Improving diagnosis of Zika virus infection: an urgent task for pregnant women

Zika virus (ZIKV) belongs to the Flavivirus genus and is related to other viruses that are also transmitted by the bite of mosquitoes, such as dengue virus (DENV), yellow fever virus (YFV) and West Nile virus (WNV). The Flaviviridae family comprises single-strand RNA, membrane-enveloped viruses that frequently use Aedes aegypti as a vector. Despite ZIKV being discovered over 60 years ago, only since 2014 (in the French Polynesia Islands) and 2015 (Brazil and America) has it been evident that the virus can cause large outbreaks and epidemics that lead to a global public health emergency [1].

ZIKV infection causes a mild severity, undifferentiated febrile syndrome, characterized by rash, arthralgia, myalgia and conjunctivitis, symptoms that are similar to those that appear in DENV fever or chikungunya virus (CHIKV) fever (CHIKV being an unrelated alphavirus transmitted by the same mosquito). The similarities of the symptoms causes confusion between the diseases during clinical evaluation. Also, these three viral illnesses may co-circulate in the same areas, hampering the final diagnosis of patients.

Although the ZIKV morbidity and mortality are considered low, it was demonstrated during the recent outbreaks that infection in pregnant women may be associated with severe birth defects (mostly microcephaly), and with the appearance in infected adults of a severe neurologic disease called Guillain–Barré syndrome (GBS). This neurologic entity increased 2–10-fold the historic cases in Latin America during the 2016 ZIKV epidemic [2]. Epidemiological estimates consider that approximately 75% of ZIKV-infected people do not present signs or symptoms during an outbreak, but they become an efficient transmission focus to mosquitoes and other individuals.

It is well known that mosquito bites are the main transmission route in areas where the insect infestation rates are high; however, it recently has been confirmed that ZIKV is capable of crossing the placental barrier and infecting the fetus. In adult patients, the virus persists in semen and vaginal fluids for two months, producing a viral load sufficient for transmission during sexual intercourse. This finding changes the epidemiological trends, as it is now also possible to detect infected patients in non-tropical countries, challenging the clinical and laboratory diagnosis. However, it is clear that tropical underdeveloped countries will still be the major source of febrile cases and, of course, the congenital malformations and GBS appearance in adults.

ZIKV infection diagnostics

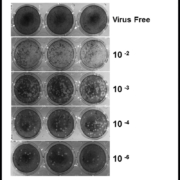

The incubation period of ZIKV disease is not clear but is likely to be a few days, similar to other arboviruses. Symptoms can begin 2 to 7 days after a mosquito bite and last for 3 to 7 additional days. In both early symptomatic or asymptomatic cases, the virus can be detected by reverse transcription (RT)-PCR after purification of plasma or serum RNA. The acute sera can be inoculated in Vero cells or C6/36 mosquito cells to attempt virus isolation, but although this technique is powerful, it is expensive and lacks clinical value. We successfully isolated ZIKV and produced enough inoculum for cell biology and immunologic studies (Fig. 1). As a result of their sensitivity and specificity, ZIKV RNA detection by different nucleic acid tests is used on a routine basis to confirm acute ZIKV cases.

RT-PCR

The real-time RT-PCR protocol designed by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC, USA) during the 2007 Yap Island outbreak is the most used and evaluated, even after the confirmation that a very low viral load occurs during the acute phase and that viremia lasts only a few days in both symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals. This CDC protocol does not amplify RNA from other flaviviruses and alphaviruses [3].

The test was designed as a one-step RT-PCR with fluorogenic probes using serum as the sample and is also used on urine samples, where the virus can be detected until 15 days after symptoms start and when the serum sample has become negative. A comparison between different sample types demonstrated that saliva may be better than serum for confirming ZIKV infection [4]. A very sensitive and specific synthetic biology tool based on isothermal amplification and toehold switch RNA sensors has been reported and is currently under evaluation in field conditions in Colombia, Brazil and Equator [5].

Many other real-time PCR tests have recently been developed, but there are no reports regarding their clinical evaluation. One test with excellent analytical performance is becoming available (Altona Diagnostics), but it has not yet reported clinical assays in ZIKV circulating zones.

Frequently, conventional PCR has been used to follow epidemics and ZIKV circulation in mosquitoes [6], and this reported test was used to confirm the first cases in Brazil. Recently, we used modified primers to perform a double-round one-step RT-PCR to detect DENV, ZIKV and CHIKV in the serum of febrile patients, obtaining samples simultaneously positive for two or even three viruses [7]. This test also detects ZIKV RNA in paired samples of serum, breast milk and urine (Fig. 2).

Serology

The main challenge to serological ZIKV diagnosis is related to its structural proximity to other flaviviruses (DENV, YFV, and WNV) because antibodies against one of them can recognize the other viruses on ELISA platforms, frequently resulting in a false positive diagnostic. For this reason, RNA detection is preferred to confirm the infection during the first week after symptoms appear. However, serological tests are recommended to facilitate the diagnosis of pregnant women living in endemic zones or women or couples wanting pre-conception counselling because ZIKV IgM positivity confirms previous exposure to the virus; in those who are negative, it is recommended to perform periodic tests to prove the absence of virus contact.

Since the first serological diagnostics were performed in Africa, there have been difficulties confirming the infection by antibodies due to cross-reactivity in neutralization tests, hemagglutination inhibition and mouse neutralization used in the 1950s [8]. During the Yap Islands’ 2007 ZIKV outbreak, in addition to molecular confirmation, 14 ZIKV cases were investigated by serology, and it was confirmed that 8/14 individuals who had a previous flavivirus infection (secondary flavivirosis) were positive by DENV IgM ELISA. In addition, ZIKV-confirmed sera had high titres in the plaque reduction neutralization test (PRNT), mainly to DENV (12/14), YFV (3/14) and WNV (6/14) [3].

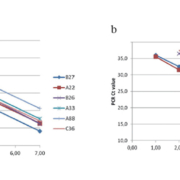

Currently, the CDC uses IgM antibody capture (MAC)-ELISA in its diagnostic algorithm, in which the ZIKV antigen is obtained from infected mice brains or recombinant proteins (Fig. 3a). This test is being used to confirm recent infections and to counsel women in endemic zones. This ELISA has not yet been tested in endemic zones where other flaviviruses circulate. Recently, an assay based on non-structural protein NS1 from ZIKV adsorbed to ELISA plates has been reported (Euroimmun AG), showing excellent performance to detect both IgM and IgG using samples from endemic zones and samples with confirmed contact with other flaviviruses (Fig. 3b) [9].

Pregnant women: the priority

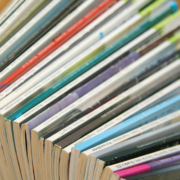

Considering that ZIKV infection during the first two trimesters of pregnancy can be associated with neurological defects in the fetus, it is important to evaluate the infection risk in three different groups of women: (i) women of childbearing age living in areas with virus circulation; (ii) women travelling frequently to endemic zones; and (iii) women having sexual intercourse with individuals travelling frequently to ZIKV endemic zones (Table 1). Notably, only 25% of infected individuals present signs or symptoms of the disease, but those who are asymptomatic can transmit the virus to mosquitoes and through sexual contact, can develop GBS or can transmit the virus to the fetus during pregnancy. Normally, health authorities do not recommend confirming all cases by PCR or serology, but only those needed to facilitate the surveillance of ZIKV infections or sequelae (Table 1).

CDC testing algorithm

In zones with ZIKV circulation, pregnant women should be assessed for ZIKV exposure (with or without signs or symptoms). If there are fewer than 2 weeks of putative exposition, the recommended test is RT-PCR in both serum and urine samples. If these results are negative, an IgM ZIKV-ELISA should be performed 2–12 weeks later. If the pregnant woman visits the healthcare system 2–12 weeks after having symptoms or the putative exposure, the recommended test is ZIKV IgM ELISA with simultaneous testing of IgM to DENV. If both are positive, it means a recent flavivirus infection. In this case, it is necessary to evaluate antibody titres to each virus using a plaque reduction neutralization assay (PRNT). If the neutralization titres to ZIKV are >10, the diagnosis is a recent ZIKV infection [10].

In both confirmed and presumptive ZIKV infection during pregnancy, serial ultrasounds should be performed every 3–4 weeks to assess fetal anatomy and growth. Amniocentesis to evaluate fetal infection is not recommended. After birth, neonatal serum and urine should be tested by RT-PCR and IgM. If CSF is obtained for other reasons, it can also be tested. The placenta and umbilical cord, as well as tissues from fetal losses, can be processed for PCR and immunohistochemistry.

Conclusion

Emergent ZIKV is here to stay. Virus transmission can occur during the entire year because of the tropical weather and generalized A. aegypti infestation in developing countries. Because of the concurrent arbovirus epidemics and the overlapping endemic regions, the differential diagnosis must always include ZIKV, DENV and CHIKV. The development of new technical approaches to diagnose ZIKV infections and the clinical trials to evaluate them is an imperative need, mainly because of the deep impact on childbearing women in endemic zones.

References

1. Abushouka AI, Negidac A, Ahmed H. An updated review of Zika virus. J Clin Virol 2016; 84: 53–58.

2. Dos Santos T, Rodriguez A, Almiron M, Sanhueza A, Ramon P, et al. Zika virus and the Guillain–Barré syndrome – case series from seven countries. N Engl J Med 2016; 375(16): 1598–1601.

3. Lanciotti RS, Kosoy OL, Laven JJ, Velez JO, Lambert AJ, et al. Genetic and serologic properties of Zika virus associated with an epidemic, Yap State, Micronesia, 2007. Emerg Infect Dis 2008; 14(8): 1232–1239.

4. Musso D, Roche C, Nhan TX, Robin E, Teissier A, Cao-Lormeau VM.Detection of Zika virus in saliva. J Clin Virol 2015; 68: 53–55.

5. Pardee K, Green AA, Takahashi MK, Braff D, Lamber G, et al. Rapid, Low-Cost Detection of Zika Virus Using Programmable Biomolecular Components. Cell 2016; 165: 1255–1266.

6. Faye O, Faye O, Dupressoir A, Weidmann M, Ndiaye M, Alpha Sall A. One-step RT-PCR for detection of Zika virus. J Clin Virol 2008; 43(1): 96–101.

7. Calvo EP, Sánchez-Quete F, Durán S, Sandoval I, Castellanos JE. Easy and inexpensive molecular detection of dengue, chikungunya and zika viruses in febrile patients. Acta Tropica 2016; 163: 32–37.

8. Musso D, Lanteri MC. Thoughts around the Zika virus crisis. Curr Infect Dis Rep 2016; 18(12): 46.

9. Steinhagen K, Probst C, Radzimski C, Schmidt-Chanasit J, Emmerich P, et al. Serodiagnosis of Zika virus (ZIKV) infections by a novel NS1-based ELISA devoid of cross-reactivity with dengue virus antibodies: a multicohort study of assay performance, 2015 to 2016. Euro Surveill 2016; 21(50): pii: 30426.

10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim pregnancy guidance: testing and interpretation recommendations for a pregnant woman with possible exposure to Zika virus — United States (including U.S. territories). [https://www.cdc.gov/zika/pdfs/testing_algorithm.pdf]

The authors

Jaime E. Castellanos PhD, Shirly Parra-Álvarez and Eliana P. Calvo* PhD

Grupo de Virología, Universidad El Bosque, Bogotá, Colombia

*Corresponding author

E-mail: calvoeliana@unbosque.edu.co