Use of serum free light chain analysis in screening for multiple myeloma in primary care patients

Identification of a serum or urine paraprotein is a key element in the diagnosis of multiple myeloma. Traditionally, this has been achieved using a combination of serum and urine electrophoresis, but this can result in incomplete investigation. The use of serum free light chains as an alternative screening test has been advocated to overcome this.

by David Baulch and Beverley Harris

Multiple myeloma

Multiple myeloma (MM) accounts for 1% of all cancers, with nearly 5000 people in the UK being diagnosed each year. The average age of presentation is 70 with only 15% of patients presenting at less than 60 years of age [1]. Its prevalence has increased by 11% in the last decade, due mainly to increased survival rates in those diagnosed [2]. Despite this, MM still accounts for around 2700 deaths annually in the UK and over 70 000 worldwide with a median survival of only 3–4 years from diagnosis [3].

MM is characterized by the accumulation of clonal plasma cells, predominantly within the bone marrow, and subsequent clonal expansion of the plasma cell lineage [4]. It is almost always preceded by a premalignant, asymptomatic period of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) [1]. The process of immunoglobulin (Ig) production by plasma cells is normally under a state of homeostasis, but random and non-random genetic aberrations, epigenetic changes and atypical interactions within the bone marrow microenvironment can cause uncontrolled proliferation of neoplastic plasma cells, leading to plasma cell disorders (PCDs) such as MM [4]. Clonal expansion of a plasma cell line under such circumstances can cause overproduction of intact monoclonal Ig (IgG, IgA, IgM, rarely IgD and IgE) or monoclonal free light chains (FLCs) kappa and lambda. Although the classification of PCDs is based on the immunoglobulin type secreted, 1–2% of MM cases are classified as non-secretory. This may be due to an absence of secreted monoclonal protein (M protein), or secretion at a concentration below the limits of the laboratory methods used for detection.

Compared with other cancers, diagnosis of MM is challenging. Patients present with a range of non-specific symptoms and as a result often have a string of primary care consultations resulting in diagnostic delay. Such delays significantly impact the clinical course of MM [5], for which a complete cure remains elusive.

Consequences of diagnostic delay

Studies have shown that over 50% of patients attending primary care institutions took 6 months (33% >12 months) from the onset of the first related symptoms to referral [5]. Another study showed the time to diagnosis of MM can be unacceptably prolonged [6] and the pathway to diagnosis in MM was more likely to include a string of repeated primary care consultations, infrequent use of urgent referral routes and increased emergency presentation [7]. In particular, patients whose referral was delayed by 6 months or more were more likely to suffer a greater number of more significant complications such as renal insufficiency which, if swift diagnosis had occurred, may have been reversible [5]. This highlights the need not only to raise awareness of disease symptoms, but to increase the sensitivity of laboratory detection.

Laboratory investigation of multiple myeloma

In addition to clinical and hematological investigations, screening for MM within the laboratory is based on the detection and classification of M proteins by serum protein electrophoresis (the separation of serum proteins according to molecular size, hydrophobicity and electric charge [8]), followed by immunofixation or immunotyping to identify and quantify the Ig isotypes. This method is less reliable for detecting disease when only FLCs are secreted, as these are rapidly cleared by the kidneys. Free light chains in the urine [known as Bence Jones protein (BJP)] can also be detected by electrophoresis followed by immunofixation. However, this methodology is time consuming and may not detect low concentration BJP in dilute urine samples [9]. Interpretation of the results can be difficult and should be performed by appropriately qualified and experienced laboratory staff. In addition, obtaining both urine and serum samples for screening can be problematic, with some laboratories reporting that both samples are received for only ~17% of MM screens.

There is growing evidence to support the direct measurement and quantitation of serum kappa and lambda FLCs in diagnosis, monitoring and prognosis of MM and related PCDs [4]. The serum FLC (sFLC) assay (The Binding Site™) was first developed in 2001 [10]. It is an immunoturbidimetric method using latex-enhanced polyclonal sheep antibodies targeted to epitopes on the light chains of Ig that are exposed when the light chain is ‘free’, i.e. not bound to heavy chain Ig. Results are expressed as a ratio of kappa : lambda light chains.

This sFLC assay can be used to replace traditional urine methods for the laboratory detection of FLCs. This practice has the obvious benefit of using a single serum sample and eliminating the need for a paired urine sample, which may not always be supplied. In addition to the reported increased diagnostic sensitivity of the sFLC assay, an unexpected finding by Dispenzieri et al. was that baseline sFLC results can be used in prognostication and risk stratification of MGUS [11]. Although the rationale for this is poorly understood, it is thought that a greater degree of abnormality in the sFLC ratio reflects an increasing tumour burden.

Studies such as these have informed changes to MM guidelines published in 2016 [12] to acknowledge that significantly abnormal FLC ratios, in the absence of clinical features of end organ damage, can be used in the diagnosis of MM [4]. This eliminates a traditional major challenge with MM diagnosis in that disease definition was clinicopathological. The use of the sFLC ratio in this way therefore marks a milestone in the early detection of MM and highlights a disease transition to being a laboratory-defined rather than a symptom-defined disease, allowing for earlier intervention.

There is, however, controversy as to whether the sFLC assay is indeed a robust candidate for inclusion in PCD screening strategies. There is currently only limited guidance on how it should be used in clinical practice [4] and there is ongoing debate regarding result interpretation, especially for those mildly abnormal ratios. There are, therefore, many considerations to be made before such screening could be implemented.

Study overview and results

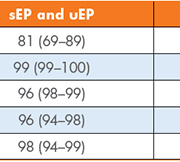

Our real-time prospective study aimed to assess the clinical utility of three index laboratory investigations [serum and urine protein electrophoresis (sEP and uEP) and sFLC] to determine the most effective first-line testing strategy for detecting PCDs in primary care patients. These laboratory investigations were performed on 446 samples with no previous history of, or investigations for, MM. The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV) and efficiency were calculated for our current screening tests (sEP and uEP) and the use of sEP with sFLC as an alternative strategy. Figures 1 and 2 outline the process for each of these screening strategies and a summary of the results is given in Table 1.

Conclusion

The purpose of a medical screening programme is to recognize a disease in its preclinical phase to allow intervention at an earlier stage. Such strategies have benefits, risks and costs and the final screening algorithm is often a compromise between these three. However, a proposed screening strategy should fulfil the criteria outlined by Wilson and Jungner in 1968 [13]. Of note, criterion 4 suggests there should be a detectable preclinical stage, in this case MGUS, and criterion 5 suggests there should be a suitable test for screening strategies. This real-time prospective study presents evidence of the clinical utility of the sFLC assay and its use in developing a more sensitive screening strategy for PCD detection.

Standard screening practice combining sEP and uEP increased the sensitivity of the constituent index tests (78% and 30% respectively) to 81%, meaning the addition of urinalysis to sEP increased the sensitivity by only 3%. This reinforces the need for a more sensitive method for detecting sFLC than sEP alone. This combination also displayed a good PPV without compromising efficiency (98%). Despite this, its use missed significant cases of PCDs including a light-chain multiple myeloma, a possible but unconfirmed (in the time frame of the study) case of MM and 10 cases of MGUS, highlighting its limitation as a first line screening investigation.

Combining sEP with sFLC analysis increased the sensitivity from sEP alone by 20% (data not shown), again suggesting singular sEP testing is not sensitive enough to detect minor abnormalities in FLC production. This proposed combination of screening tests increased sensitivity by 17% when compared with current protocols, indicating that the sFLC assay is more sensitive than urinalysis for detecting PCDs. The sFLC assay has been demonstrated to show a high sensitivity for light chain MM and non-secretory MM [14]. These often present with normal sEP and uEP, especially in low tumour burden stages when renal function remains adequate, which may explain the increased sensitivity of sFLC over uEP.

The results of this study confirm also those of others [15], which show that the addition of sFLC analysis to sEP increases the detection of MM and related PCDs. In our case, there was a 17% increase in patients with a PCD detected. However, a concurrent rise in false positive results (10%) was also seen when compared to traditional screening protocols. Investigation into this was beyond the scope of our study, though the false positive rate could potentially be reduced by employing screening strategies that apply renal reference intervals for the sFLC ratio for those with renal insufficiency.

Summary

On balance, there are several advantages to replacing urinalysis with the sFLC assay. These include increased clinical sensitivity for detection of early-stage disease, patient convenience in submitting a single serum sample rather than two separate specimens, increased use of automation and reduction in subjectivity in reporting of results. However, it is also important to consider the potential increased cost of performing sFLC on all samples submitted for myeloma screening, the importance of using appropriate reference ranges and the need to develop guidelines for interpretation of borderline results. This latter point is particularly important in order that unnecessary referrals are prevented, and should involve close liaison with local hematology teams to ensure that primary care clinicians are given clear guidance for further investigation and referral of their patients.

References

1. Bird JM, Owen RG, D’Sa S, Snowden JA, Pratt G, Ashcroft J, Yong K, Cook G, Feyler S, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of multiple myeloma 2011. Br J Haematol. 2011; 154(1): 32–75.

2. Brenner H, Gondos A, Pulte D. Expected long-term survival of patients diagnosed with multiple myeloma in 2006–2010. Haematologica 2009; 94(2): 270–275.

3. Rajkumar SV, Kyle RA, Therneau TM, Melton LJ, III, Bradwell AR, Clark RJ, Larson DR, Plevak MF, Dispenzieri A, Katzmann JA. Serum free light chain ratio is an independent risk factor for progression in monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. Blood 2005; 106(3): 812–817.

4. Rajkumar SV, Dimopoulos MA, Palumbo A, Blade J, Merlini G, Mateos MV, Kumar S, Hillengass J, Kastritis E, et al. International Myeloma Working Group updated criteria for the diagnosis of multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol. 2014; 15(12): e538–548.

5. Kariyawasan CC, Hughes DA, Jayatillake MM, Mehta AB. Multiple myeloma: causes and consequences of delay in diagnosis. QJM 2007; 100(10): 635–640.

6. Howell DA, Smith AG, Jack A, Patmore R, Macleod U, Mironska E, Roman E. Time-to-diagnosis and symptoms of myeloma, lymphomas and leukaemias: a report from the Haematological Malignancy Research Network. BMC Hematol. 2013; 13(1): 9.

7. Elliss-Brookes L, McPhail S, Ives A, Greenslade M, Shelton J, Hiom S, Richards M. Routes to diagnosis for cancer – determining the patient journey using multiple routine data sets. Br J Cancer 2012; 107(8): 1220–1226.

8. Bossuyt X. Separation of serum proteins by automated capillary zone electrophoresis. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2003; 41(6): 762–772.

9. Kaplan IV, Levinson SS. Misleading urinary protein pattern in a patient with hypogammaglobulinemia: effects of mechanical concentration of urine. Clin Chem. 1999; 45(3): 417–419.

10. Bradwell AR, Carr-Smith HD, Mead GP, Tang LX, Showell PJ, Drayson MT, Drew R. Highly sensitive, automated immunoassay for immunoglobulin free light chains in serum and urine. Clin Chem. 2001; 47(4): 673–680.

11. Dispenzieri A, Kyle R, Merlini G, Miguel JS, Ludwig H, Hajek R, Palumbo A, Jagannath S, Blade J, et al. International Myeloma Working Group guidelines for serum-free light chain analysis in multiple myeloma and related disorders. Leukemia 2009; 23(2): 215–224.

12. Myeloma: diagnosis and monitoring. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) 2016. (https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng35)

13. Wilson JM, Jungner YG. [Principles and practice of mass screening for disease]. Bol Oficina Sanit Panam. 1968; 65(4): 281–393 (in Spanish).

14. Jagannath S. Value of serum free light chain testing for the diagnosis and monitoring of monoclonal gammopathies in hematology. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma 2007; 7(8): 518–523.

15. McTaggart MP, Lindsay J, Kearney EM. Replacing urine protein electrophoresis with serum free light chain analysis as a first-line test for detecting plasma cell disorders offers increased diagnostic accuracy and potential health benefit to patients. Am J Clin Pathol. 2013; 140(6): 890–897.

The authors

David Baulch* MSc, Beverley Harris MSc, FRCPath

Department of Clinical Biochemistry, Royal United Hospitals Bath NHS Foundation Trust, Bath, UK

*Corresponding author

E-mail: david.baulch@nhs.net