Introducing the DxN VERIS molecular diagnostics system from Beckman Coulter, Inc.

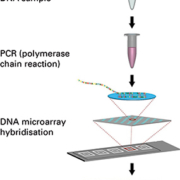

Delegates at ECCMID 2015, held in Copenhagen from 25th to 28th April 2015, attended a symposium introducing Beckman Coulter’s new DxN VERIS Molecular Diagnostics System.* DxN VERIS provides a fully automated sample to result platform with true single sample random access, integrating sample introduction, nucleic acid extraction, reaction setup, real-time PCR amplification, detection and results interpretation into a single system that is set to revolutionize laboratory workflows.

Speakers from four of the 10 DxN VERIS beta study sites shared their experiences and results from comparative evaluations of this new system.

Meeting molecular diagnostic needs

By way of introduction, Hervé Fleury described the molecular diagnostic needs in Europe, where laboratories are becoming fewer and larger, both in the public and private sectors. The number of molecular scientists available for routine tasks is also decreasing, he said, and there is a need for the level of automation, from preanalytics to analytical, that the DxN VERIS will bring.

He then described the DxN VERIS technology, which is able to provide results in approximately 75 minutes for DNA targets and in around 110 minutes for RNA targets, performing in excess of 150 and 100 results in 8 hours for DNA and RNA targets respectively. CE marked DxN VERIS assays for human cytomegalovirus (CMV) and hepatitis B virus (HBV) are already available, in addition to assays for hepatitis C virus (HCV) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). DxN VERIS products in the pipeline include assays for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhea (CT/NG), MRSA (screen), Clostridium difficile, respiratory virus multiplex and human papilloma virus (HPV).

Excellent performance criteria

All four speakers at the ECCMID Symposium described excellent analytical and clinical performance criteria for the VERIS assays evaluated.

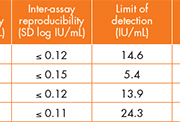

Jacques Izopet reported very good analytical performance results for all four VERIS assays that are currently available (table 1). In addition, these assays demonstrated good agreement with an alternative method (Cobas® Ampliprep/ Cobas® TaqMan™). Significantly, in a patient monitoring setting, the VERIS CMV assay demonstrated overlapping patterns compared to this alternative for plasma samples and compared to a whole blood reference method (figure 1).

Rafael Delgado then went on to present the results from his evaluation of the VERIS CMV and HBV assays. At his laboratory, both assays were extremely sensitive and specific, exhibited a high linearity and repeatability, and showed good correlation with an alternative method (Cobas Ampliprep/ Cobas TaqMan*) (figure 2). In addition, the system demonstrated no carry over when known high positive samples were interspersed among known negative samples.

Rafael Delgado concluded that the overall performance and easy to use design of the DxN VERIS platform facilitated the introduction of this technology in the laboratory and that the DxN VERIS CMV and HBV viral load assays are helpful new solutions for patient management.

In his evaluation of the DxN VERIS HBV assay, Duncan Whittaker observed excellent precision (within and between run), with a standard deviation of ≤ 0.12, and a limit of detection of 7.99 IU/mL, which is less than the manufacturer’s claim of 10 IU/mL. He described the existing method at the Sheffield laboratory as very manual (with separate extraction and amplification systems) which was adequate when they received just 10-12 HBV samples every two weeks but which struggles to cope now that they are receiving up to 80 samples per week.

Duncan Whittaker reported that the quantitative results from the VERIS assay were similar to their exisitng method (Qiagen) (figure 3) with improved precision at lower levels (table 2). He was also able to demonstrate excellent performance and reproducibility across HBV genotypes. In conclusion, he stated that the DxN VERIS Molecular Diagnostics System offers significant improvements in laboratory workflow and time.

Finally, Giovanni Gesu also shared his results from the evaluation of the DxN VERIS HBV assay. At the Niguarda ca’ Granda Hospital in Milan, DxN VERIS HBV demonstrated excellent within and between run precision (SD ≤ 0.156), linearity (1.63 – 8.82 log IU/mL) and sensitivity (limit of detection 6.82 IU/mL), and performed well compared to an alternative HBV real time method (Abbott m2000).

In order to demonstrate the potential workflow and throughput efficiences that the DxN VERIS platform could achieve, Giovanni Gesu applied the throughput capabilities of this new system to a typical day in his laboratory, in which 33 CMV, 17 HBV, 26 HCV and 21 HIV samples were received. With samples arriving at two hour intervals throughout the day between 10am and 4pm, the true single sample random access capability of the DxN VERIS platform combined with assay runtimes of around 70 minutes for DNA tests and around 110 minutes for RNA tests, would mean that samples would not need to be batched and that all results could be reported by 6pm on the same day (figure 4).

Conclusions

In conclusion, each of the speakers at the ECCMID Symposium agreed that the analytical performance of the DxN VERIS assays evaluated was excellent, and they compared well to other molecular diagnostic assays currently available. In addition, the sample-to- result automation and true single sample random access of the DxN VERIS Molecular Diagnostics System offer workflow improvements and laboratory efficiencies.

For further information about the DxN VERIS Molecular Diagnostics System and the DxN VERIS assays currently available, please contact: Tiffany Page, Senior Pan European Marketing Manager Molecular Diagnostics, Email: info@beckmanmolecular.com

*Not for sale or distribution in the U.S.; not available in all markets.

** TaqMan® is a registered trademark of Roche Molecular Systems, Inc. Used under permission and license.

Beckman Coulter, the stylized logo, DxN and VERIS are trademarks of Beckman Coulter, Inc. Beckman Coulter and the stylized logo are registered in the USPTO.