Unanswered questions about testing for low testosterone in men

Testosterone is a steroid hormone that develops and maintains the primary and secondary sex characteristics in men. In recent years, there has been an explosive increase in prescriptions for testosterone replacement therapy (TRT) in adult men who are thought to have adult-onset hyopgonadism. This increase has been fueled by changing demographics and by increased public awareness of so-called “low-T” syndrome. Despite recent controversies about risks for cardiovascular complications in men receiving TRT, the trend of increased testing and treatment for low-T is likely to continue. This article explores current controversies and unanswered questions regarding testing for low-T in men. Topics covered include variations in reference intervals for testosterone and thresholds for interpretation of results. Controversies and questions surrounding testing for free (unbound) testosterone will also be explored. Finally, the emerging evidence regarding the roles of dihydrotestosterone and estradiol will be discussed in the context of testing for low-T.

by Dr Michael Samoszuk

Testosterone metabolites include estradiol (produced by the aromatase enzyme found in fat and other tissues such as testes) and dihydrotestosterone (DHT)-an androgenic hormone that is approximately three- to ten-times more potent than testosterone. DHT is produced from testosterone by 5-alpha reductase, an enzyme that is found primarily in hair follicles, prostate, testes, and adrenal glands but not in skeletal muscle.

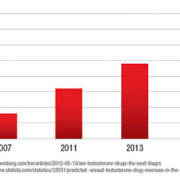

In recent years, there has been an explosive increase in prescriptions (Figure 1) for testosterone replacement therapy (TRT) in men who are thought to have adult onset hypo-gonadism, a condition that is often referred to as “low-T”. This condition is characterized by a variety of signs and symptoms, including loss of body hair, accumulation of visceral and body fat, loss of skeletal muscle, anemia, mood disturbances, loss of libido, and erectile dysfunction. Because of changing demographics and increased awareness of low-T due to marketing campaigns, it is likely that testing for (and treatment of) low-T will continue to increase significantly in the next five years. This increased testing and treatment for low-T will probably occur despite recent controversies about the cardiovascular risks that may be associated with TRT.

How should total testosterone levels be interpreted in men being tested for low-T?

There is considerable variation in the reference intervals for total testosterone assays that are produced by various manufacturers of in vitro diagnostics (Table 1). It is notable that the reference intervals are based on the range of values between the 5th-95th percentiles of men of various ages. Because the populations of men that were used to derive these reference intervals are poorly defined with respect to age distribution and possible symptoms of low-T, it is unclear if these reference intervals provide a reliable basis for interpreting test results from men being tested for low-T. Of particular concern are the lower limits of the reference intervals, which may be too low to identify the significant proportion of men who are truly hypo-gonadal but whose total testosterone levels fall above the 5th percentile of the reference range.

Reference intervals for total testosterone levels reported by reference laboratories also have considerable variation (Table 2). The variation is of particular concern at the low end of the reference interval because many clinicians use this value to determine whether or not a man should be diagnosed as having low-T. Unanswered questions regarding the use of reference intervals that are reported by clinical laboratories include:

- Should the interpretation of these ranges include a consideration of the age of the patient?

- Does a fasting specimen yield a different result from a non-fasting specimen?

- How significant is the effect of time of specimen collection on the total T level?

- Did the determination of reference intervals exclude or include men who may have had low-T even though they were otherwise healthy?

An emerging way to interpret total testosterone levels in men is to use a clinical threshold (cut-off) value for the level. Although there are significant differences in the definitions of the clinical thresholds (Table 3), it appears that the clinical threshold for diagnosing low-T probably lies somewhere between 300-500 ng/dL. Notably, this range lies considerably above the 5th percentiles for testosterone values that are listed in Tables 1 and 2. It should also be noted that all sources of the clinical thresholds listed in Table 3 also recommend the primacy of clinical signs and symptoms when interpreting total testosterone values.

Unanswered questions regarding the use of clinical threshold values are:

- Is there an optimal cut-off value?

- Does the threshold value vary by age of patient?

- What criteria should be used to establish an optimal cut-off value?

- Can a threshold value reliably identify those men who are most likely to experience relief of symptoms with TRT?

- How should threshold values be used and interpreted in the

- context of the patient’s clinical signs and symptoms?

Should free testosterone be measured?

Testosterone circulates in the blood in a free (unbound) form and a bound form. Sex-hormone binding globulin (SHBG) and albumin are the primary sources of binding of testosterone.

Approximately 2% of total testosterone circulates in the free form. Current thinking is that the free testosterone is mostly responsible for the biological activity of the hormone, and the bound form is thought to be mostly inactive. The free and bound forms can be directly measured by a variety of methods, or a mathematical formula can be used to calculate the percentage of free testosterone, based on the values for total testosterone, SHBG and albumin.

There is substantial confusion over the best way to determine free testosterone and how to interpret the results. Unanswered questions include:

- What is the best way to measure free testosterone?

- Is measurement superior to calculated values?

- How should the free testosterone value be interpreted?

- Does free testosterone add any incremental value to the diagnosis of low-T?

Is there a role for testing for DHT?

Testing for DHT is not commonly performed in the evaluation of men being evaluated or treated for hypo-gonadism. At this time, it is not clear how to interpret the test results. There is some evidence, however, that treatment of low-T with topical testosterone preparations can sometimes preferentially elevate the DHT levels due to the presence of 5-alpha reductase in skin and hair follicles. In theory, this phenomenon could account for so-called treatment failures of men who receive topical therapy. It is likely that as our understanding of TRT improves, there will be an increased interest in clinical testing for this metabolite of testosterone.

Is it necessary or helpful to measure estradiol in men being evaluated or treated for low testosterone?

There is now considerable evidence that estradiol levels in men play an important role in modulating the effects of testosterone on sexual function, body fat, lean muscle mass, and bone density. Nevertheless, estradiol levels are still not commonly measured in men who are being evaluated or treated for low-T. This is because the interpretive criteria for such testing are still not well understood. In some men, estradiol levels are measured in order to determine if TRT is causing an increase in estradiol due to aromatization of the testosterone. This can lead to symptoms of high estradiol such as bloating, fluid retention, and breast tenderness. Some experts now recommend calculating a ratio of testosterone to estradiol, but this approach is not yet widely accepted. Nevertheless, it is likely that clinical laboratories will experience an increased demand for estradiol testing in men as our understanding and prevalence of TRT increase.

Conclusion

From the preceding discussion, it should be apparent that our understanding of laboratory testing for low-T in men lags considerably behind the growing demand for testing and treatment of low-T. Clinical laboratories, manufacturers of in vitro diagnostic tests, and clinicians should be aware of the many unanswered questions in this field. They should also begin to prepare to educate themselves about the important changes in this field that are likely to occur in the next few years. For further details about this subject, the interested reader is referred to the following sources.

References

Bhasin S, Cunningham GR, Hayes FJ, Matsumoto AM, Snyder PJ, Swerdloff RS, Montori VM. Testosterone therapy in adult men with androgen deficiency syndromes: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006: 91, 1995-2010.

Finkelstein JS, et al. Gonadal steroids and body composition, strength and sexual function in men. N Engl J Med 2013: 369, 1011-22.

Morgentaler A, Khera M, Maggi M, Zitzmann M. Commentary: Who is a candidate for testosterone therapy? A synthesis of international expert opinions. J Sex Med 2014: 11, 2636-45.

www.peaktestosterone.com A testosterone and men’s health blog that is an excellent source of information and peer-reviewed publications on this topic.

The author

Michael Samoszuk, M.D.

Chief Medical Officer

Beckman Coulter Diagnostics