistent infection with HR-HPV.

The HR-HPV types 16 and 18 mainly induce persistent infections without frequent serious complications for the host, and they are highly successful in releasing viral particles transmissible to others. This virus takes the host to a point of balance where the infection does not represent a serious drawback and viral replication is not limited by the host’s immune response because the virus does not have a blood-borne phase or viremia, which allows the HPV infection to persist for a longer period. Under these conditions, it takes a long time for the HPV infection to produce signs of damage to alert the immune system to generate an efficient response to eliminate the infection. Most of these HPV-associated genital lesions are cleared because of a successful cell-mediated immune response, during which cells of the innate immune system (such as keratinocytes, dendritic cells, Langerhans cells, macrophages, natural killer, and natural killer T cells) promote a pro-inflammatory process and eliminate the infection [3].

Diagnosis of cervical cancer

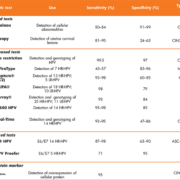

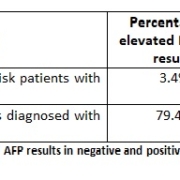

For several decades, actions against this public health problem have been taken in the aspects of prevention, diagnosis and treatment. The use of the Papanicolaou (Pap) smear, which is the primary diagnostic test in most cancer prevention programmes in developed countries, has helped to reduce the global burden of CC, but this has not been the case in developing countries. The main problem is the low and variable sensitivity of the Pap test (50–84%), which makes the identification of premalignant lesions difficult (Table 1) [4, 5]. Among the most frequent complications that the health sector faces is the lack of qualified personnel for sampling, transport, processing and proper evaluation, besides other limitations of the test. More recently, the HPV DNA test has emerged as a good candidate to replace the cytological test. The DNA test has a very high sensitivity for the detection of precancerous lesions (90–100%), but low specificity (47–80%), which makes this test suitable for screening [6]. However, the presence of HPV DNA is not indicative of an active infection; therefore, it has been necessary to develop new diagnostic systems to evaluate progression to CC. Hence, diagnostic systems of greater sensitivity and specificity are needed in order to detect the disease earlier and to prevent the development of CC.

In the newly developed tests for detecting early stages of the disease, the direct detection of HPV E6/E7 proteins, carried out in cell scrapes or cervical tissue samples, has shown low sensitivity as less than 1% of the cells are infected and express the oncogenic proteins. Another test is the surrogate marker p16 that is overexpressed in CC and is an indirect marker of the expression of the HPV E7 oncoprotein [7]. Although these tests have high specificity, unfortunately they still depend on a tissue sample or a cervical lavage, in which the number of HPV-infected cells is reduced (<1%), making it difficult to identify real patients at risk of developing CC [8].

Serological biomarkers for diagnosis of CC

There is, therefore, still a need to look for a test or a combination of tests that are highly sensitive and specific, and less invasive for the detection of early lesions of the uterine cervix that are progressing to CC. Thus, anti-HPV serum antibodies have become a good alternative new biomarker for the detection of CC-associated premalignant lesions. The humoral immune response is a naturally amplified system that allows the detection of low viral antigen concentrations in patients at risk to develop CC associated with persistent HPV infection. The potential of anti-HPV antibodies as biomarkers for CC is because the sequential expression of early HPV proteins in the uterine cervix correlates with the serological data and this might be useful for the identification of previous, current and persistent infections that could be related to the progression of the disease.

The specific antibody response against HPV antigens has been used, first as a method to study the biology of the HPV; later on, it was used to evaluate the efficacy of the new HPV vaccines, and more recently, a possible use as biomarkers of HPV-associated cancers at different anatomical sites has been proposed. Different groups have studied the antibody response against early and late HPV proteins and mixed results have been reported, a variability that could be attributed to the use of different type, purity and source of antigens, as well as the different assays used (Western blot, ELISA, multiplex, slot blot) (Table 2) [9]. However, there are promising studies that combine different viral antigens as new biomarkers for the early detection and progression of HPV-associated CC. For instance, antibodies against HPV16 E6/E7 proteins have predominantly been found in patients with advanced CC (75–80%), and they have been suggested as markers for CC [10]. Antibodies against the VLP L1 protein have shown to be useful to detect new HPV infections in women that initiate sexual life [11], as well as to detect women at risk of developing cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 (CIN3) and CC [12], or associated with the clearance of the HPV infection [13]. Similarly, anti-E4 antibodies have been associated with premalignant lesions (CIN1–2), and because the E4 protein has been implicated in early stages of viral replication, it has been suggested to be useful as an early marker for CIN1–2 lesions [14].

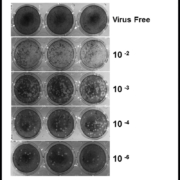

More recently, a new slot blot system has been used to analyse the presence of antibodies against E4, E7 and L1 proteins, and it was shown that anti-E4 and anti-E7 antibodies were highly associated with women with CC. The clinical performance of the slot blot system for the anti-E4 and/or anti-E7 antibodies was very good to discriminate CC from CIN2–3 with a high sensitivity (93.3%) and moderate specificity (64.1%). These findings suggest that these anti-E4 and anti-E7 antibodies could be used as biomarkers to distinguish pre-neoplastic lesions from CC [15]. Nevertheless, despite the scientific evidence, prospective studies need to be carried out to determine the usefulness of these antibodies as early markers and/or predictors of disease.

Conclusions

The diagnostic systems used for the detection of uterine cervical lesions, such as the Pap test and colposcopy, detect the disease at very late stages. The introduction of HPV DNA detection as a screening test has increased the identification of high-grade lesions, but it has still not been enough to distinguish an active infection that could progress to CC, especially because these premalignant lesions can undergo regression in around 70% of the cases. In order to increase the sensitivity and specificity of detecting women at risk of developing CC, a combination of tests has been suggested. In this scheme, the new serological biomarkers (anti-E4 and anti-E7 antibodies), which have shown to associate with CC and to discriminate it from premalignant lesions, could be used after or in co-testing with the Pap test to discriminate the false negatives of the Pap test from the real CC cases. It is expected that the combination of different tests such as the Pap test, HPV-DNA detection and the serological tests could help to detect over 85% of the CC cases that are missed when only one test is performed. More prospective studies with a larger panel of HPV antigens to evaluate other HPV antibodies need to be carried out to determine the usefulness of these antibodies as biomarkers for the detection and prediction of CC-associated premalignant lesions.

References

1. Faridi R, Zahra A, Khan K, Idrees M. Oncogenic potential of human papillomavirus (HPV) and its relation with cervical cancer. Virol J. 2011; 8: 269.

2. Doorbar J. The papillomavirus life cycle. J Clin Virol. 2005; 32(Suppl 1): S7–15.

3. Stanley MA, Sterling JC. Host responses to infection with human papillomavirus. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2014; 45: 58–74.

4. Hegde D, Shetty H, Shetty PK, Rai S. Diagnostic value of acetic acid comparing with conventional Pap smear in the detection of colposcopic biopsy-proved CIN. J Cancer Res Ther. 2011; 7(4): 454–458.

5. Gutiérrez-Xicotencatl L, De la Fuente-Villarreal D, Astudillo-de la Vega H. Biología molecular en el diagnóstico del cáncer cervicouterino asociado a pailomavirus humano. Gaceta Mexicana de Oncología 2014; 13(Supl 4): 25–32 (in Spanish).

6. Tao K, Yang J, Yang H, Guo ZH, Hu YM, Tan ZY, et al. Comparative study of the Cervista and hybrid capture 2 methods in detecting high-risk human papillomavirus in cervical lesions. Diagn Cytopathol. 2014; 42(3): 213–217.

7. Carozzi F, Gillio-Tos A, Confortini M, Del Mistro A, Sani C, De Marco L, Girlando S, Rosso S, Naldoni C, et al. NTCC working group. Risk of high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia during follow-up in HPV-positive women according to baseline p16-INK4A results: a prospective analysis of a nested substudy of the NTCC randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013; 14(2): 168–176.

8. Gutierrez-Xicotencatl L, Plett-Torres T, Madrid-Gonzalez CL, Madrid-Marina V. Molecular diagnosis of human papillomavirus in the development of cervical cancer. Salud Publica Mex. 2009; 51(Suppl 3): S479–488.

9. Gutierrez-Xicotencatl L, Salazar-Pina DA, Pedroza-Saavedra A, Chihu-Amparan L, Rodriguez-Ocampo AN, Maldonado-Gama M, Esquivel-Guadarrama FR. Humoral immune response against human papillomavirus as source of biomarkers for the prediction and detection of cervical cancer. Viral Immunol. 2016; 29(2): 83–94.

10. Jochmus I, Bouwes Bavinck JN, Gissmann L. Detection of antibodies to the E4 or E7 proteins of human papillomaviruses (HPV) in human sera by western blot analysis: type-specific reaction of anti-HPV 16 antibodies. Mol Cell Probes 1992; 6(4): 319–325.

11. Kjaer SK, van den Brule AJ, Paull G, Svare EI, Sherman ME, Thomsen BL, Suntum M, Bock JE, Poll PA, Meijer CJ. Type specific persistence of high risk human papillomavirus (HPV) as indicator of high grade cervical squamous intraepithelial lesions in young women: population based prospective follow up study. BMJ 2002; 325(7364): 572.

12. Wang ZH, Kjellberg L, Abdalla H, Wiklund F, Eklund C, Knekt P, Lehtinen M, Kallings I, Lenner P, et al. Type specificity and significance of different isotypes of serum antibodies to Human Papillomavirus capsids. J Inf Dis. 2000; 181(2): 456–462.

13. Bontkes HJ, de Gruijl TD, Walboomers JM, Schiller JT, Dillner J, Helmerhorst TJ, Verheijen RH, Scheper RJ, Meijer CJ. Immune responses against human papillomavirus (HPV) type 16 virus-like particles in a cohort study of women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. II. Systemic but not local IgA responses correlate with clearance of HPV-16. J Gen Virol. 1999; 80(Pt 2): 409–417.

14. Vazquez-Corzo S, Trejo-Becerril C, Cruz-Valdez A, Hernandez-Nevarez P, Esquivel-Guadarrama R, Gutierrez-Xicotencatl Mde L. [Association between presence of anti-Ras and anti-VPH16 E4/E7 antibodies and cervical intraepithelial lesions]. Salud Publica Mex. 2003; 45(5): 335–345 (in Spanish).

15. Salazar-Pina DA, Pedroza-Saavedra A, Cruz-Valdez A, Ortiz-Panozo E, Maldonado-Gama M, Chihu-Amparan L, Rodriguez-Ocampo AN, Orozco-Fararoni E, Esquivel-Guadarrama F, Gutierrez-Xicotencatl L. Validation of serological antibody profiles against human papillomavirus type 16 antigens as markers for early detection of cervical cancer. Medicine 2016; 95(6): e2769.

16. Pedroza-Saavedra A, Cruz A, Esquivel F, De La Torre F, Berumen J, Gariglio P, Gutiérrez L. High prevalence of serum antibodies to Ras and type 16 E4 proteins of human papillomavirus in patients with precancerous lesions of the uterine cervix. Arch Virol. 2000; 145(3): 603–623.

The authors

D. Azucena Salazar-Piña1 PhD, Berta A. Carrillo-Quiroz2 MSc, Lourdes

Gutierrez-Xicotencatl*3 PhD

1School of Nutrition, Autonomous

University of Morelos State (UAEM),

Cuernavaca, Morelos, Mexico

2Center of Information for Decisions in Public Health, National Institute of Public Health, Cuernavaca, Morelos, Mexico

3Center for Research on Infectious Diseases, National Institute of Public Health,

Cuernavaca, Morelos, Mexico

*Corresponding author

E-mail: mlxico@insp.mx