RAS pathway biomarkers for breast cancer prognosis

Metastatic breast cancer is a highly heterogeneous, rapidly evolving and devastating disease that challenges our ability to find curative therapies. RAS pathway activation is an understudied research area in breast cancer. EGFR/RAS pathway activation is prevalent in breast cancer with poor prognosis. The prognostic RAS pathway biomarkers can be used to identify resistant tumour clones, stratify patients and guide therapies.

by L. L. Siewertsz van Reesema, M. P. Lee, Dr V. Zheleva, Dr J. S. Winston,

Dr C. F. O’Connor, Prof. R. R. Perry, Prof. R. A. Hoefer and Prof. A. H. Tang

Introduction

Breast cancer currently represents the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths among women in the United States [1]. In 2016 alone, an estimated 246 660 women will be diagnosed and an additional 40 450 women are expected to succumb to the disease process [1, 2]. By 2030, there are projected to be 294 000 new cases, making breast cancer a growing public health concern [3–5]. The increased breast cancer screenings, major technical advancements in breast cancer imaging and early detection, and targeted anti-cancer therapies have contributed to significant decreases in morbidity and mortality since the 1970s, and now more than 90% of patients with early-stage breast cancer have expected survival of much more than 5 years [2, 5]. Despite these amazing advancements, the prognosis for patients with high-grade, locally advanced and metastatic breast cancers remains poor with average survival less than 2 years [2, 6–8]. State-of-the-art treatments, such as anti-HER2 therapy, anti-ER therapy, anti-PI3K and anti-mTOR therapy, tumour genome-guided combination therapies, stem cell therapy, and anti-CTLA-4/PD1 immunotherapy, alone or in combination, are not curative in eradicating metastatic breast cancer [9–14]. The clinical reality is that despite similar clinical diagnoses and presentation, patients often display diverse tumour response to standard therapies. The intrinsic diversity and evolving heterogeneity of their mammary tumours can become more pronounced in relapsed or metastatic tumours after therapeutic intervention and clonal selection by ineffective treatment. This de novo and acquired tumour heterogeneity leads to diverse tumour responses in neoadjuvant and adjuvant setting following standard-of-care therapies, which in turn leads to varied clinical outcome and disparity in patient survival [6, 15, 16].

Currently, there are no reliable clinical biomarkers that can be used to consistently predict survival of patients with late-stage or metastatic breast cancers [6]. Classically utilized breast cancer biomarkers, such as estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) molecular subtypes, do not correlate with survival outcomes nor do they predict tumour responses to guided therapies in invasive disease [6]. Patients with malignant tumours are often subjected to full regimens of toxic therapies followed by a period of uncertainty awaiting to learn the response of their tumours and efficacy of their treatments. Unfortunately, some patients may be over-treated, which compromises their long-term quality of life, or, conversely, some patients may be under- or incorrectly treated and thus miss a critical window of opportunity to change prescribed anticancer regimens if therapy-resistant tumours persist after aggressive therapy. There is a pressing need to identify reliable, sensitive, and robust prognostic biomarkers to closely monitor tumour response in real-time, and, importantly, to determine whether first-line standard therapies prescribed are effective against high-risk and invasive mammary tumours, given diverse tumour response and intrinsic tumour heterogeneity [7, 16–21].

Current prognostic biomarkers used in breast cancer

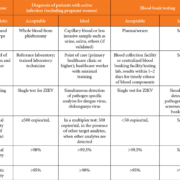

Clinicopathological parameters such as patient age, TMN (tumour size, lymph node status, metastasis) staging, tumour grade and histology, and molecular subtype of breast tumours have become commonplace in justifying medical decision making and prescribing treatment modalities. Therapies for invasive and high-risk breast cancer (luminal, basal-like, HER2-positive and triple-negative breast cancer) are routinely selected based on tumour ER, PR and HER2 status, in addition to aforementioned clinicopathological parameters [22–25]. The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) updated their clinical practice guidelines this year and according to the panel, only the current gold-standard biomarkers ER, PR, and HER2 should be used to guide treatment decisions, despite the fact they do not correlate with survival outcomes, nor predict tumour response to standard-of-care therapies [26].

ER-positive breast tumours account for the majority of cases worldwide [27]. Estrogen is the main stimulation for growth in the mammary tumours allowing this clinical biomarker to direct treatment planning and assess the benefit of mainstay anti-hormone therapies such as tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors. The expression of PR is frequently associated with ER-positive tumours where less than 1% of mammary tumours are PR-positive and ER negative [27]. Furthermore, PR expression has shown strong prognostic value with high level PR expression in invasive breast tumours displaying better outcomes to anti-hormone treatment when compared to low level PR expression [28]. Current guidelines put forth by the ASCO recommend ER and PR testing of all new cases of primary and distant recurrent breast tumours [29].

HER2 status has been identified as a strong indicator of patient overall survival. Overexpression of the HER2 oncogene leads to higher chances of relapse with shorter survival times. The development of anti-HER2 therapies, such as trastuzumab, in treating HER2 have been shown to have major benefit and therefore HER2 status is tested in the majority of breast cancer diagnoses [30]. Other emerging biomarkers such as Ki67 have a possible prognostic role in invasive breast cancers [31]. While the exact function is unknown, Ki67 is expressed in cycling tumour cells and it has strong correlation with tumour grade [31, 32]. Approaches to combining Ki67 with established biomarkers ER, PR, and HER2 are now being used to further distinguish breast cancers into clinical subtypes. However, the ASCO did not recommend using Ki67 to guide adjuvant therapies [29].

The ASCO has recognized the clinical utility of six multigene expression assays for specific subgroups of patients, including OncotypeDX (Genomic Health), EndoPredict (Sividon Diagnostics), PAM50 (Prosigna Breast Cancer Prognostic Gene Signature Assay), Breast Cancer Index, urokinase plasminogen activator, and plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 [33–37]. Most of these assays are recommended for patients with early-stage breast cancers only; none of these multi-gene assays were encouraged for patients with HER2-positive or triple-negative cancers, in addition to late-stage or metastatic cancers [34, 35]. The development of these promising gene signature-based molecular assessment tools for breast cancer is encouraging for the personalization of breast cancer therapies; however, there still remains an unmet medical need for patients with locally advanced and metastatic breast cancers.

The potential role of RAS pathway proteins in the prognosis and treatment of breast cancer

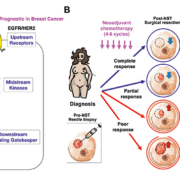

The oncogenic K-RAS carries the most common gain-of-function mutations in human cancer (30% of all human cancers) and its oncogenic role has been well-established in many types of human cancers [38, 39]. Thus, focusing on this tumour-promoting RAS signalling pathway is a logical choice of investigation for prognostic biomarker discovery and novel anticancer therapy development against oncogenic K-RAS-driven human cancer [40, 41]. The RAS pathway has been an intensely studied area of cancer research due to its activation of downstream effectors resulting in tumour proliferation, survival and motility (Fig. 1A). The loss of its most essential downstream signalling gatekeeper, SIAH (seven in absentia homologue), impeded oncogenic K-RAS-driven human pancreatic cancer and lung cancer [40, 42, 43]. Although oncogenic K-RAS mutations are rarely detected in mammary tumours (observed in about 5% of patients), genomic studies have indicated that the EGFR/HER2/K-RAS ‘pathway’ is activated in a large proportion of aggressive and malignant breast cancers [44, 45]. EGFR/HER2/K-RAS activation has been correlated with shortened survival, resistance to therapy, and tumour relapse despite aggressive treatments in breast cancer [44–47]. The mechanism and function of persistent RAS pathway activation remains elusive in breast cancer. This lack of mechanistic understanding, along with the low mutation rate of oncogenic RAS/RAF/MARK detected in mammary tumours, may contribute to the tumour-driving RAS pathway activation being understudied in the area of breast cancer research. It should also be noted that activation of RAS pathway in mammary tissues of animal models is adequate to induce oncogenic transformation and malignancy [48, 49]. Therefore, although there may not be any detectable RAS mutations in high-grade, locally advanced and metastatic breast tumours, alternative RAS pathway activation mechanisms of the RAS pathway downstream effectors may be present, promoting mammary tumorigenesis and metastasis.

Since RAS pathway activation is a major and essential signalling hub to promote human malignancies, we investigated whether EGFR/HER2/RAS pathway biomarker expression can be added to evaluate therapy efficacy and predict patient survival in breast cancer (Fig. 1A). It has been established that expression of SIAH, the most downstream signalling module and the most evolutionarily conserved component of the RAS signalling pathway, reflects RAS pathway activation, cell proliferation, and tumour growth [40, 42, 43]. In a retrospective study, 364 matched pairs of breast tumour specimens from 182 patients who received neoadjuvant systemic therapy (NST) were analysed to determine whether SIAH and/or EGFR outperform ER, PR, HER2, and Ki67 as a prognostic biomarker in locally advanced and metastatic breast cancer. The prognostic power of SIAH and EGFR, alone or in combination, is comparable to the clinical gold standards of clinical predictors (lymph node positivity, mammary tumour size, grade, stage and molecular subtypes in combination), and imaging-guided technology [50]. The activation/inactivation of the tumour-promoting RAS pathway biomarkers, SIAH and EGFR, is associated with tumour progression/regression in mammary tumours post-neoadjuvant systemic therapies (NST). We found that a marked reduction in SIAH/EGFR expression post-NST would indicate effective therapy and increased survival, while persistent high SIAH/EGFR expression post-NST would indicate ineffective therapy and decreased survival [50]. These results suggest that NST-induced reduction of SIAH and EGFR expression may be used as two useful surrogate prognostic biomarkers to quantify therapeutic efficacy, determine tumour responses, detect emerging resistant clones, and predict patient survival in high-grade and aggressive molecular subtype of breast cancer in the neoadjuvant setting in the future (Fig. 1B).

Conclusion

Early stage breast cancer is highly responsive to commonly prescribed standard of care therapies with excellent long-term survival. Locally advanced and metastatic breast cancer has a much worse prognosis despite aggressive chemo- and radiation therapies and locoregional surgical interventions. This disparity in prognosis underlines the acute need to tailor therapy and stratify patients in order to improve patient survival. The discovery of incorporating tumour heterogeneity-independent, therapy-responsive and tumour-driven RAS pathway biomarkers is prognostic in breast cancer, have a clear clinical impact to benefit breast cancer patients with locally advanced and metastatic diseases.

References

1. Siegel RL, et al. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016; 66: 7–30.

2. DeSantis C, et al. Breast cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014; 64: 52–62.

3. Anderson WF, et al. Incidence of breast cancer in the United States: current and future trends. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011; 103: 1397–1402.

4. Rahib L, et al. Projecting cancer incidence and deaths to 2030: the unexpected burden of thyroid, liver, and pancreas cancers in the United States. Cancer Res. 2014; 74: 2913–2921.

5. Graham LJ, et al. Current approaches and challenges in monitoring treatment responses in breast cancer. J Cancer 2014; 5: 58–68.

6. Tevaarwerk AJ, et al. Survival in patients with metastatic recurrent breast cancer after adjuvant chemotherapy: little evidence of improvement over the past 30 years. Cancer 2013; 119: 1140–1148.

7. Zardavas D, et al. Emerging targeted agents in metastatic breast cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2013; 10: 191–210.

8. Lobbezoo DJ, et al. Prognosis of metastatic breast cancer subtypes: the hormone receptor/HER2-positive subtype is associated with the most favorable outcome. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013; 141: 507–514.

9. El Saghir NS, et al. Treatment of metastatic breast cancer: state-of-the-art, subtypes and perspectives. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2011; 80: 433–449.

10. Engelman JA. Targeting PI3K signalling in cancer: opportunities, challenges and limitations. Nat Rev Cancer 2009; 9: 550–562.

11. McKeage K, Perry CM. Trastuzumab: a review of its use in the treatment of metastatic breast cancer overexpressing HER2. Drugs 2002; 62: 209–243.

12. Piccart-Gebhart MJ, et al. Trastuzumab after adjuvant chemotherapy in HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005; 353: 1659–1672.

13. Robert N, et al. Randomized phase III study of trastuzumab, paclitaxel, and carboplatin compared with trastuzumab and paclitaxel in women with HER-2-overexpressing metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006; 24: 2786–2792.

14. Romond EH, et al. Trastuzumab plus adjuvant chemotherapy for operable HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005; 353: 1673–1684.

15. Vogelstein B, et al. Cancer genome landscapes. Science 2013; 339: 1546–1558.

16. Zardavas D, et al. Clinical management of breast cancer heterogeneity. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2015; 12: 381–394.

17. Coley HM. Mechanisms and strategies to overcome chemotherapy resistance in metastatic breast cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2008; 34: 378–390.

18. Haddad TC, Goetz MP. Landscape of neoadjuvant therapy for breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015; 22: 1408–1415.

19. Holohan C, et al. Cancer drug resistance: an evolving paradigm. Nat Rev Cancer 2013; 13: 714–726.

20. Hutchinson L. Breast cancer: challenges, controversies, breakthroughs. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2010; 7: 669–670.

21. King TA, Morrow M. Surgical issues in patients with breast cancer receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2015; 12: 335–343.

22. Baselga J, et al. Pertuzumab plus trastuzumab plus docetaxel for metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012; 366: 109–119.

23. Bevers TB, et al. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: breast cancer screening and diagnosis. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2009; 7: 1060–1096.

24. Redden MH, Fuhrman GM. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy in the treatment of breast cancer. Surg Clin North Am. 2013; 93: 493–499.

25. Tolaney SM, et al. Adjuvant paclitaxel and trastuzumab for node-negative, HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015; 372: 134–141.

26. Hammond ME, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology/College Of American Pathologists guideline recommendations for immunohistochemical testing of estrogen and progesterone receptors in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010; 28: 2784–2795.

27. Viale G, et al. Prognostic and predictive value of centrally reviewed expression of estrogen and progesterone receptors in a randomized trial comparing letrozole and tamoxifen adjuvant therapy for postmenopausal early breast cancer: BIG 1–98. J Clin Oncol. 2007; 25: 3846–3852.

28. Dowsett M, et al. Benefit from adjuvant tamoxifen therapy in primary breast cancer patients according oestrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, EGF receptor and HER2 status. Ann Oncol. 2006; 17: 818–826.

29. Runowicz CD, et al. American Cancer Society/American Society of Clinical Oncology Breast Cancer Survivorship Care Guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2016; 34: 611–635.

30. Weigel MT, Dowsett M. Current and emerging biomarkers in breast cancer: prognosis and prediction. Endocr Relat Cancer 2010; 17: R245–262.

31. Falato C, et al. Ki67 measured in metastatic tissue and prognosis in patients with advanced breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014; 147: 407–414.

32. Bulfoni M, et al. In patients with metastatic breast cancer the identification of circulating tumor cells in epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition is associated with a poor prognosis. Breast Cancer Res. 2016; 18: 30.

33. Sparano JA, et al. Prospective validation of a 21-gene expression assay in breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;.

34. Gyorffy B, et al. Multigene prognostic tests in breast cancer: past, present, future. Breast Cancer Res. 2015; 17: 11.

35. Goncalves R, Bose R. Using multigene tests to select treatment for early-stage breast cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013; 11: 174–182; quiz 182.

36. van ‘t Veer LJ, et al. Gene expression profiling predicts clinical outcome of breast cancer. Nature 2002; 415: 530–536.

37. Oakman C, et al. Breast cancer assessment tools and optimizing adjuvant therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2010; 7: 725–732.

38. Downward J. Targeting RAS signalling pathways in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003; 3: 11–22.

39. Pylayeva-Gupta Y, et al. RAS oncogenes: weaving a tumorigenic web. Nat Rev Cancer 2011; 11: 761–774.

40. Van Sciver RE, et al. Blocking SIAH proteolysis, an important K-RAS vulnerability, to control and eradicate K-RAS-driven metastatic cancer. In: A. Azmi (Ed.) Conquering RAS, Elsevier, 2016.

41. McCormick F. KRAS as a therapeutic target. Clin Cancer Res. 2015; 21: 1797–1801.

42. Ahmed AU, et al. Effect of disrupting seven-in-absentia homolog 2 function on lung cancer cell growth. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008; 100: 1606–1629.

43. Schmidt RL, et al. Inhibition of RAS-mediated transformation and tumorigenesis by targeting the downstream E3 ubiquitin ligase seven in absentia homologue. Cancer Res. 2007; 67: 11798–11810.

44. Arteaga CL, et al. Treatment of HER2-positive breast cancer: current status and future perspectives. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2012; 9: 16–32.

45. Foulkes WD, et al. Triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010; 363: 1938–1948.

46. Tebbutt N, et al. Targeting the ERBB family in cancer: couples therapy. Nat Rev Cancer 2013; 13: 663–673.

47. Wright KL, et al. Ras signaling is a key determinant for metastatic dissemination and poor survival of luminal breast cancer patients. Cancer Res. 2015; 75: 4960–4972.

48. Creedon H, et al. Use of a genetically engineered mouse model as a preclinical tool for HER2 breast cancer. Dis Model Mech. 2016; 9: 131–140.

49. Politi K, Pao W. How genetically engineered mouse tumor models provide insights into human cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2011; 29: 2273–2281.

50. van Reesema LL, et al. SIAH and EGFR, two RAS pathway biomarkers, are highly prognostic in locally advanced and metastatic breast cancer. EBioMedicine 2016; 11: 183–198.

The authors

Lauren L. Siewertsz van Reesema†*1 BS; Michael P. Lee†1 MS; Vasilena Zheleva2 MD; Janet S. Winston3 MD; Caroline F. O’Connor4 MD; Roger R. Perry2 MD, FACS; Richard A. Hoefer5,6,7 DO, FACS; Amy H. Tang*4,8 PhD

1Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, VA 23507, USA

2Department of Surgery, Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, VA 23507, USA

3Sentara Pathology and Pathology Sciences Medical Group, Sentara Norfolk General Hospital (SNGH), Norfolk, VA 23507, USA

4Department of Microbiology and Molecular Cell Biology, Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, VA 23507, USA

5Sentara Cancer Network, 6Dorothy G. Hoefer Comprehensive Breast Center, 7Sentara CarePlex Hospital, Newport News, Virginia 23606, USA

8Leroy T. Canoles Jr. Cancer Research Center, Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, VA 23507, USA

†Authors contributed equally to this publication.

*Corresponding author

E-mail: Tangah@evms.edu