Metabolic syndrome is characterized by a collection of disorders, making it difficult to diagnose and stage. This article describes the criteria used for diagnosis as well as discussing treatment strategies.

by Prof. Giuseppe Derosa and Dr Pamela Maffioli

Definition and grading

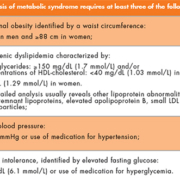

Metabolic syndrome is a combination of medical disorders that increases the risk of developing cardiovascular disease; it affects one in five people in the United States, and prevalence increases with age. There are different definitions of metabolic syndrome; according to the Adult Treatment Panel (ATP) III [1], metabolic syndrome requires the presence of at least three of the listed criteria (Table 1).

Recently insulin resistance has been cited to be associated with other metabolic risk factors and correlates with cardiovascular risk. The pro-inflammatory state has also been developed and used as a marker to predict coronary vascular diseases in metabolic syndrome: it is identified by higher C-reactive protein (CRP) levels, commonly present in people with metabolic syndrome. One cause of elevated CRP is obesity, because adipose tissue releases inflammatory cytokines that may elicit higher CRP levels. Also, the pro-thrombotic state has been recently considered for the definition of metabolic syndrome, characterized by increased plasma plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) and fibrinogen. However, the ATP III panel did not find adequate evidence to recommend routine measurement of insulin-resistance, pro-inflammatory state (e.g. high-sensitivity C-reactive protein), or pro-thrombotic state (e.g. fibrinogen or PAI-1) in the diagnosis of the metabolic syndrome.

The World Health Organization (WHO) criteria, instead, emphasized insulin resistance as the major underlying risk factor and required evidence of insulin resistance for diagnosis (Table 2) [2, 3].

The International Diabetes Federation (IDF), instead, dropped the WHO requirement for insulin resistance, but made abdominal obesity necessary for the diagnosis, with particular emphasis on waist measurement as a simple screening tool [4]; the other criteria (Table 3) were essentially identical to those provided by ATP III [1].

The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) proposed a third set of clinical criteria for the insulin resistance syndrome [5]. These criteria appear to be a hybrid of those of the ATP III and WHO metabolic syndrome. However, no defined number of risk factors is specified and diagnosis is left to clinical judgment (Table 4).

Given that multiple definitions of the same disease can generate confusion among physicians, the major organizations made an attempt to unify the various criteria for the definition of metabolic syndrome [6]. It was agreed that there should not be an obligatory component, but that waist measurement would continue to be a useful preliminary screening tool. Three abnormal findings out of five would qualify a person for the metabolic syndrome according to the unified definition shown in Table 5.

As readers can easily understand, individuals with metabolic syndrome are at increased risk for coronary heart disease (CHD) [7]. In particular, in the absence of diabetes, the metabolic syndrome generally did not raise the 10-year risk for CHD by more than 20% [8], in particular 10-year risk generally ranged from 10% to 20% for men and did not exceed 10% for women. However, in the presence of diabetes, the risk increases. Obviously, patients fulfilling all or almost all of the metabolic syndrome potential criteria, have earlier and more serious organ damage, at both cardiac and vascular levels, than patients with only three out of five components of the metabolic syndrome definition.

Treatment

Despite the grade of metabolic syndrome, however, there are two general approaches to its treatment. The first strategy modifies root causes, overweight/obesity and physical inactivity, and their closely associated condition, insulin resistance. The second approach directly treats the metabolic risk factors such as atherogenic dyslipidemia, hypertension, the pro-thrombotic state, and underlying insulin resistance. ATP III recommended that obesity be the primary target of intervention for metabolic syndrome [9]. First-line therapy should be weight reduction; the current recommendations for the treatment of overweight and obese people include increased physical activity and reduced calorie intake [10, 11]. Pharmacological treatment with orlistat can be another option, and when it is not tolerated, bariatric surgery should be considered. However, surgery irreversibly changes the overall architecture of the digestive tract; in this regard, the endoscopic duodenal–jejunal bypass liner can be another option. It consists of a sheath that is inserted endoscopically through the mouth into the digestive tract of the obese patient creating a physical barrier between the intestinal wall and the food ingested. The device can be considered as an alternative to bariatric surgery because of the minimal adverse events and the possibility to easily remove the device when the desired weight has been achieved [12]. Weight loss is important because it lowers serum cholesterol and triglycerides, raises HDL-cholesterol, lowers blood pressure and glucose, and reduces insulin resistance. Published data further show that weight reduction can decrease serum levels of CRP and PAI-1 [13–16]. In addition, other lipid and non-lipid risk factors associated with the metabolic syndrome should be appropriately treated. Atherogenic dyslipidemia includes elevated serum triglycerides and apolipoprotein B, increased small LDL particles, and reduced level of HDL-cholesterol. The treatment strategy for atherogenic dyslipidemia in metabolic syndrome focuses on triglycerides. If triglycerides are ≥150 mg/dL and HDL-cholesterol is <40 mg/dL, a diagnosis of atherogenic dyslipidemia is made. If triglycerides are <200 mg/dL, and specific drug therapy to reduce triglyceride-rich lipoproteins is not indicated. However, if the patient has CHD or CHD risk equivalents, LDL-cholesterol goal has to be considered together with the use of a drug to raise HDL-cholesterol (fibrate). On the other hand, if triglycerides are 200–499 mg/dL, non-HDL cholesterol becomes a secondary target of therapy. Goals for non-HDL cholesterol are 30 mg/dL higher than those for LDL-cholesterol. First the LDL-cholesterol goal is attained, and if non-HDL remains elevated, additional therapy may be required to achieve the non-HDL goal. Alternative approaches for treatment of elevated non-HDL cholesterol that persists after the LDL goal has been achieved are (a) higher doses of statins, or (b) moderate doses of statins + triglyceride-lowering drug (fibrate). If triglycerides are very high (≥500 mg/dL), attention turns first to prevention of acute pancreatitis, which is more likely to occur when triglycerides are >1000 mg/dL. Triglyceride-lowering drugs (fibrate) become the first line therapy; although statins can be used to lower LDL-cholesterol to reach the LDL-cholesterol goal, in these patients it is often difficult (and unnecessary) to achieve a non-HDL cholesterol goal of only 30 mg/dL higher than for LDL-cholesterol [9].

Conclusion

In conclusion, metabolic syndrome increases cardiovascular risk; a multifactorial approach is necessary in order to prevent the development of the various components of this disease.

References

1. National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). Third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation 2002; 106: 3143–3421.

2. Alberti KG, Zimmet PZ. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus: provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabet Med. 1998; 15: 539–553.

3. World Health Organization. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications: report of a WHO Consultation. Part 1: diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1999. Available at: http:// whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/1999/WHO_NCD_NCS_99.2.pdf.

4. Alberti KG, Zimmet P, Shaw J; IDF Epidemiology Task Force Consensus Group. The metabolic syndrome: a new worldwide definition. Lancet 2005; 366: 1059–1062.

5. Einhorn D, Reaven GM, Cobin RH, Ford E, Ganda OP, Handelsman Y, Hellman R, Jellinger PS, Kendall D, Krauss RM, Neufeld ND, Petak SM, Rodbard HW, Seibel JA, Smith DA, Wilson PW. American College of Endocrinology position statement on the insulin resistance syndrome. Endocr Pract. 2003; 9: 237–252.

6. Alberti KG, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ, Cleeman JI, Donato KA, Fruchart JC, James WP, Loria CM, Smith SC Jr; International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; Hational Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; International Association for the Study of Obesity. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation 2009; 120 (16): 1640–1645.

7. Lakka HM, Laaksonen DE, Lakka TA, et al. The metabolic syndrome and total and cardiovascular disease mortality in middle-aged men. JAMA 2002; 288: 2709–2716.

8. Wilson PW, D’Agostino RB, Levy D, Belanger AM, Silbrshatz H, Kannel WB. Prediction of coronary heart disease using risk factor categories. Circulation 1998; 97: 1837–1847.

9. National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation. 2002; 106 (25): 3143–3421.

10. American Diabetes Association. Nutrition principles and recommendations in diabetes. Diabetes Care 2004; 27(S1): 36–46.

11. American Diabetes Association. Physical activity/exercise and diabetes. Diabetes Care 2004; 27(S1): 58–62.

12. Derosa G, Maffioli P. Possible therapies for obesity: focus on the available options for its treatment. Nutrition 2014; doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2014.09.005.

13. Dengel DR, Galecki AT, Hagberg JM, Pratley RE. The independent and combined effects of weight loss and aerobic exercise on blood pressure and oral glucose tolerance in older men. Am J Hypertens. 1998; 11: 1405–1412.

14. Ahmad F, Considine RV, Bauer TL, Ohannesian JP, Marco CC, Goldstein BJ. Improved sensitivity to insulin in obese subjects following weight loss is accompanied by reduced protein-tyrosine phosphatases in adipose tissue. Metabolism 1997; 46: 1140–1145.

15. Su HY, Sheu WH, Chin HM, Jeng CY, Chen YD, Reaven GM. Effect of weight loss on blood pressure and insulin resistance in normotensive and hypertensive obese individuals. Am J Hypertens. 1995; 8: 1067–1071.

16. Derosa G, Limas CP, Macías PC, Estrella A, Maffioli P. Dietary and nutraceutical approach to type 2 diabetes. Arch Med Sci. 2014; 10(2): 336–344.

The authors

Giuseppe Derosa1,2 MD, PhD, Pamela Maffioli1,3 MD

1Department of Internal Medicine and Therapeutics, University of Pavia, Fondazione IRCCS Policlinico S. Matteo, PAVIA, Italy.

2Center for the Study of Endocrine-Metabolic Pathophysiology and Clinical Research, University of Pavia, PAVIA, Italy.

3PhD School in Experimental Medicine, University of Pavia, PAVIA, Italy

E-mail: giuseppe.derosa@unipv.it