Diagnosis and other aspects of uromodulin kidney disease

Uromodulin kidney disease is a rare autosomal dominant kidney disease, characterized by hyperuricemia, gout and progressive kidney failure. Affected patients typically need renal replacement therapy in middle age. A considerable number of patients may reach end-stage kidney disease without a correct diagnosis, making improvements in diagnostic methods of vital importance.

by Dr Tamehito Onoe and Dr Mitsuhiro Kawano

Introduction

Uromodulin (UMOD), also known as Tamm–Horsfall protein, is the most abundant protein in healthy human urine. UMOD protein is a kidney-specific protein which is exclusively produced at the epithelial cells lining the thick ascending limb (TAL) of Henle’s loop.

The roles of urinary UMOD protein are assumed to be to protect against urinary tract infection, prevent urolithiasis formation and ensure water impermeability to create the countercurrent gradient. However, the accurate function and significance of UMOD protein are not yet fully elucidated [1].

Uromodulin kidney disease

Uromodulin kidney disease (UKD) is an inherited disease caused by UMOD gene mutations. So far, more than 100 mutations of the UMOD gene have been reported from all over the world [2]. Familial juvenile hyperuricemic nephropathy (FJHN), medullary cystic kidney disease type2 (MCKD2) and glomerulocystic kidney disease (GCKD), which are considered to be different diseases, have been proved to be caused by UMOD gene mutations [3]. Subsequently, because multiple names for one condition would be confusing and misleading, and also cysts are not pathognomonic for this disease, a new term, ‘Autosomal dominant tubulointerstitial kidney disease’ (ADTKD) was proposed in 2015 [4]. Mutations of renin (REN), hepatocyte nuclear factor 1β (HNF1β), and mucin-1 (MUC1) are also responsible for ADTKD besides UMOD. They all share common clinical characteristics, which are progressive kidney failure, tubulointerstitial nephritis and inheritance compatible with autosomal dominant trait with only trivial clinical differences. When UMOD mutation is identified in an ADTKD patient, the official diagnostic term is ADTKD-UMOD. However, UKD is also used to facilitate communication with patients, and so this term is used in the present article.

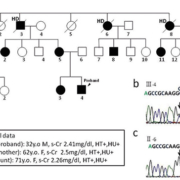

Patients with UKD have urinary concentration defect, hyperuricemia and gout from a young age. Their kidney function gradually deteriorates, and reaches end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) from 25 to 75 years of age. Their kidneys are usually of normal size or small and there are sometimes cysts, although the frequency of cysts does not differ from that of ‘non-cystic’ kidney diseases. Their urine tests usually show no or only very mild proteinuria or hematuria. The most prominent characteristic of UKD is a marked abundance of chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients in their pedigree, compatible with an autosomal dominant trait. Our group detected a novel A247P UMOD mutation in a UKD family (Fig. 1), many of whose members have hyperuricemia, CKD and ESKD, and are on hemodialysis (HD) therapy [5].

UKD is reported to be a rare disease, with a frequency of about 1.5 cases per million population. However, because hyperuricemia is a frequent complication in all CKD patients, when their family history is absent or unknown, it is difficult to suspect UKD, and so the frequency of UKD may be underestimated. This means that a certain proportion of UKD patients may reach ESKD without a correct diagnosis.

Diagnosis of uromodulin kidney disease

Clinically UKD should be suspected when a CKD patient has an abundant family history compatible with autosomal dominant trait, hyperuricemia, gout and bland urine findings. The final diagnosis of UKD is made by genetic test, which is, however, not commercially available, and only a limited number of laboratories are capable of performing it. So easier laboratory tests supportive of genetic tests would be helpful for the diagnosis of UKD and are awaited.

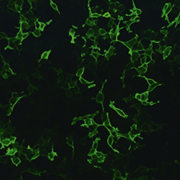

The renal histology of UKD patients shows nonspecific interstitial fibrosis, tubular atrophy and normal glomeruli. So it is difficult to make a diagnosis of UKD by ordinary histological methods. Moreover, not many UKD patients seem to undergo renal biopsy because their urine sediment shows no or only slight abnormalities and so clinicians may hesitate to undertake this invasive test. However, we believe that renal pathological examination is very informative not only for ruling out other kidney diseases but also for the diagnosis of UKD. UMOD proteins synthesized from mutated UMOD gene have protein folding disability and cannot escape from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) of the epithelial cells. Immunostaining using anti-UMOD antibody in kidney sections of UKD patients shows massive UMOD accumulation in their epithelial cells (Fig. 2). Because of the question of whether there are any UKD patients among those who received kidney biopsy and were diagnosed as having nephrosclerosis or interstitial nephritis, we performed the following investigation.

In a 3787-sample kidney biopsy database of Kanazawa University, patients meeting all of the following criteria were selected for UMOD immunostaining. (1) Renal insufficiency (serum creatinine >1.0 mg/dL) below 50 years of age; (2) hyperuricemia: serum uric acid higher than 7mg/dl or under treatment for hyperuricemia; (3) no or only very mild abnormalities in urinalysis; and (4) no other apparent renal disease present clinically or histopathologically. Finally, 15 patients were selected and abnormal UMOD accumulations were detected in three independent patients by UMOD immunostaining. A247P UMOD gene mutations were detected in the proband of the family in Figure 1 and the other independent patient, indicating that they may share the same ancestor. The other patient had no family history of CKD. These results show that there may be more UKD patients than expected before, and also indicate that when kidney biopsy shows only nonspecific interstitial fibrosis in patients with renal insufficiency, UMOD immunostaining may be considered to detect UKD with or without a family history of CKD, especially with hyperuricemia and bland urinary findings.

Most of the synthesized UMOD protein is carried to the apical membrane of epithelial cells and excreted in the urine. However, a low but considerable amount of UMOD protein goes to the basolateral membrane and is secreted into the serum [6]. Serum UMOD protein concentrations are reported to be 45–490 ng/mL, while urine UMOD protein concentrations are 1000–80 000 ng/mL. The functions and significance of serum UMOD proteins are unknown.

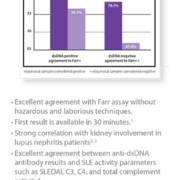

Some results of animal experiments indicate that UMOD protein has a renoprotective effect against various types of injury. A renal ischemia-reperfusion experiment in UMOD knockout mice showed significantly worse results than in wild-type animals [7]. It is well known that urinary UMOD concentrations in UKD patients are decreased. The authors recently reported that serum UMOD protein concentrations are also significantly decreased in UKD patients besides urinary UMOD (Fig. 3). Serum and urinary UMOD concentrations decline in parallel with the decrease of estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) due to the diminishment of UMOD producing epithelial cells in CKD patients. In UKD patients, the serum and urine UMOD concentrations were significantly lower compared with CKD patients beyond their eGFRs. Decreased serum and urinary UMOD concentrations may be good clues to suspect and diagnose UKD; however, verification in more UKD patients with various mutations will be indispensable.

Conclusions

So far no treatment has been devised that slows the rate of renal functional deterioration of UKD. At present, management for UKD patients is not different from that for other CKD patients. Anti-hyperuricemia drugs or anti-hypertensive therapy is used when necessary and the appropriate renal replacement therapy or renal transplantation should be considered when ESKD is reached. To clarify the pathogenesis and achieve effective treatment for UKD, establishment of more efficient diagnostic methods for UKD is expected. UMOD immunostaining for renal sections and measurement of serum and urinary UMOD concentrations are considered to be good modalities for the diagnosis of UKD. It is expected that through these tests, more UKD patients will be diagnosed at earlier stages and will be able to benefit from starting appropriate therapy before ESKD.

Recently some particular SNPs of UMOD promoter areas have been proved to be associated with hypertension or renal insufficiency from the genome-wide association study [8]. UMOD will likely attract greater attention as a renal-prognostic marker for not only UKD patients but also the general population.

References

1. Lhotta K, Piret SE, Kramar R, Thakker RV, Sunder-Plassmann G, Kotanko P. Epidemiology of uromodulin-associated kidney disease – results from a nation-wide survey. Nephron Extra 2012; 2: 147–158.

2. Scolari F, Izzi C, Ghiggeri GM. Uromodulin: from monogenic to multifactorial diseases. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2015; 30: 1250–1256.

3. Hart TC, Gorry MC, Hart PS, Woodard AS, Shihabi Z, Sandhu J, Shirts B, Xu L, Zhu H, Barmada MM, Bleyer AJ. Mutations of the UMOD gene are responsible for medullary cystic kidney disease 2 and familial juvenile hyperuricaemic nephropathy. J Med Genet. 2002; 39: 882–892.

4. Eckardt KU, Alper SL, Antignac C, Bleyer AJ, Chauveau D, Dahan K, Deltas C, Hosking A, Kmoch S, Rampoldi L, Wiesener M, Wolf MT, Devuyst O. Autosomal dominant tubulointerstitial kidney disease: diagnosis, classification, and management-A KDIGO consensus report. Kidney Int. 2015; 88(4): 676–683.

5. Onoe T, Yamada K, Mizushima I, Ito K, Kawakami T, Daimon S, Muramoto H, Konoshita T, Yamagishi M, Kawano M. Hints to the diagnosis of uromodulin kidney disease. Clin Kidney J. 2016; 9: 69–75.

6. Bachmann S, Koeppen-Hagemann I, Kriz W. Ultrastructural localization of Tamm-Horsfall glycoprotein (THP) in rat kidney as revealed by protein A-gold immunocytochemistry. Histochemistry 1985; 83: 531–538.

7. El-Achkar TM, Wu XR, Rauchman M, McCracken R, Kiefer S, Dagher PC. Tamm-Horsfall protein protects the kidney from ischemic injury by decreasing inflammation and altering TLR4 expression. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2008; 295: F534–544.

8. Trudu M, Janas S, Lanzani C, Debaix H, Schaeffer C, Ikehata M, Citterio L, Demaretz S, Trevisani F, Ristagno G, Glaudemans B, Laghmani K, Dell’Antonio G, Loffing J, Rastaldi MP, Manunta P, Devuyst O, Rampoldi L. Common noncoding UMOD gene variants induce salt-sensitive hypertension and kidney damage by increasing uromodulin expression. Nat Med. 2013; 19: 1655–1660.

The authors

Tamehito Onoe MD, PhD and Mitsuhiro Kawano* MD, PhD

Division of Rheumatology,

Department of Internal Medicine,

Kanazawa University Hospital,

Kanazawa, 920-8641,

Japan

*Corresponding author

E-mail: sk33166@gmail.com