Laboratory assessment of mild traumatic brain injury by use of neurotoxicity biomarkers

Mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) and concussion from sporting/recreational activities are relatively common. However, assessment of mTBI is difficult and many incidents of mTBI and concussion are unrecognized and/or not reported. Levels of the α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptor (AMPAR) peptide, a product of the proteolytic degradation of AMPA receptors, have been found to be raised in mTBI and the development of point-of-care (POC) tests based on the recognition of the AMPAR peptide is underway. Such POC tests will be useful at the pitch sideline or in the combat field for aiding objective diagnosis and management of subtle brain injury.

by Prof. Svetlana A. Dambinova, Rozalyn Heath and Dr Galina A. Izykenova

Introduction

Mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) including concussion is the most frequent form of injury in military and civilian settings with the highest prevalence among young adults aged 15 to 24 years. Each year sports and recreational activities contribute about 3.8 million cases of mTBI in the USA [1], whereas brain injuries caused by explosions are the most common combat wounds in the military arena.

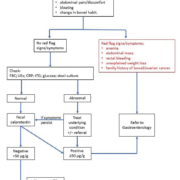

Assessment of mTBI regardless of origin is complicated. Many primary mTBIs, and particularly concussions, go unrecognized or are not reported when there is no loss of consciousness. Additionally, without sufficient reports of previous incidents, soldiers and competitive athletes are often subjected to multiple concussions. There are several challenges to identify immediate (or primary acute and subacute within 24 hours and up to 2 weeks respectively) impact, secondary (beyond 14 days) and cumulative (brain-related seizures) consequences that might follow multiple concussions or mTBI.

Normally, acute subclinical concussions associated with micro-edema formation that is reversible and not visible on conventional computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) methods. Advanced neuroimaging techniques (diffusion tensor imaging, functional MRI, and positron emission tomography) that can register minor structural and microvascular changes are primarily used for research. These modalities are not available in emergency situations or for routine clinical evaluations and have a limited application in persons with metal implants [2] or claustrophobia [3].

Currently, there is an unmet diagnostic need to reveal brain micro-damage following concussion by use of a rapid and affordable assay detecting, for instance, neurotoxicity (immunoexcitotoxicity) biomarkers in the bloodstream [4]. Analogous to NR2 peptide as a biomarker for cortical lesions in transient ischemic attack (TIA)/strokes [5], we proposed that the α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptor (AMPAR) peptide marker is able to differentiate subtle brain injury in white matter associated with concussions.

Neurotoxicity biomarkers in mTBI

It is known that the family of ionotropic glutamate receptors (GluRs) implying N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDAR), AMPAR and kainite receptors are involved in the regulation of synaptic connectivity in cortical/subcortical and brainstem areas [4,5]. Recently, it was shown that AMPAR represents a biomarker for the neurotoxicity cascade underlying subtle brain injury [6].

The family of location-specific GluRs is involved in more than 80% of cortical and subcortical neuronal communications underlying superior mental functions [7]. AMPAR is primarily distributed in the forebrain and subcortical pathways [8], and strategically located on surfaces of small cerebral arteries regulating blood circulations in white matter substructures [9]. Symptomatically the impact to brain may lead to executive brain dysfunctions associated with subcortical areas. Visual and cognitive deficits (including problems with memory, intellect, concentration and attention) might be an aftermath of subtle repetitive injuries to deep brain structures due to more severe cases of mTBI.

In acute and subacute phases of mTBI, a massive release of glutamate, which upregulates excitotoxic AMPARs has been detected [4]. The GluR1-subunit of N-terminal AMPAR fragments is rapidly cleaved by extracellular proteases and fragments carrying immune active epitopes released into the bloodstream through the compromised blood–brain barrier (BBB). This degradation product can be detected directly in the blood as AMPAR peptide fragments (molecular weight 5–7 kDa) [4]. The protective effects of a compromised BBB impacting neurotoxicity are exacerbated further when accompanied by a delayed immunological response generating peripheral anti-CNS antibodies [10].

Concussion assays development

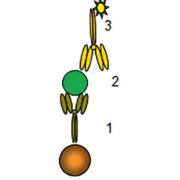

To detect AMPAR peptide, magnetic-particle-based enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (MP-ELISA) containing unique reagents has been developed. MP-ELISA involved a sandwich or ‘bridging’ assay where the suspended in solution microparticles coated by capture antibodies are binding to two epitopes of AMPAR peptide and reaction is revealed by probe-detection antibodies (Fig. 1). The probe is an enzyme that generates a colour reaction. The assay includes control samples (reference standards) produced synthetically or as a fusion human protein.

A feasibility study detecting the AMPAR peptide in a single blood draw taken from club sport athletes and professional football players in acute and subacute stage of concussions evaluated cut-offs of 0.4 and 1.0 ng/mL respectively for the assessment of single and recurrent concussions (Table 1) [11,12]. The predictive value of the test was assessed as 91% with a likelihood ratio of 11–12 for recognizing individuals with mTBI. If the test at a cut-off point of 0.4 ng/mL was negative, the post-test probability for a single concussion would be <4%.

AMPAR peptide concentrations in plasma for a military cohort suffering mTBI showed increased levels with an average concentration of 2.98 ng/mL [13]. In this study, the optimal cut-off value for recurrent mTBI was similar to professional players (Table 1), at which a positive predictive value of 93% was achieved. The trade-offs between true-positive and false-positive yielded in an area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of 0.97.

Early experimental and clinical research of antibodies to AMPA receptors (AMPAR Ab) as an immunoexcitotoxicity biomarker has demonstrated their diagnostic value in detecting pathological brain-spiking activity and epileptic seizures [14,15] as a consequence of traumatic brain injury, thereby representing a prognostic risk factor [16]. Clinical studies of GluR1 antibodies in adult patients with different chronic neurological pathology (n=1866) performed in Russia, Germany, Ireland, Poland and the USA have demonstrated diagnostic potential (sensitivity of 86%-88% and specificity of 83–97%) in assessment of post-traumatic seizures.

In sport-related multiple concussions, AMPAR Ab values remained abnormally high in the blood of some athletes who had headaches and visual problems. It was suggested that this finding may reflect persistent changes in the subcortical areas of the brain. The diagnostic value of AMPAR Ab (sensitivity of 86–88%, specificity of 83–97% at 1.5 ng/ml cut-off) in assessment of seizures defined by electroencephalogram (EEG) with history of sustained single or multiple TBI have been demonstrated for children and adult patients indicating a development of ‘chronic’ conditions [13].

Sideline testing of AMPAR peptide and antibody

Recognizing the medical need for sideline testing for mTBI (largely for emergency care), a point-of-care (POC) testing platform has been recently undertaken for AMPAR peptide and antibody assays are being tested in clinical studies (www.drdbiotech.com).

A lateral flow sandwich assay to detect AMPAR Ab consists of a blood filtering sample pad, a pad containing gold nanoshells conjugated to protein A, a nitrocellulose strip with immobilized AMPAR peptide, a control line, and a cellulose absorbent. Applied to the blood filter, erythrocytes are removed from the sample, which passes to the conjugate pad where AMPAR IgGs are captured by protein A. When the complex reaches the peptide test line stripe on nitrocellulose, it binds to the test line yielding a visible signal with intensity proportional to the concentration of the AMPAR Ab presented in the sample (Fig. 2).

The control line then captures a portion of the remaining nanoshells regardless of the presence or absence of the peptide (Fig. 3).

The AMPAR peptide prototype test that works on a similar principle, employed gold nanoparticles as the signal-generating species covalently bound to specific antibodies against AMPAR peptide. This assay captures the AMPAR peptide from the blood sample between two different Abs, one immobilized on the nitrocellulose and the other on the gold nanoshells. This ‘bridging’ of the analyte leads to the immobilization of the particles at the test line producing a colour signal.

Conclusion

The laboratory assessment of concussion at the pitch sideline in competitive contact sports or on the field of combat is required to assist in the objective confirmation of when an injured athlete should return to play or a soldier may return to duty. Accurate diagnosis of concussion and appropriate management of subtle brain injury to prevent damage to the long-term health of athletes and others at risk of re-injury. Specific brain biomarkers detected by a rapid blood test would have important diagnostic/prognostic capabilities, particularly for concussion, to objectively evaluate early signs of further brain-function deterioration and assist in navigating personalized therapy when required. Clinical use of blood tests can reliably detect subtle brain impact, predict consequences and aid in triaging persons with persistent symptoms after a recurrent concussion for diffuse tensor or diffuse-weighted imaging modalities of MRI [17].

Early identification of concussion has the potential to become a key component of a successful treatment strategy and outcome monitoring. Advances in analytical assay technologies have made it possible to develop a rapid, cost-effective test that can be used to target populations and select a risk group for post-traumatic seizures to direct to the immediate attention of a specialist.

The opportunity of using ‘yes/no’ lateral flow tests without a need for an instrumental readout, being simply read by eye, would make a huge difference in supplying coaches with reliable, simple and rapid tests in return-to-play decisions. There is also a high demand for portable POC tests for mTBI diagnosis in military combat and civilian emergency settings.

References

1. Faul M, Xu L, Wald MM, Coronado VG. Traumatic brain injury in the United States. Emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and deaths 2002–2006. Atlanta, GA. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control 2010 (https://www.cdc.gov/traumaticbraininjury/pdf/blue_book.pdf).

2. Klinke T, Daboul A, Maron J, Gredes T, Puls R, Jaghsi A, Biffar R. Artifacts in magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography caused by dental materials. PLoS One 2012; 7: e31766–31771.

3. Napp AE, Enders J, Roehle R, Diederichs G, Rief M, Zimmermann E, Martus P, Dewey M. Analysis and prediction of claustrophobia during MR imaging with the Claustrophobia Questionnaire: an observational prospective 18-month single-center study of 6500 patients. Radiology 2017; 283: 148–157.

4. Dambinova SA. Diagnostic challenges in traumatic brain injury. IVD Technology 2007; 3: 3–7.

5. Dambinova SA. Biomarkers for transient ischemic attack (TIA) and ischemic stroke. Clin Lab Inter 2008; 32: 7–10.

6. Danilenko UD, Khunteev GA, Bagumyan A, Izykenova GA. Neurotoxicity biomarkers in experimental acute and chronic brain injury. In: Dambinova SA, Hayes RL, Wang KKW (editors). Biomarkers for TBI. RSC Publishing, RSC Drug Discovery Series 2012; pp87–98.

7. Gill S, Pulido O. Glutamate receptors in peripheral tissue. In: Gill S, Pulido O (editors). Excitatory transmission outside the CNS. Kluwer Academic Publishers 2010; p3.

8. Hammond JC, McCullumsmith RE, Funk AJ, Haroutunian V, Meador-Woodruff JH. Evidence for abnormal forward trafficking of AMPA receptors in frontal cortex of elderly patients with schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology 2010; 35: 2110–2119.

9. Christensen PC, Samadi-Bahrami Z, Pavlov V, Stys PK, Moore GR. Ionotropic glutamate receptor expression in human white matter. Neurosci Lett 2016; 630: 1–8.

10. Raad M, Nohra E, Chams N, Itani M, Talih F, Mondello S, Kobeissy F. Autoantibodies in traumatic brain injury and central nervous system trauma. Neuroscience 2014; 281: 16–23.

11. Dambinova SA, Shikuev AV, Weissman JD, Mullins JD. AMPAR peptide values in blood of nonathletes and club sport athletes with concussions. Mil Med 2013; 3: 285–290.

12. Dambinova SA, Maroon JC, Sufrinko AM, Mullins JD, Alexandrova EV, Potapov AA. Functional, structural, and neurotoxicity biomarkers in integrative assessment of concussions. Front Neurol 2016; 7: 172.

13. Mullins JD. Biomarkers of TBI: implications for diagnosis and management of contusions. AMSUS 118th Annual Continuing Education Meeting. Seattle, WA, USA 2013; 147. (http://amsusce.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Abstract-Summaries-10.22.13.2.pdf)

14. Dambinova SA, Izykenova GA, Burov SV, Grigorenko EV, Gromov SA. The presence of autoantibodies to N-terminus domain of GluR1 subunit of AMPA receptor in the blood serum of patients with epilepsy. J Neurol Sci 1997; 152: 93–97.

15. Dambinova SA, Granstrem OK, Tourov A, Salluzzo R, Castello F, Izykenova GA. Monitoring of brain spiking activity and autoantibodies to N-terminus domain of GluR1 subunit of AMPA receptors in blood serum of rats with cobalt-induced epilepsy. J Neurochem 1998; 71: 2088–2093.

16. Goryunova AV, Bazarnaya NA, Sorokina EG, Semenova NY, Globa OV, Semenova ZhB, Pinelis VG, Roshal’ LM, Maslova OI. Glutamate receptor antibody concentrations in children with chronic post-traumatic headache. Neurosci Behav Physiol 2007; 37:761–764.

17. Bonow RH, Friedman SD, Perez FA, Ellenbogen RG, Browd SR, MacDonald CL, Vavilala MS, Rivara FP. Prevalence of abnormal magnetic resonance imaging findings in children with persistent symptoms after pediatric sports-related concussion. J Neurotrauma 2017; 34: 1–7.

The authors

Svetlana A Dambinova*1 DSc, PhD; Rozalyn Heath1; Galina A Izykenova2 PhD

1Brain Biomarkers Research Laboratory, DeKalb Medical Center, Decatur, GA, USA

2GRACE Laboratories, LLC, Atlanta, GA, USA

*Corresponding author

E-mail: dambinova@aol.com