The potential of the microbiome for colorectal cancer screening

Alterations of the microbiome are associated with colorectal cancer. Research suggests that microbiome data could improve colorectal cancer screening. Analysis of the microbiome directly from existing screening methods offers the opportunity to rapidly translate this research into practice, with the potential to develop a multifactorial colorectal cancer screening tool.

by Dr Caroline Young and Professor Philip Quirke

Current colorectal cancer screening methods

Different countries have adopted various approaches to colorectal cancer screening. They share a common goal: detection of asymptomatic adenomas or early stage carcinomas, as detection and treatment at an earlier stage is associated with improved survival [1]. Two main screening methods are in use: detection of fecal occult blood and visualization of the colon. Stool DNA testing has recently been approved but is currently prohibitively expensive.

Detection of fecal occult blood can be achieved using the guaiac fecal occult blood test (gFOBT) or an immunochemical method, fecal immunochemical test (FIT). The gFOBT method requires participants to apply stool to a gFOBT card on three occasions and return this to a screening centre through the post. Hydrogen peroxide is applied and if heme is present, blue discolouration occurs. This method has been shown to reduce mortality by 16 % [2]. The FIT method requires participants to insert a FIT probe into stool and return this to a screening centre through the post. An antibody-based assay is used to detect globin. FIT is more sensitive and specific, can be analysed quantitatively and has improved acceptability [3]. Participants in whom fecal occult blood is detected above a threshold, by either method, are referred for colonoscopy.

Alternatively, direct visualization of the colon by colonoscopy/sigmoidoscopy can be undertaken as first-line screening. Limitations include procedural risks, associated costs, workforce capacity and reduced acceptability [4].

The microbiome and colorectal cancer

The microbiome can be characterized using a number of technologies: next generation sequencing (NGS) of bacterial 16SrRNA, whole genome shotgun metagenomics of bacterial communities or the analysis of fecal metabolites (metabolomics). These techniques have enabled an appreciation of the diversity and function of the microbiome in health and disease.

Epidemiological studies demonstrate that the incidence of colorectal cancer is highest in countries with a Western culture, which encompasses Western diet, sanitation and hygiene, medication use, urbanization, etc. [5]. Migrant populations to such countries acquire the increased risk, suggesting an environmental risk factor. African Americans, who typically have a high incidence of colorectal cancer, have been shown to have different microbiomes to Native Africans, who have a low incidence of colorectal cancer [6] and the diets typical of these two groups have been shown to differentially influence the microbiome [7].

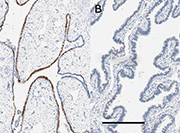

Numerous studies have found differences in the microbiome, ‘dysbiosis’, of patients with colorectal adenomas or carcinomas compared to healthy controls [8]. In general, dysbiosis is characterized by a decrease of short chain fatty acid-producing bacteria, an increase of bacteria that produce bile salts or hydrogen sulphide, an increase of pathogenic bacteria and inflammation [9]. In particular, the species Fusobacterium nucleatum, a Gram-negative oral commensal, has been associated with colorectal carcinoma in many studies.

Animal models have explored potential mechanisms [10] and interestingly show that risk is transferable with transplant of dysbiotic microbiomes. This suggests that dysbiosis may be causative or promotional of the development of colorectal cancer, rather than merely associative.

Given the association between dysbiosis and colorectal cancer, researchers have considered whether the microbiome could be used as a screening tool.

The microbiome compared to gFOBT

Several studies have compared the accuracy of the microbiome as a screening tool to gFOBT. Amiot et al. showed that a screening model combining age plus microbiome (typed by qPCR) was no better than a model combining age plus gFOBT [11]. However, metabolomic analysis [by 1(H)-NMR spectroscopy] was more accurate than gFOBT [12]. Zeller et al. created a screening model that combined metagenomic data with gFOBT results, which lead to an increase in sensitivity compared to gFOBT alone. This model was subsequently validated in a cohort of a different nationality. It showed some ability to distinguish colorectal cancer from a distinct bowel condition (inflammatory bowel disease) and could be extrapolated to NGS of 16SrRNA (a cheaper method) [13].

Zackular et al. used 16SrRNA analysis of the microbiome to create models combining microbiome data and patient metadata that were more accurate than models based on metadata alone [14]. A model comprising BMI, microbiome data and gFOBT was more accurate at distinguishing adenoma from carcinoma than gFOBT alone. Yu et al. used metagenomics to identify two discriminatory bacterial genes that they then validated as biomarkers by qPCR (a cheaper method) in a cohort of a different nationality. The area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve for discriminating carcinoma from controls was 0.84, although gFOBT or FIT screening was not performed for comparison [15].

The microbiome compared to FIT

As FIT is replacing gFOBT in many screening programmes and has a higher sensitivity, comparing the accuracy of the microbiome as a screening tool with FIT is more appropriate.

Baxter et al. used 16SrRNA to create a screening model that combined microbiome data and FIT to discriminate healthy controls from cases with either adenoma or carcinoma [16]. This model was more sensitive but less specific than FIT alone; it detected 70% of cancers and 37% of adenomas which were missed by FIT. Liang et al. [17] identified four bacterial species (one being F. nucleatum) by qPCR that could distinguish colorectal carcinoma from healthy controls with greater accuracy than FIT. Combining microbiome and FIT data afforded greater accuracy still.

Goedert et al. [18] analysed the microbiome by 16SrRNA in patients with a positive FIT result at baseline. The microbiome data gave an area under the ROC curve for discriminating between healthy controls and colorectal adenoma of 0.767.

Limitations of current research

The studies mentioned above show promise for the microbiome as a potential colorectal cancer screening tool. However, they should be interpreted with a degree of caution, owing to a number of limitations which mean that aspects of the studies do not realistically reflect screening conditions. Several of the studies assessed participants at increased risk of colorectal cancer or who were symptomatic. Some collected stool samples following bowel preparation and colonoscopy; one study found that this did not affect the significance of results [16], whereas another found that it did [15]. Several studies included adenomas <10 mm within their control groups. Many of the studies created models that distinguished adenomas from carcinomas or carcinomas from healthy controls; few designed models to discriminate between healthy controls and participants with any colorectal lesion (i.e. either adenoma or carcinoma).

All of the studies used whole stool samples that were refrigerated or frozen by participants at home or delivered within a limited time window to research centres. This method of sample collection would not translate to national screening programmes, which already struggle with poor participant uptake. In light of this, researchers have, therefore, investigated whether the microbiome can be analysed directly from the existing screening tools, gFOBT or FIT.

Analysing the microbiome directly from existing screening tools

Sinha et al. emphasize the need to assess reproducibility, stability over time and how accurately results reflect the gold standard (fresh or immediately frozen stool) when analysing different methods of microbiome sample collection [19]. They found that 16SrRNA microbiome results were similar when analysed from unprocessed or processed gFOBT cards and, in addition to Dominianni et al. [20], showed stability after storage at room temperature for several days. This work was extended by Taylor et al. [21] who demonstrated that the microbiome is stable when analysed by 16SrRNA from processed gFOBT cards stored at room temperature for up to 3 years.

Lotfield et al. showed that metabolomic assessment of the microbiome by ultra-performance liquid chromatography and high resolution/tandem mass spectrometry was stable and accurate (albeit with a degree of bias affecting certain metabolite groups) when analysed directly from gFOBT samples but not from FIT samples [22]. This suggests that different methods of sample collection may be more or less appropriate dependent upon the method of microbiome analysis.

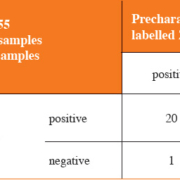

These studies have assessed methods of microbiome sample collection from healthy volunteers. Baxter et al. [23] have analysed the microbiome directly from processed FIT from subjects with normal bowels, colorectal adenomas or carcinomas. Their study comes with the caveat that some of the stool samples were collected after bowel preparation and colonoscopy; samples were stored at −80 °C before being thawed and transferred to FIT; FIT was refrigerated for up to 2 days, processed, then stored at −20 °C before being thawed for microbiome analysis. The study demonstrated that a screening model to discriminate between healthy controls and subjects with any colonic lesion had a similar area under the ROC curve whether microbiome analysis was performed directly from FIT samples or whole stool samples.

As an alternative to stool, Westenbrink et al. analysed microbiome-related volatile organic compounds from urine [24] and described a similar sensitivity for the detection of colorectal cancer as gFOBT or FIT.

Conclusion

Research suggests that there is potential for microbiome analysis to both augment and to be integrated with existing screening methods. The landscape of colorectal cancer screening is changing [25]; it seems likely that a more sophisticated, multifactorial screening tool will be adopted. Microbiome analysis is likely to contribute and may even offer information beyond that of screening, e.g. prevention or treatment targets [26]. Furthermore, collection of longitudinal, population-based microbiome data via national screening programmes will transform the field of microbiome research.

References

1. Cancer Research UK (http://www.cancerresearchuk.org).

2. Hewitson P, Glasziou PP, Irwig L, Towler B, Watson E. Screening for colorectal cancer using the faecal occult blood test, Hemoccult. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007; DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001216.pub2

3. Schreuders EH, Grobbee EJ, Spaander MC, Kuipers EJ. Advances in fecal tests for colorectal cancer screening. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2016; 14(1): 152–162.

4. US Preventive Services Task Force, Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, Davidson KW, Epling JW Jr, García FA, Gillman MW, Harper DM, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA 2016; 315(23): 2564–2575.

5. Haggar FA, Boushey RP. colorectal cancer epidemiology: incidence, mortality, survival, and risk factors. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2009; 22(4): 191–197.

6. Ou J, Carbonero F, Zoetendal EG, DeLany JP, Wang M, Newton K, Gaskins HR, O’Keefe SJ. Diet, microbiota, and microbial metabolites in colon cancer risk in rural Africans and African Americans. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013; 98(1): 111–120.

7. David LA, Maurice CF, Carmody RN, Gootenberg DB, Button JE, Wolfe BE, Ling AV, Devlin AS, Varma Y, et al. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature 2014; 505(7484): 559–563.

8. Borges-Canha M, Portela-Cidade JP, Dinis-Ribeiro M, Leite-Moreira AF, Pimentel- Nunes P. Role of colonic microbiota in colorectal carcinogenesis: a systematic review. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2015; 107(11): 659–671.

9. Sun J, Kato I. Gut microbiota, inflammation and colorectal cancer. Genes Dis. 2016; 3(2): 130–143.

10. Keku TO, Dulal S, Deveaux A, Jovov B, Han X. The gastrointestinal microbiota and colorectal cancer. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2015; 308(5): G351–363.

11. Amiot A, Mansour H, Baumgaertner I, Delchier JC, Tournigand C, Furet JP, Carrau JP, Canoui-Poitrine F, Sobhani I; CRC group of Val De Marne. The detection of the methylated Wif-1 gene is more accurate than a fecal occult blood test for colorectal cancer screening. PLoS One 2014; 9(7): e99233.

12. Amiot A, Dona AC, Wijeyesekera A, Tournigand C, Baumgaertner I, Lebaleur Y, Sobhani I, Holmes E. (1)H NMR spectroscopy of fecal extracts enables detection of advanced colorectal neoplasia. J Prot Res. 2015; 14(9): 3871–3881.

13. Zeller G, Tap J, Voigt AY, Sunagawa S, Kultima JR, Costea PI, Amiot A, Böhm J, Brunetti F, et al. Potential of fecal microbiota for early-stage detection of colorectal cancer. Mol Syst Biol. 2014; 10: 766.

14. Zackular JP, Rogers MA, Ruffin MT 4th, Schloss PD. The human gut microbiome as a screening tool for colorectal cancer. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2014; 7(11): 1112–1121.

15. Yu J, Feng Q, Wong SH, Zhang D, yi Liang Q, Qin Y, et al. Metagenomic analysis of faecal microbiome as a tool towards targeted non-invasive biomarkers for colorectal cancer. Gut 2015; DOI: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309800.

16. Baxter NT, Ruffin MT 4th, Rogers MA, Schloss PD. Microbiota-based model improves the sensitivity of fecal immunochemical test for detecting colonic lesions. Genome Med. 2016; 8(1): 37.

17. Liang JQ, Chiu J, Chen Y, Huang Y, Higashimori A, Fang JY, Brim H, Ashktorab H, Ng SC, et al. Fecal bacteria act as novel biomarkers for non-invasive diagnosis of colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2016; DOI: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-1599.

18. Goedert JJ, Gong Y, Hua X, Zhong H, He Y, Peng P, Yu G, Wang W, Ravel J, et al. Fecal microbiota characteristics of patients with colorectal adenoma detected by screening: a population-based study. EBioMedicine 2015; 2(6): 597–603.

19. Sinha R, Chen J, Amir A, Vogtmann E, Shi J, Inman KS, Flores R, Sampson J, Knight R, Chia N. Collecting fecal samples for microbiome analyses in epidemiology studies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016; 25(2): 407–416.

20. Dominianni C, Wu J, Hayes RB, Ahn J. Comparison of methods for fecal microbiome biospecimen collection. BMC Microbiol. 2014; 14: 103.

21. Taylor M, Wood H, Halloran S, Quirke P. Examining the potential use and long term stability of guaiac faecal occult blood test cards for microbial DNA 16srRNA sequencing. J Clin Pathol. Accepted for publication.

22. Loftfield E, Vogtmann E, Sampson JN, Moore SC, Nelson H, Knight R, Chia N, Sinha R. Comparison of collection methods for fecal samples for discovery metabolomics in epidemiologic studies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016; 25(11): 1483–1490.

23. Baxter NT, Koumpouras CC, Rogers MA, Ruffin MT 4th, Schloss P. DNA from fecal immunochemical test can replace stool for microbiota-based colorectal cancer screening. Microbiome 2016; 4(1): 59.

24. Westenbrink E, Arasaradnam RP, O’Connell N, Bailey C, Nwokolo C, Bardhan KD, Covington JA. Development and application of a new electronic nose instrument for the detection of colorectal cancer. Biosens Bioelectron. 2015; 67: 733–738.

25. Nguyen MT, Weinberg DS. Biomarkers in colorectal cancer screening. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2016; 14(8): 1033–1040.

26. Pitt JM, Vetizou M, Waldschmitt N, Kraemer G, Chamaillard M, Boneca IG, Zitvogel L. Fine-tuning cancer immunotherapy: optimizing the gut microbiome. Cancer Research 2016; 76(16): 4602–4607.

The authors

Caroline Young* MA, BMBCh; Philip Quirke BM, PhD, FRCPath, FMedSci

Wellcome Trust Brenner Building, St James University Hospital, Leeds LS9 7TF, UK

*Corresponding author

E-mail: caroline.young4@nhs.net